Why do we take mental shortcuts?

Heuristics

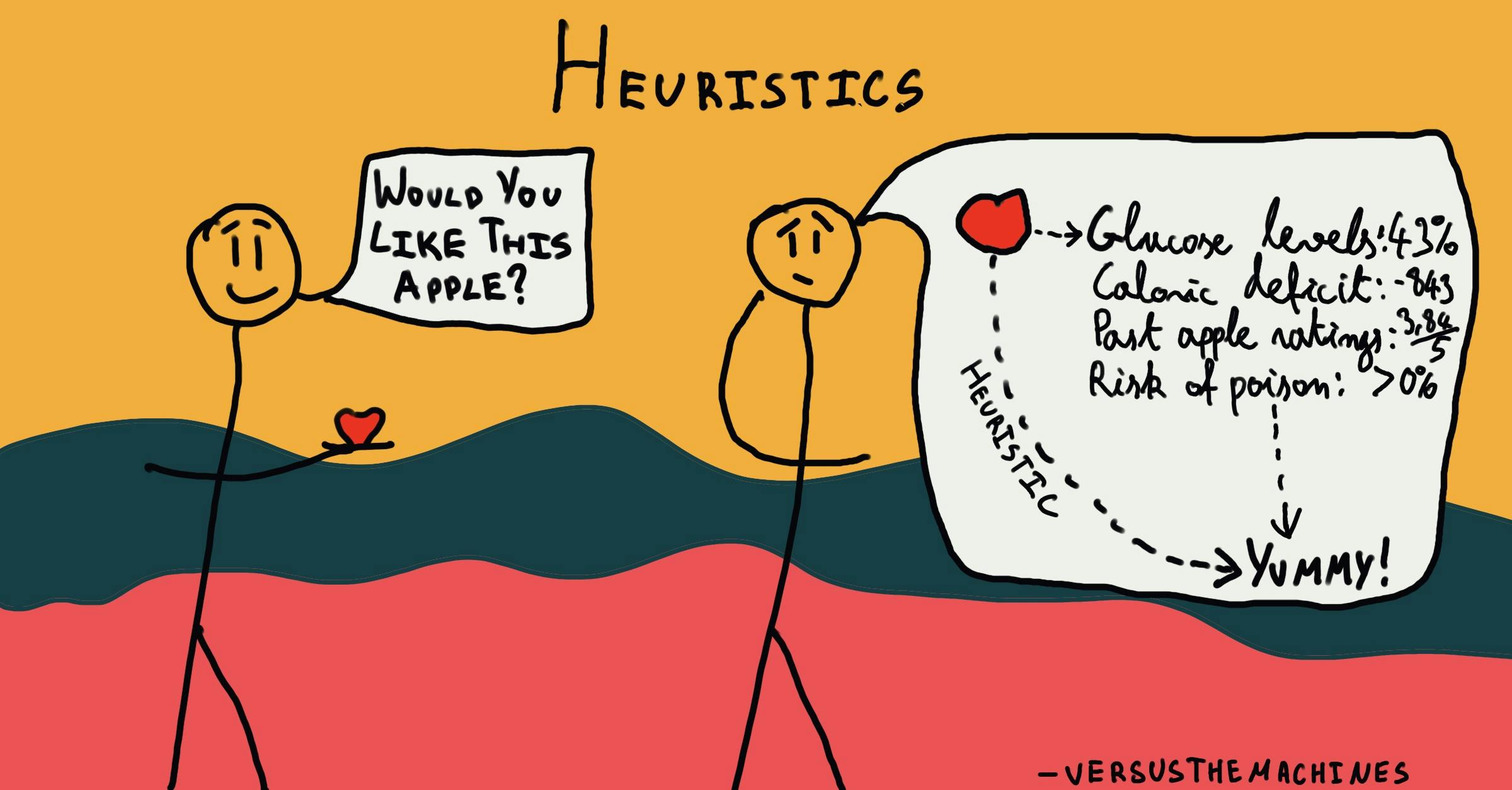

, explained.What are Heuristics?

Heuristics are mental shortcuts that can facilitate problem-solving and probability judgments. These strategies are generalizations, or rules-of-thumb, that reduce cognitive load. They can be effective for making immediate judgments, however, they often result in irrational or inaccurate conclusions.

Where this bias occurs

We use heuristics in all sorts of situations. One type of heuristic, the availability heuristic, often happens when we’re attempting to judge the frequency with which a certain event occurs. Say, for example, someone asked you whether more tornadoes occur in Kansas or Nebraska. Most of us can easily call to mind an example of a tornado in Kansas: the tornado that whisked Dorothy Gale off to Oz in Frank L. Baum’s The Wizard of Oz. Although it’s fictional, this example comes to us easily. On the other hand, most people have a lot of trouble calling to mind an example of a tornado in Nebraska. This leads us to believe that tornadoes are more common in Kansas than in Nebraska. However, the states actually report similar levels.1

Debias Your Organization

Most of us work & live in environments that aren’t optimized for solid decision-making. We work with organizations of all kinds to identify sources of cognitive bias & develop tailored solutions.

Individual effects

The thing about heuristics is that they aren’t always wrong. As generalizations, there are many situations where they can yield accurate predictions or result in good decision-making. However, even if the outcome is favorable, it was not achieved through logical means. When we use heuristics, we risk ignoring important information and overvaluing what is less relevant. There’s no guarantee that using heuristics will work out and, even if it does, we’ll be making the decision for the wrong reason. Instead of basing it on reason, our behavior is resulting from a mental shortcut with no real rationale to support it.

Systemic effects

Heuristics become more concerning when applied to politics, academia, and economics. We may all resort to heuristics from time to time, something that is true even of members of important institutions who are tasked with making large, influential decisions. It is necessary for these figures to have a comprehensive understanding of the biases and heuristics that can affect our behavior, so as to promote accuracy on their part.

How it affects product

Heuristics can be useful in product design. Specifically, because heuristics are intuitive to us, they can be applied to create a more user-friendly experience and one that is more valuable to the customer. For example, color psychology is a phenomenon explaining how our experiences with different colors and color families can prime certain emotions or behaviors. Taking advantage of the representativeness heuristic, one could choose to use passive colors (blue or green) or more active colors (red, yellow, orange) depending on the goals of the application or product.18 For example, if a developer is trying to evoke a feeling of calm for their app that provides guided meditations, they may choose to make the primary colors of the program light blues and greens. Colors like red and orange are more emotionally energizing and may be useful in settings like gyms or crossfit programs.

By integrating heuristics into products we can enhance the user experience. If an application, device, or item includes features that make it feel intuitive, easy to navigate and familiar, customers will be more inclined to continue to use it and recommend it to others. Appealing to those mental shortcuts we can minimize the chances of user error or frustration with a product that is overly complicated.

Heuristics and AI

Artificial intelligence and machine learning tools already use the power of heuristics to inform its output. In a nutshell, simple AI tools operate based on a set of built in rules and sometimes heuristics! These are encoded within the system thus aiding in decision-making and the presentation of learning material. Heuristic algorithms can be used to solve advanced computational problems, providing efficient and approximate solutions. Like in humans, the use of heuristics can result in error, and thus must be used with caution. However, machine learning tools and AI can be useful in supporting human decision-making, especially when clouded by emotion, bias or irrationality due to our own susceptibility to heuristics.

Why it happens

In their paper “Judgment Under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases”2, Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky identified three different kinds of heuristics: availability, representativeness, as well as anchoring and adjustment. Each type of heuristic is used for the purpose of reducing the mental effort needed to make a decision, but they occur in different contexts.

Availability heuristic

The availability heuristic, as defined by Kahneman and Tversky, is the mental shortcut used for making frequency or probability judgments based on “the ease with which instances or occurrences can be brought to mind”.3 This was touched upon in the previous example, judging the frequency with which tornadoes occur in Kansas relative to Nebraska.3

The availability heuristic occurs because certain memories come to mind more easily than others. In Kahneman and Tversky’s example participants were asked if more words in the English language start with the letter K or have K as the third letter Interestingly, most participants responded with the former when in actuality, it is the latter that is true. The idea being that it is much more difficult to think of words that have K as the third letter than it is to think of words that start with K.4 In this case, words that begin with K are more readily available to us than words with the K as the third letter.

Representativeness heuristic

Individuals tend to classify events into categories, which, as illustrated by Kahneman and Tversky, can result in our use of the representativeness heuristic. When we use this heuristic, we categorize events or objects based on how they relate to instances we are already familiar with. Essentially, we have built our own categories, which we use to make predictions about novel situations or people.5 For example, if someone we meet in one of our university lectures looks and acts like what we believe to be a stereotypical medical student, we may judge the probability that they are studying medicine as highly likely, even without any hard evidence to support that assumption.

The representativeness heuristic is associated with prototype theory.6 This prominent theory in cognitive science, the prototype theory explains object and identity recognition. It suggests that we categorize different objects and identities in our memory. For example, we may have a category for chairs, a category for fish, a category for books, and so on. Prototype theory posits that we develop prototypical examples for these categories by averaging every example of a given category we encounter. As such, our prototype of a chair should be the most average example of a chair possible, based on our experience with that object. This process aids in object identification because we compare every object we encounter against the prototypes stored in our memory. The more the object resembles the prototype, the more confident we are that it belongs in that category.

Prototype theory may give rise to the representativeness heuristic as it is in situations when a particular object or event is viewed as similar to the prototype stored in our memory, which leads us to classify the object or event into the category represented by that prototype. To go back to the previous example, if your peer closely resembles your prototypical example of a med student, you may place them into that category based on the prototype theory of object and identity recognition. This, however, causes you to commit the representativeness heuristic.

Anchoring and adjustment heuristic

Another heuristic put forth by Kahneman and Tversky in their initial paper is the anchoring and adjustment heuristic.7 This heuristic describes how, when estimating a certain value, we tend to give an initial value, then adjust it by increasing or decreasing our estimation. However, we often get stuck on that initial value – which is referred to as anchoring – this results in us making insufficient adjustments. Thus, the adjusted value is biased in favor of the initial value we have anchored to.

In an example of the anchoring and adjustment heuristic, Kahneman and Tversky gave participants questions such as “estimate the number of African countries in the United Nations (UN).” A wheel labeled with numbers from 0-100 was spun, and participants were asked to say whether or not the number the wheel landed on was higher or lower than their answer to the question. Then, participants were asked to estimate the number of African countries in the UN, independent from the number they had spun. Regardless, Kahneman and Tversky found that participants tended to anchor onto the random number obtained by spinning the wheel. The results showed that when the number obtained by spinning the wheel was 10, the median estimate given by participants was 25, while, when the number obtained from the wheel was 65, participants’ median estimate was 45.8.

A 2006 study by Epley and Gilovich, “The Anchoring and Adjustment Heuristic: Why the Adjustments are Insufficient”9 investigated the causes of this heuristic. They illustrated that anchoring often occurs because the new information that we anchor to is more accessible than other information Furthermore, they provided empirical evidence to demonstrate that our adjustments tend to be insufficient because they require significant mental effort, which we are not always motivated to dedicate to the task. They also found that providing incentives for accuracy led participants to make more sufficient adjustments. So, this particular heuristic generally occurs when there is no real incentive to provide an accurate response.

Quick and easy

Though different in their explanations, these three types of heuristics allow us to respond automatically without much effortful thought. They provide an immediate response and do not use up much of our mental energy, which allows us to dedicate mental resources to other matters that may be more pressing. In that way, heuristics are efficient, which is a big reason why we continue to use them. That being said, we should be mindful of how much we rely on them because there is no guarantee of their accuracy.

Why it is important

As illustrated by Tversky and Kahneman, using heuristics can cause us to engage in various cognitive biases and commit certain fallacies.10 As a result, we may make poor decisions, as well as inaccurate judgments and predictions. Awareness of heuristics can aid us in avoiding them, which will ultimately lead us to engage in more adaptive behaviors.

How to avoid it

Heuristics arise from automatic System 1 thinking. It is a common misconception that errors in judgment can be avoided by relying exclusively on System 2 thinking. However, as pointed out by Kahneman, neither System 2 nor System 1 are infallible.11 While System 1 can result in relying on heuristics leading to certain biases, System 2 can give rise to other biases, such as the confirmation bias.12 In truth, Systems 1 and 2 complement each other, and using them together can lead to more rational decision-making. That is, we shouldn’t make judgments automatically, without a second thought, but we shouldn’t overthink things to the point where we’re looking for specific evidence to support our stance. Thus, heuristics can be avoided by making judgments more effortfully, but in doing so, we should attempt not to overanalyze the situation.

How it all started

The first three heuristics – availability, representativeness, as well as anchoring and adjustment – were identified by Tverksy and Kahneman in their 1974 paper, “Judgment Under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases”.13 In addition to presenting these heuristics and their relevant experiments, they listed the respective biases each can lead to.

For instance, upon defining the availability heuristic, they demonstrated how it may lead to illusory correlation, which is the erroneous belief that two events frequently co-occur. Kahneman and Tversky made the connection by illustrating how the availability heuristic can cause us to over- or under-estimate the frequency with which certain events occur. This may result in drawing correlations between variables when in reality there are none.

Referring to our tendency to overestimate our accuracy making probability judgments, Kahneman and Tversky also discussed how the illusion of validity is facilitated by the representativeness heuristic. The more representative an object or event is, the more confident we feel in predicting certain outcomes. The illusion of validity, as it works with the representativeness heuristic, can be demonstrated by our assumptions of others based on past experiences. If you have only ever had good experiences with people from Canada, you will be inclined to judge most Canadians as pleasant. In reality, your small sample size cannot account for the whole population. Representativeness is not the only factor in determining the probability of an outcome or event, meaning we should not be as confident in our predictive abilities.

Example 1 – Advertising

Those in the field of advertising should have a working understanding of heuristics as consumers often rely on these shortcuts when making decisions about purchases. One heuristic that frequently comes into play in the realm of advertising is the scarcity heuristic. When assessing the value of something, we often fall back on this heuristic, leading us to believe that the rarity or exclusiveness of an object contributes to its value.

A 2011 study by Praveen Aggarwal, Sung Yul Jun, and Jong Ho Huh evaluated the impact of “scarcity messages” on consumer behavior. They found that both “limited quantity” and “limited time” advertisements influence consumers’ intentions to purchase, but “limited quantity” messages are more effective. This explains why people get so excited over the one-day-only Black Friday sales, and why the countdowns of units available on home shopping television frequently lead to impulse buys.14

Knowledge of the scarcity heuristic can help businesses thrive, as “limited quantity” messages make potential consumers competitive and increase their intentions to purchase.15 This marketing technique can be a useful tool for bolstering sales and bringing attention to your business.

Example 2 – Stereotypes

One of the downfalls of heuristics is that they have the potential to lead to stereotyping, which is often harmful. Kahneman and Tversky illustrated how the representativeness heuristic might result in the propagation of stereotypes. The researchers presented participants with a personality sketch of a fictional man named Steve followed by a list of possible occupations. Participants were tasked with ranking the likelihood of each occupation being Steve’s. Since the personality sketch described Steve as shy, helpful, introverted, and organized, participants tended to indicate that it was probable that he was a librarian.16 In this particular case the stereotype is less harmful than many others, however it accurately illustrates the link between heuristics and stereotypes.

Published in 1989, Patricia Devine’s paper “Stereotypes and Prejudice: Their Automatic and Controlled Components” illustrates how, even among people who are low in prejudice, rejecting stereotypes requires a certain level of motivation and cognitive capacity.17 We typically use heuristics in order to avoid exerting too much mental energy, specifically when we are not sufficiently motivated to dedicate mental resources to the task at hand. Thus, when we lack the mental capacity to make a judgment or decision effortfully, we may rely upon automatic heuristic responses and, in doing so, risk propagating stereotypes.

Stereotypes are an example of how heuristics can go wrong. Broad generalizations do not always apply, and their continued use can have serious consequences. This underscores the importance of effortful judgment and decision-making, as opposed to automatic.

Summary

What it is

Heuristics are mental shortcuts that allow us to make quick judgment calls based on generalizations or rules of thumb.

Why it happens

Heuristics, in general, occur because they are efficient ways of responding when we are faced with problems or decisions. They come about automatically, allowing us to allocate our mental energy elsewhere. Specific heuristics occur in different contexts; the availability heuristic happens because we remember certain memories better than others, the representativeness heuristic can be explained by prototype theory, and the anchoring and adjustment heuristic occurs due to lack of incentive to put in the effort required for sufficient adjustment.

Example 1 – Advertising

The scarcity heuristic, which refers to how we value items more when they are limited, can be used to the advantage of businesses looking to increase sales. Research has shown that advertising objects as “limited quantity” increases consumers' competitiveness and their intentions to buy the item.

Example 2 – Stereotypes

While heuristics can be useful, we should exert caution, as they are generalizations that may lead us to propagate stereotypes ranging from inaccurate to harmful.

How to avoid it

Putting more effort into decision-making instead of making decisions automatically can help us avoid heuristics. Doing so requires more mental resources, but it will lead to more rational choices.

Related TDL articles

What are Heuristics

This interview with The Decision Lab’s Managing Director Sekoul Krastev delves into the history of heuristics, their applications in the real world, and their consequences, both positive and negative.

10 Decision-Making Errors that Hold Us Back at Work

In this article, Dr. Melina Moleskis examines the common decision-making errors that occur in the workplace. Everything from taking in feedback provided by customers to cracking the problems of on-the-fly decision-making, Dr. Moleskis delivers workable solutions that anyone can implement.