Why do we better remember items at the beginning or end of a list?

The Serial Position Effect

, explained.What is the Serial Position Effect?

The serial position effect describes how our memory is affected by the position of information in a sequence. It suggests that we best remember the first and last items in a series and find it hard to remember the middle items.

Where this bias occurs

The serial position effect impacts memory recall most obviously for lists. Imagine that your partner calls you to ask you to pick up some food at the grocery store on your way home. They ask you to get bananas, apples, bread, chicken, white rice, broccoli, and crackers.

When you get to the grocery store, you can’t remember everything that your partner listed. You only recall that they wanted you to get bananas, apples, broccoli, and crackers.

In this scenario, the serial position effect has impacted your memory. You can only think of the first and last couple of items on your partner’s list, but not the items in the middle.

Debias Your Organization

Most of us work & live in environments that aren’t optimized for solid decision-making. We work with organizations of all kinds to identify sources of cognitive bias & develop tailored solutions.

Related Biases

Individual effects

Not being able to remember all of the items on our grocery list isn’t the end of the world. After all, we can easily write down what food we need to buy so that we can reference it again, instead of relying solely on our memory.

However, what happens when we need to remember information that we only briefly encounter and can’t go back to? For example, imagine you are in a lecture, and your professor is providing some important definitions. You try to jot down his explanations, but he is speaking quite quickly. As you go to write the last phrase he spoke, you realize you only remember the first few words and the last few words, but not the whole sentence.

The serial position effect means that your memory is hindered by the information presented in the middle of a series. We need to be aware of how our memory prioritizes so we can organize information in a manner most optimal for recall. For instance, if the items most essential in a list happen to be in the middle, we can move them to the front to guarantee we will remember them. Unfortunately, tactics like repeating a list in the same order, again and again, are usually not enough to commit all of the items to memory.

Systemic effects

Although we can use tactics to counter how the serial position effect causes us to forget items in the middle of a series, we are often not able to control how information is originally presented to us. It is usually up to people in leadership positions to decide how to present important information. This lack of control we experience begins all the way in childhood, such as when teachers plan their classes.

Teachers often have to try and squeeze large amounts of information into just a few classes and hope that their students can absorb it all. This makes awareness of the serial position effect vital for effective teaching. Teachers should plan lessons in a way that takes advantage of the arrangement of information because cognitive biases are hard to overcome even when students are aware of them. By presenting the key takeaways at the beginning or end of class, students have the best chance of remembering those most important aspects.

How it affects product

The Interaction Design Foundation (IDF) has suggested different ways we can consider the serial effect position in user interface design to help consumers access and retain information. The first suggestion is only to include task-relevant application information to avoid overwhelming users. Incorporating tools that guide users helps them encode small bits of information at a time. Of course, presenting important information first or last on an interface guarantees users will store these items in their memory.7

Another suggestion put forward by the IDF is to limit the amount of information that users may need to recall – since the recency effect demonstrates we can only store small amounts of information in our short-term memory. We often browse interfaces too quickly to commit information to our long-term memory. For example, when designing a clothing website, designers can allow users to activate filters so they only view a small number of clothing items instead of the entire stock. This organization ensures users can remember the items they like and help them decide what to purchase more seamlessly.7

The serial position effect and AI

Just as with products, the order in which machine learning generates outputs affects what pieces of information we encode and store in our memory. This is especially true since language model AI often formats responses as bullet point lists to help enhance comprehensibility for users. However, this design feature may perpetuate the serial position effect even further.

For example, imagine you’re brainstorming research paper topics using ChatGPT, which provides you with a list of seven options. You are much more likely to remember and select one of the first or last ideas, even if the most engaging prompt was somewhere in the middle of the list.

Why it happens

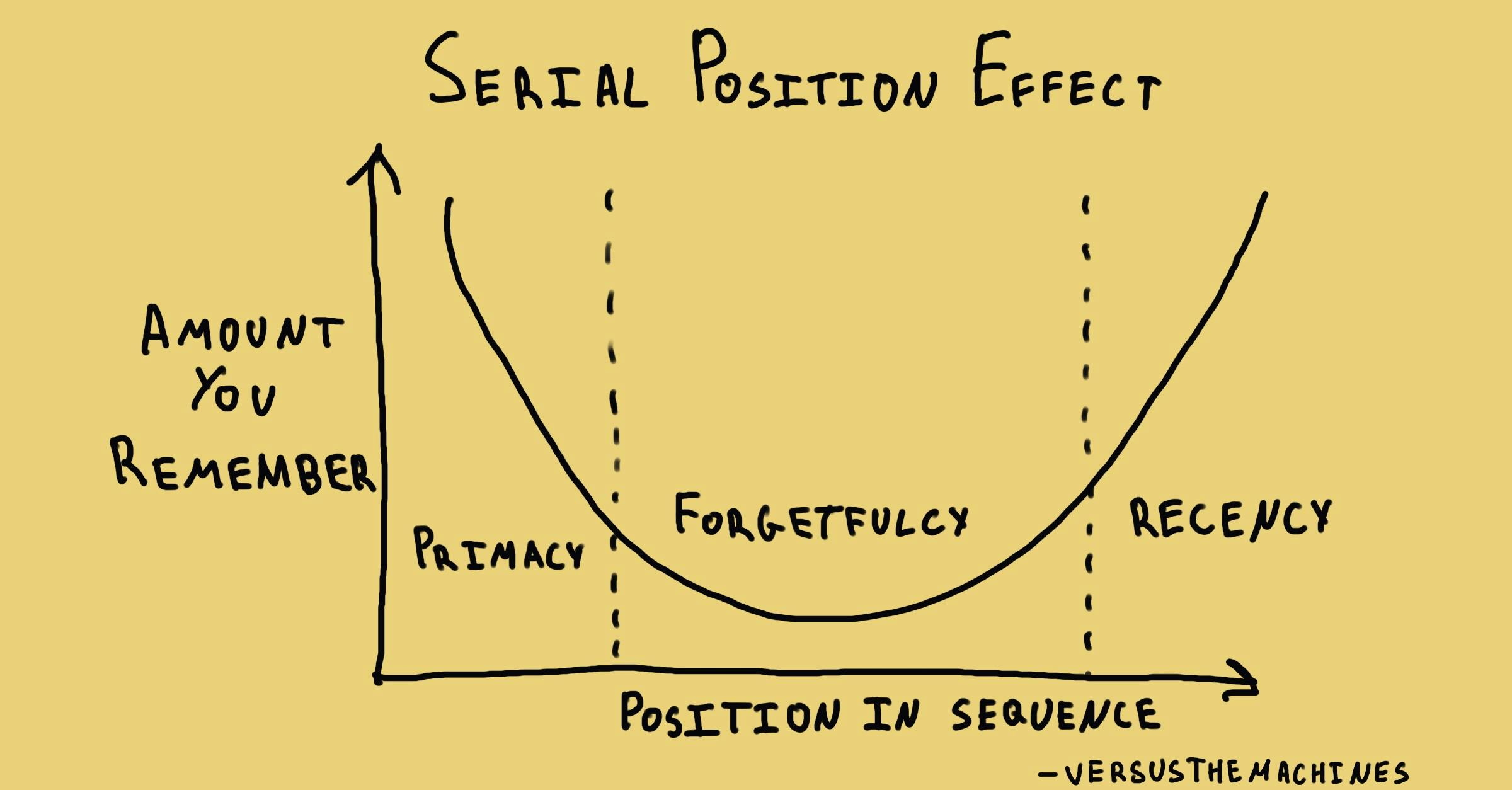

The serial position effect is caused by two other memory recall biases called the primacy effect and the recency effect.

The primacy effect describes our tendency to better remember information at the beginning of a series. We store these items in our long-term memory more easily because it takes less processing power for our brains to remember individual items. As a series continues, our brains have to process groups of items, making the subsequent information harder to remember.1

The recency effect describes our tendency to better remember the information we most recently learned, which are typically the items at the end of a series. Unlike the primacy effect, researchers believe the recency effect occurs because we store these items in our short-term memory, which can only hold a small amount of information. This means we can quickly access only the last few items during recall.2

When combined, the primacy effect and the recency effect mean that our memory recall is better for both the items at the beginning and end of a series. Things in the middle of a series are harder to remember because they are no longer in our short-term memory, but we haven’t processed them long enough to store them in our long-term memory.

The serial position effect, therefore, provides evidence for the multi-store model of memory which suggests that information passes from a sensory register into our short-term memory, before ending in our long-term memory.3

Why it is important

Every day we must remember the information presented to us, often formatted in series. This can include remembering a grocery list, memorizing a phone number, or following instructions. Since we want to remember important information, we need to be aware of how our memory works to improve recall.

Moreover, the serial position effect impacts more than day-to-day memory recall. It also influences how we reflect on the past. We may only remember the beginning and end of the event but be unsure about the details in the middle. This becomes an issue in situations like witness testimonies. If we don’t have a complete picture of the sequence of events, we might be left speculating how we got from the beginning to the end of the incident.

Since the serial position effect has both small and large implications on our lives, we must understand how it affects our memories to devise strategies to help counter the fact that it’s harder to remember information in the middle of a series.

How to avoid it

The serial position effect negatively impacts our ability to remember information in the middle of a series. While writing down lists or series of information means that we don’t have to rely on memory for information recall, that is not always practical.

Awareness of the serial position effect can help us decide how to organize information. This can be information that we are presenting to others to help them encode it, or it can be information that we are studying ourselves to make us more likely to recall it when needed. One way to use the serial position effect is to put the most important information at the beginning and end of a series. Another technique could be mixing up the serial position of items.

For example, imagine that you are trying to remember five facts about a particular phenomenon for an exam. Instead of repeatedly studying the five facts in the same order, you might want to write them down in a different order the second time you go through them. That means that different items will be at the beginning, middle, and end of the series. This rearrangement gives you a better chance of remembering more items since more of them will have held a place at the beginning and end.

How it all started

The serial position effect was first coined by German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus in 1885 after conducting a series of memory experiments using himself as his test subject.4 Ebbinghaus was a renowned pioneer in memory, also responsible for discovering the spacing effect.5

In his book Memory: A Contribution to Experimental Psychology, Ebbinghaus outlines a series of free-recall experiments that he conducted on himself to examine whether the position of an item in a list affects how well it is remembered.5 He listened to recordings that he had previously taped of himself saying lists of random syllables like “DAX” and then tried to remember as many as possible. Ebbinghaus found that he could more easily remember the words that were at the beginning and end of the list compared to the words in the middle of the list.

Quickly Ebbinghaus realized that the position of an item in a list did impact how well he could remember it, naming this cognitive bias the serial position effect. He was also the first to suggest that the serial position effect occurs because of a combination of the primacy and recency effects.5

Example 1 – Bilingualism

Most of the studies providing evidence of the serial position effect have been conducted on monolingual speakers. Jeewon Yoo and Margarita Kaushanskaya, two PhD students with an interest in language and memory, wanted to examine whether bilingual individuals experienced the serial position effect in each language to the same degree.6 They were particularly interested in bilingual individuals because they wanted to see if extensive linguistic knowledge countered the serial position effect.

Yoo and Kaushanskaya tested the serial position effect on 20 participants who were fluent in both Korean and English, with Korean being their native or primary language. Participants were presented with lists of 10, 15, and 20 items in both Korean and English and then were asked to recall as many words as possible, in no particular order.

Yoo and Kaushanskaya found that bilingual individuals were similarly impacted by the serial position effect in both their primary (Korean) and secondary (English) languages. However, participants were better able to remember words at the beginning and middle of the list in their native language than in their secondary language. This suggests that the primacy effect was stronger when participants had greater linguistic knowledge. However, the recency effect was not stronger for either of the two languages.6

From these findings, Yoo and Kaushanskaya concluded that linguistic knowledge is not enough to overcome the serial position effect. However, greater mastery over a language can help individuals remember more items at the beginning and middle of a list by tapping into the primacy effect. This slightly reduces the serial position effect since we can remember more items at the beginning of a list.

Example 2 – Restaurant menus

Many companies take advantage of the serial position effect to influence which items customers purchase, especially in the food industry. For example, a restaurant may list all of its most expensive options or its signature dish at the top of the menu. These will leave a lasting first impression on your mind, increasing your chances that you will order them later on. Meanwhile, restaurants may showcase their special desserts and coffees at the end of the menu. Since these are the last items we encode, we might be more likely to recall them when our server asks us if we want anything sweet to eat at the end of our meal.

Summary

What it is

The serial position effect describes our tendency to remember information that is at the beginning or end of a series, but find it harder to recall information in the middle of the series.

Why it happens

The serial position effect occurs because of a combination of the primacy effect and the recency effect. The primary effect makes it easier to remember items at the beginning of a list because it gets stored in our long-term memory. The recency effect makes it easier to remember items at the end of a list because they get stored in our short-term memory.

Example 1 – Linguistic knowledge and the serial position effect

Bilingual speakers show the serial position effect in both their primary and their secondary language, suggesting that better linguistic knowledge does not help completely overcome the serial position effect. However, bilingual speakers experience the primacy effect more when recalling in their native language, remembering more items at the beginning and middle of a list than in their secondary language. Linguistic knowledge helps expand the primacy effect, which in turn reduces the serial position effect.

Example 2 – Restaurant Menus

Restaurants strategically place food items that they want customers to purchase at the beginning and ends of menus to increase the likelihood we will remember them when we order.

How to avoid it

We should try to be aware of the serial position effect to optimize how we ingest information. That can include positioning important information at the beginning and end of a list or switching up the order of items so that each has a better chance of being remembered.

Related TDL articles

Does the Quantified-Self Lead to Behavior Change?

In this article, Zoe Adams examines how health and well-being technology is only useful if we learn how to best navigate and refine the large amounts of data. The quantified-self refers to self-knowledge, and Adams explores how we can make that self-knowledge positively impact behavior. Adams reminds readers of the serial position effect in designing applications for health and well-being, as such memory biases need to be taken into account for the most positive outcomes.

Why do we only remember the first things on our grocery list?

The serial position effect is partially caused by the primacy effect, where we tend to remember the first piece of information we encounter better than the rest. This is because this information is much more likely to be stored in our long-term memory than items we encounter later on. Read this article to learn more about how the primacy effect might impact your memory outside of the serial position effect.