TDL Brief: The Real Drivers of Voter Behavior

As I’m writing this on October 30, 2020, all eyes are on the US election next week.

This is already shaping up to be a historic election, at least in terms of voter turnout. Even five days out from the election, Texas’ early voting surpassed 2016’s total turnout, and nationally, more than 80 million early votes have been cast. This record-breaking early voting pace, accounting for more than 58 percent of the total 2016 turnout, points to the substantial success of numerous “get out the vote” initiatives.

And this is something that should be celebrated. Historically, the US hasn’t been very impressive when it comes to voter turnout. In 2016, only 55.7% of the voting-age population voted. In fact, of all developed countries, US voter turnout ranks 31 out of 35.

But, behind any seemingly successful policy or intervention lurks potentially unforeseen and unintended consequences. As the high turnout of this election is rightly celebrated, it is our job as behavioral scientists to dig deeper in an effort to better understand how these “get out the vote” campaigns may unintentionally bias voter behavior.

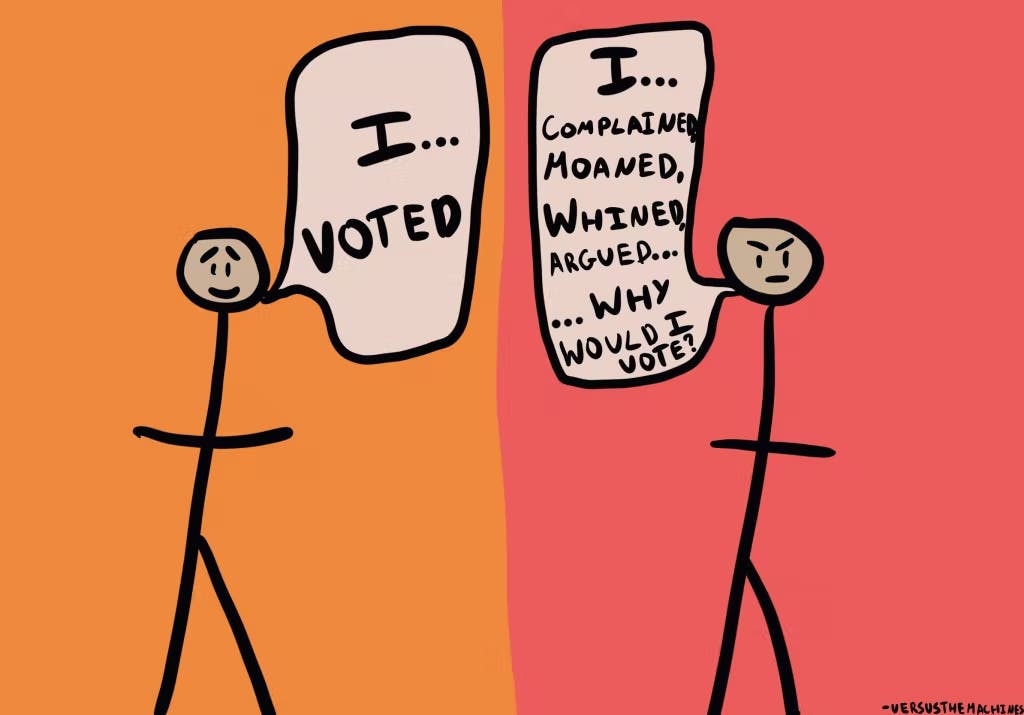

For example, in his article “Is a Biased Vote Better Than No Vote?” TDL contributor Sanketh Andhavarapu highlighted that only encouraging citizens to vote, without also educating them on how to become more politically aware, may lead to voters to rely too heavily on cognitive shortcuts such as the status quo bias or the bandwagon effect.

Understanding the real drivers of voter behavior is clearly critical. So, with the 2020 US presidential election around the corner, TDL gathers some outside perspectives on what drives voter beliefs, turnout, and behavior at the ballot box.

Tom Spiegler, TDL Managing Director

Behavioral Science, Democratized

We make 35,000 decisions each day, often in environments that aren’t conducive to making sound choices.

At TDL, we work with organizations in the public and private sectors—from new startups, to governments, to established players like the Gates Foundation—to debias decision-making and create better outcomes for everyone.

1. What influences voters changes as the election nears.

By: Association for Psychological Science, Who Influences Your Vote? It May Depend on How Soon the Election Is (August 2012)

Political campaigns try to influence public opinion in a multitude of ways—TV ads, lawn signs, word of mouth, to name a few methods. And these efforts to persuade have varying rates of success. But research shows that how successful a given method of persuasion is—say, lawn signs—actually depends on how far away the election is.

When the election is next year, rather than next week, voters are more likely to be persuaded by what the majority of their group thinks about a particular candidate. In other words, when the decision of who to vote for is distant and abstract, opinions of peer groups carry a lot of weight. This means that polls declaring, for example, “70% of citizens trust X candidate on the economy” can carry a lot of weight.

Closer to the election, though, it’s a different story. At this point in the election cycle, a voter is more likely to be influenced by individual opinions than by group consensus. For example, seeing a neighbor’s lawn sign or having a conversation with a trusted friend now has an outsized impact when compared with a TV ad highlighting state-wide polling.

2. Are you someone who votes?

By: Scientific American, How Science Can Help Get Out the Vote (September 2016)

One way to increase voter turnout is to capitalize on people’s desire to shape or conform to a worthy self-identity—the identity of “someone who votes.”

A 2011 study presented potential voters with two separate questions. One of the questions was framed in terms of identity (“How important is it to you to be a voter?”) and the other was framed in terms of an activity (“How important is it to you to vote?”).

Would-be voters that were presented with the self-identity question turned out at significantly higher rates in real-world elections: the 2008 presidential election in California and the 2009 gubernatorial election.

Getting citizens to embrace “being a voter” as part of their identity can therefore be an effective tool for governments seeking to boost voter participation.

3. Want to know who will win the election? Focus on citizen unhappiness.

By: MIT Sloan School of Management, Why do people vote the way they do? Unhappiness, says MIT Sloan behavioral scientist, outweighs all other factors (September 2020)

Predicting election results has turned into a multi-billion dollar industry. Analysts look at everything from income levels to unemployment rates, population age, and racial makeup. However, research shows that subjective well-being might be the most robust predictor of electoral success.

For example, in the 2016 U.S. election, counties where voters expressed low levels of overall life satisfaction were strongly associated with an increase in Trump’s vote share, above and beyond what a Republican candidate in a given jurisdiction would ordinarily receive.

The takeaway, which is deceptively simple, is that unhappy people vote against the status quo.

4. Moral beliefs or political affiliation—what comes first?

By: The Atlantic, What Your Politics Do to Your Morals (September 2019)

Every year, a growing number of people instinctively lunge toward one side of the ballot when election time comes around. One of the factors thought to influence a voter’s political leanings is their fundamental moral beliefs. A voter who values patriotism and respect for the troops might look at the party platforms, see that the conservatives are more pro-military, and therefore be more likely to identify as conservative.

But what if it’s the other way around? What if voters purport to care so much about loyalty and the troops because they first identified as conservative?

There is some evidence to suggest this might be the case. And if this is true, it could suggest something a little terrifying for society: that people often make their judgments of right and wrong fit with whatever party they already support. Decades of research on cognitive dissonance shows us that this is hardly beyond the pale.

Politicians fight to convince voters that their vision for America is the correct—and often more moral—one, but what if voters don’t actually care? Perhaps people just pick their team, and force the rest to fall into place.

About the Authors

Dan Pilat

Dan is a Co-Founder and Managing Director at The Decision Lab. He is a bestselling author of Intention - a book he wrote with Wiley on the mindful application of behavioral science in organizations. Dan has a background in organizational decision making, with a BComm in Decision & Information Systems from McGill University. He has worked on enterprise-level behavioral architecture at TD Securities and BMO Capital Markets, where he advised management on the implementation of systems processing billions of dollars per week. Driven by an appetite for the latest in technology, Dan created a course on business intelligence and lectured at McGill University, and has applied behavioral science to topics such as augmented and virtual reality.

Dr. Sekoul Krastev

Sekoul is a Co-Founder and Managing Director at The Decision Lab. He is a bestselling author of Intention - a book he wrote with Wiley on the mindful application of behavioral science in organizations. A decision scientist with a PhD in Decision Neuroscience from McGill University, Sekoul's work has been featured in peer-reviewed journals and has been presented at conferences around the world. Sekoul previously advised management on innovation and engagement strategy at The Boston Consulting Group as well as on online media strategy at Google. He has a deep interest in the applications of behavioral science to new technology and has published on these topics in places such as the Huffington Post and Strategy & Business.