Habits, Happiness, and Personality Types: Gretchen Rubin

Sometimes people will say to me, “Well, which tendency is the happiest, or the healthiest, or the most productive, or the most creative or the most successful.” And what you see is not that one tendency is the best, it’s that certain people have a tendency to figure out how to harness the strengths of the tendency and really take advantage of it. And also learn how to offset the limitations and weaknesses of that tendency so that they manage to get themselves where they want to go. So for obligers, many obligers are wildly successful. Oprah Winfrey’s an obliger, Tiger Woods is an obliger, Daenerys Targaryen is an obliger, Jon Snow’s an obliger.

Intro

In today’s episode of The Decision Corner, we are joined by Gretchen Rubin, a writer, speaker, and influencer on the subjects of happiness, habits, and human nature. Gretchen Rubin is the author of several books, including the number one New York Times bestseller, The Happiness Project. Her books have sold over 3.5 million copies and been published in more than thirty languages globally.

Gretchen has spoken at places such as GE, Google, LinkedIn, Accenture, Facebook, Procter & Gamble, Yale Law School, Harvard Business School, and Wharton as well as at conferences such as SXSW, World Domination Summit, the Atlantic, Alt Design, and Behance’s 99u.

Gretchen graduated from Yale University with a BA in English in 1989 and a J.D in 1994, where she served as the Editor-in-chief of the Yale Law Journal. Some of her specialties include habits, happiness, positive psychology, writing, memoirs, blogging, social media, self-improvement, self-help, non-fiction, and podcasts.

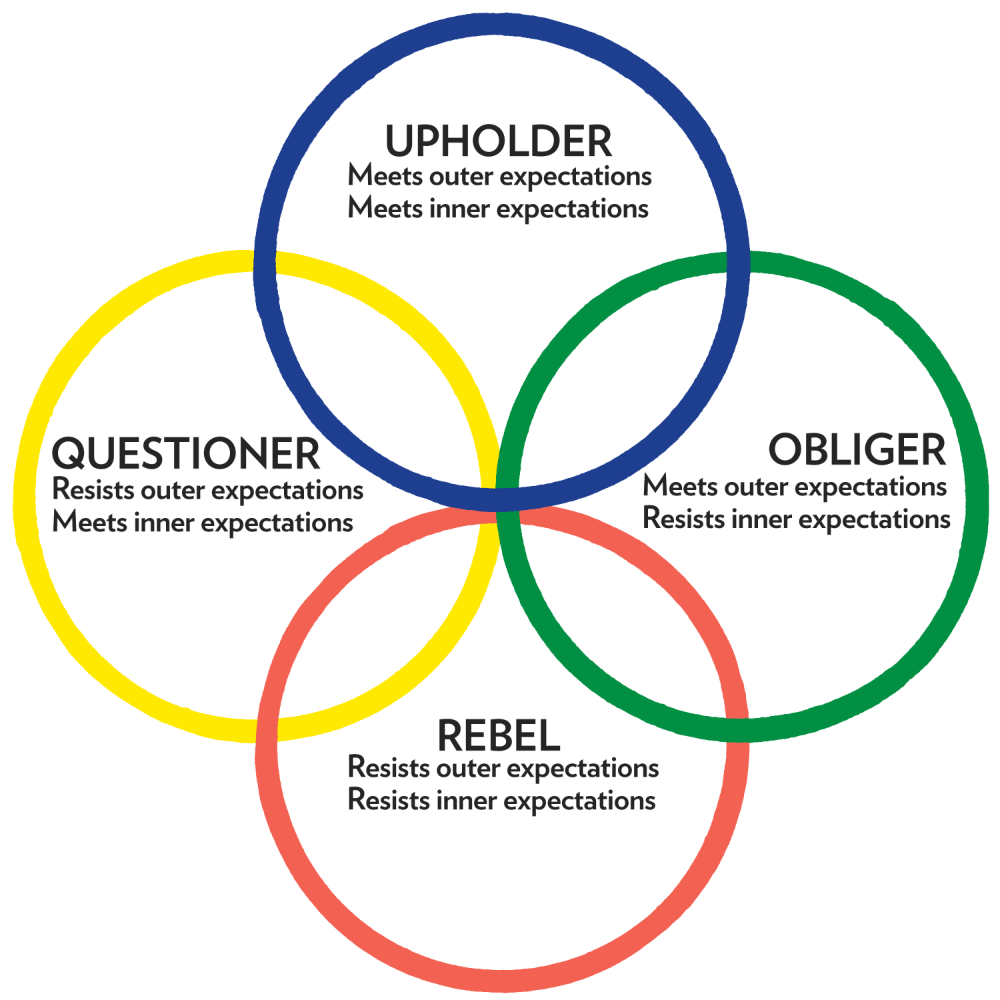

Her “Four Tendencies” personality framework divides people into Upholders, Questioners, Obligers, and Rebels, which will both be routinely mentioned throughout this episode. You can take the quick, free quiz here.

In this episode, we discuss:

- The four tendencies and their respective idiosyncrasies

- The validity of psychological frameworks and when they can be useful

- How to communicate with people more effectively so that they follow through with important behaviors

- What kinds of problems are best suited for the four tendency taxonomy

- Individual versus gender-based differences in behavior

- Public service messages that work for all four tendencies

- The brilliance of the Don’t mess with Texas campaign

- Leveraging big data to test messaging with different tendencies

The conversation continues

TDL is a socially conscious consulting firm. Our mission is to translate insights from behavioral research into practical, scalable solutions—ones that create better outcomes for everyone.

Key Quotes

The four tendencies in Gretchen’s framework

“I realized that at the heart of it was this idea of expectations, how people respond to expectations (which sounds super boring, but it’s very, very juicy) because it turns out we all face two kinds of expectations: outer expectations, like a work deadline or request from a friend, or inner expectations, my own desire to keep a new year’s resolution, my own desire to get back into meditation. And depending on how you respond to outer and inner expectations, that’s what makes you an upholder, a questioner, an obliger, or a rebel. And those are the four tendencies of my framework: upholder, questioner, obliger, and rebel.”

Patterns in how we successfully make or fail to make habits

“And as I was studying habits, I started to notice very, very striking patterns in how people successfully made or failed to make habits, as well as people’s attitudes towards habits. In studying habits, I would often ask people, “How do you feel about new year’s resolutions?” There’s a certain group of people that would always answer the same way; they’d say “Well, I would keep a resolution when it made sense to me, but I would not wait for January 1st because January 1st is an arbitrary date.””

The effectiveness of certain frameworks

“So I think some frameworks try to paint too broad a picture, and you’re sort of like, “Well, this sort of fits but this doesn’t, and it’s kind of fuzzy.” This framework explains just one very narrow aspect of your nature, but it turns out to be very significant. And the way that I’ve seen that most people find it to be useful is that it can eliminate frustration, and conflict, and procrastination, and it can make it more efficient to figure out how to move forward, because you understand what buttons to push.”

Accountability for the four tendencies

“Providing accountability is burdensome. So maybe I don’t want to force everybody into that, also rebels will resist it, but it’s something maybe people could opt into. Some people realize they do better with accountability, but a lot of people don’t really need it. As an upholder, I don’t really need it. Questioners often don’t really need it. Sometimes people like it, so you could let them opt in or opt out. And with a rebel, you always want to make sure that you give the feeling of freedom and choice as much as you can, and maybe, it’s like, “This is our proposed schedule, but if you want to do it another way, let us know, because if you’ve got the chops to pull it off, that can be great too.” (Of course, it’s true that everybody likes a feeling of autonomy, we all like that.)”

Two types of obligers

“So, for instance, you could imagine someone being like, “Oh, I’m an obliger, I never meet my promises to anybody else, I can’t put myself first, I don’t have any self-esteem, I never make myself a priority.” Somebody else is like, “You know what? I give 110% to my clients. You think I’ve got time to exercise? You think I got time to eat right? No way, I don’t have any time to do that kind of stuff because I am 110% for my clients! Look on my wall, there’s a picture of me, my wife is delivering our baby, and I’m on the phone with the client because I give everything to my clients.” They’re both 100% obliger; that is obliger talk. ‘I don’t have time for myself and my own expectations because I’m giving everything to an outer expectation.’ But one person thinks, ‘Oh, I’m so great, this is my best foot forward.’ And the other one thinks, ‘This is a problem, this is a limitation, this is a fault.’ They’re describing the same pattern of behavior.”

Gendered versus individual explanations of behaviour

“My own view is that individual differences swamp gender differences. And I think it’s very easy for people to say, ‘Everybody does this, women do this, men do that.’ And in my observation, in some ways I’m a very typical ‘woman,’ in some ways I’m very atypical. I look at someone like my husband. In some ways, he’s very, very typically ‘male,’ in many ways, he’s not typically male. I think a lot of times these things are not tied to gender–but it is interesting how culture can teach you how to frame your tendency in a different way.”

Gretchen's Work

- Gretchen’s vast array of books

- Gretchen’s other podcast episodes

- Can You Change Your Habits? An Interview with Gretchen Rubin (Interview)

- A Question I’m Often Asked: “How Can We Encourage People to Vote by Applying the Four Tendencies?” (Article)

- To Be Happier, Write Your Own Set of Personal Commandments. (Article)

Transcript

Brooke: Hello everyone and welcome to the Podcast of the Decision Lab, a socially conscious applied research firm that uses behavioral science to improve outcomes for all of society. My name is Brooke Struck, research director at TDL, and I’ll be your host for the discussion. My guest today is Gretchen Rubin, bestselling author, and podcaster, and an expert on happiness. In today’s episode, we’ll be talking about personality types. There are a lot of different taxonomies out there, a lot of different types of types, it’s a huge landscape and we’ll get a lesson from Gretchen and how to navigate those landscapes. Gretchen, thanks for joining us.

Gretchen: I’m so happy to be talking to you.

Brooke: So this happiness project that you’ve been working on, you articulated kind of four tendencies that you saw emerging from the evidence base that you were collecting. Tell us a little bit about that, what are these four tendencies.

Gretchen: I wrote a book called The Happiness Project about how to be happier, and that led me to the study of habits, because what I realized is that often people know what would make them happier. They know they’d be happier if they slept more, exercised more regularly, or read more books, or saw their friends more often, it’s not that they haven’t identified it, but they haven’t made it into a regular habit. A lot of these things, like exercise, you need to do as a habit. And so that led me to the study of habits, which was my book Better Than Before about how we make and break our habits.

Gretchen: And as I was studying habits, I started to notice very, very striking patterns in how people successfully made or failed to make habits, people’s attitudes towards habits. I would often ask people ‘How do you feel about new year’s resolutions?’ and there’s a certain group of people that would always answer the same way. They’d say “Well, I would keep a resolution when it made sense to me, but I would not wait for January 1st, because January 1st is an arbitrary date.”

Gretchen: And that caught my attention because the arbitrariness of January 1st never really bothered me, but clearly it did for these people–they all use that word arbitrary. But my big insight into the four tendencies came into, my sister calls me a happiness bully and I will really prod people about what they are doing to be happier. And a friend said something that struck me like a lightning bolt; I’m sure you’ve heard people say something similar. She said, “It’s weird. I know I’m happier when I exercise. And when I was in high school, I was on the track team and I never missed track practice so why can’t I go running now?” And I thought, “Well, why not?” It’s the same person. It’s the same behavior. At one time, it was effortless, now she can’t do it. How do you explain that? I could generate many ideas about why that might be, but what was really at the heart of it.

Gretchen: And so I was seeing all these patterns and finally, I realized that at the heart of it was this idea of expectations, how people respond to expectations, which sounds super boring, but it’s very, very juicy because it turns out we all face two kinds of expectations, outer expectations, like a work deadline or request from a friend, or inner expectations, my own desire to keep a new year’s resolution, my own desire to get back into meditation. And depending on how you respond to outer and inner expectations, that’s what makes you an upholder, a questioner, an obliger, or a rebel. And those are the four tendencies of my framework, upholder, questioner, obliger, and rebel.

Brooke: Let’s unpack that a little bit. You’ve got to kind of every taxonomizer’s favourite thing, you’ve got a two by two matrix.

Gretchen: No, it’s not a two by two. And that’s really important because for a long time, I was really stuck on the two by two and it doesn’t work as a two by two. What you should envision is a Venn diagram of four overlapping circles in a diamond shape. Each tendency overlaps with two tendencies, they interlock. So there’s kind of a continuum that goes in a circle. So they’re sort of embedded in each other. So it’s not a two by two, getting from the two by two to the Venn diagram was like six months of sweat pouring down my face of intellectual work. But yeah, you get it, it’s four types.

Brooke: Let’s talk about the dimensions here, so you mentioned that you’ve got these four overlapping circles, how is each of the circles defined?

Gretchen: I’ll explain it. Honestly, these are so obvious that most people know what they are right away just from my description and they can do themselves and they can do the people in their lives. And I can tell you the Game of Thrones characters, but if you want to take a quiz, if you go to quiz.gretchenrubin.com, it’s a free, quick quiz, like three million people have taken this quiz and it will give you an answer, some people like to take a quiz and get a report, quiz.gretchenrubin.com, but I’ll just explain it right now, and most people know what they are. So upholder, questioner, obliger, rebel.

Gretchen: Upholders readily meet outer and inner expectations. They meet the work deadline, they keep the new year’s resolution without that much fuss. They want to know what other people expect from them, and that’s important to them, but their expectations for themselves are just as important. So their motto is “discipline is my freedom.”

Gretchen: Then there are questioners, who question all expectations. They’ll do something if they think it makes sense. They really need to see justification, efficiency, reasons, rationale. So if something meets their standard, it meets their inner expectation, they will meet it no problem. If it fails their inner standard, they will resist. So their motto is “I’ll comply if you convince me why.”

Gretchen: Then there are obligers.Obligers readily meet outer expectations, but they struggle to meet inner expectations. And this explained to my friend on the track team. When she had a team and a coach expecting her to show up, she had no trouble, but she was trying to go on her own, it was a challenge. Anytime someone talks about self-care, anytime somebody says, “I keep my promises to other people. Why can’t I keep my promises to myself?” When people say, “Why do I always put others first? I need to work on my motivation.” These statements are big, big signs that a person is an obliger.

Gretchen: The important thing to understand if you’re an obliger, or you’re dealing with an obliger, is that to meet inner expectations, an obliger must have a system of outer accountability. If you want to read more, join a book group. Do you want to exercise more? Work out with a trainer, work out with a friend who’ll be annoyed if you don’t show up, raise money for a charity, take your dog for running who be so disappointed and he will tear up the furniture if he doesn’t go for his run. You need that outer accountability, because obligers are good at following through for other people, but they struggle to follow through for themselves. So their motto is, “you can count on me and I’m counting on you to count on me.”

Gretchen: And then, finally, rebels. Rebels resist all expectations, outer and inner alike. They want to do what they want to do, in their own way, in their own time. They can do anything they want to do, anything they choose to do, but if you ask or tell them to do something, they are very likely to push back. And typically, they don’t like to tell themselves what to do. They won’t sign up for a 10:00 AM spin class on Saturday because they think, “I don’t know what I want to do on Saturday, and just the idea that somebody is expecting me to show up at 10:00 AM is annoying to me.” So their motto is, “you can’t make me and neither can I.” So these are the big four.

Brooke: As I was doing some background reading and digging into these, I really felt kind of called out, I got cornered into my questioner box. Especially when I read, there was one thing that you had written about that questioners can… despite the fact that we love reasons and everything needs to be justified, sometimes when we are pressed to give reasons, we get frustrated.

Gretchen: Questioners often don’t like to be questioned, this is deeply ironic. I’m married to a questioner so I’ve experienced the frustration of this kind of phenomenon firsthand. Do you experience that? Not all questioners have that, but some very strongly do.

Brooke: I totally feel that impulse. It’s not that I don’t like to have my judgments questioned, there are obviously reasons for me to do this. I’m just not the kind of person who would do anything without reasons. So to ask what those reasons are is to suggest that they’re not already there.

Gretchen: Yes, and you’ve done the work and it’s like, “Why are you even expecting me to go through this again?” It is really funny and it’s very helpful, actually, if you’re dealing with a questioner to realize that–because it is true that the other tendencies sometimes get frustrated with this. When I realized this about my husband, it made it less personal, because I used to think, “Are you just jerking my chain to annoy me?” Or, “What does this mean about our relationship that you won’t just answer a simple question?” But now I know this is just a thing that a lot of questioners have. I don’t have to take it personally. I might be annoyed by it, but now I’m just, well, there’s a lot of benefits to being with a questioner and this is one of the downsides.. it helps me have empathy for him and just say, “This is just a thing.”

Brooke: I like the direction that this has taken because I’m curious about the utility of these taxonomies. As I mentioned in my introduction, there are about a million taxonomies out there and they range in kind of the strength of their evidential base and their credibility from the Myers-Briggs test, which has been around for a million years and there’s a huge evidence-base under that, everything to something completely at the opposite end of the spectrum, which is the, ‘which avenger are you’ that you’ll find on Facebook?

Gretchen: Yes, I just read a quiz that was, “how do you eat an Oreo and what it reveals about your inner psychic landscape?” And it was, if you eat this way, you’re repressed or whatever. I was like, “Okay, 10 ways to eat an Oreo, I did not know that it revealed deep aspects of my person.” But it was fun.

Brooke: And that’s interesting, there are a lot of those kinds of quizzes that we’ll take just for fun and we don’t have any greater expectations of them. But I think that some taxonomies, and I would include yours among those, we set higher expectations or loftier goals for ourselves with this, that when we develop these kinds of taxonomies and when we apply them in professional contexts, there’s some work that we want them to do. So what are the kinds of outcomes that people might be seeking when they are trying to select a taxonomy and trying to navigate that landscape?

Gretchen: Well, that is a great question. And what I really love about my framework, if I say so myself, is that it’s very, very specific. So I think some frameworks try to paint too broad a picture, and you’re sort of like, “Well, this sort of fits but this doesn’t, and it’s kind of fuzzy.” This is explaining just one very narrow aspect of your nature but it turns out to be very significant. And the way that I’ve seen that most people find it to be useful is that it can eliminate frustration, and conflict, and procrastination, it can make it more efficient to figure out how to move forward, because you understand what buttons to push.

Gretchen: So for instance, let’s say, I’m having a meeting. I’m the manager and I want everybody to use this new software program. Everybody needs to switch over. So if I know that I have some questioners and some people who aren’t questioners, I might stand up at the meeting and say… (and you’ve probably been there as a questioner where your hand is still up and everybody else’s rolling their eyes and being like, “Why are we still talking about this?” And you’re like, “I don’t understand why people are lemmings and go along with this stuff because it makes no sense.”)

Gretchen: So if I’m the manager, what I can do to manage different people is to say, “Here’s a little presentation to explain to you why corporate has decided we should switch. If you feel that you’ve heard enough to satisfy your understanding of what we’re doing and the plan forward, please feel free to return to your desk. If you have further questions for me to understand why we feel like this is the most efficient decision for our company, I’m happy to stay here for as long as you want to talk about it.”

Gretchen: So now, you’ve kind of divided the audience into people, the questioners, who really want that question to be answered. And then the other people who are like, “This is your job, corporate, to figure out the software, I’ve got other stuff to do.” Or maybe you’re experiencing a conflict in a relationship like, I’m a parent and I have a child who’s very, very smart and clearly can do all kinds of work but just won’t do it. And I set up a star chart, and I set up rewards and punishments, and I try to get the kid motivated. The more I drill down, the worse it gets, and why is that? Well, because I’m doing everything exactly wrong out of the deepest love. I’m just doing everything wrong because I’m being the kind of parent and doing the kinds of things that might’ve worked for me as a child, but I have a rebel child, and I need to think about the rebel tendency, and how to get that rebel child to want to do what I think that child should want to do, like practice a piano, or do homework, or do the soccer drills, or whatever it is.

Gretchen: And so, I think when people see this, it’s either, I can’t get myself to do what I want myself to do, which is very frustrating, or I can’t get other people to do what I want them to do, which is also frustrating. And this often helps explain why those differences are there. Because often what we do is we say what would work for us. So for instance, I’m an upholder and I would say to people things, “Look, I don’t want to be your babysitter, do your own work in your own way. I don’t care how you get there, just get there.” This is not helpful for an obliger. That’s not being a good coworker. Because that’s what works for me, but it’s not going to work for an obliger.

Gretchen: And so, I think that’s what most people use it, is trying to understand, moving forward, how can we have less conflict, more compassion, less procrastination? Also, doctors and healthcare workers want to use the framework a lot. “I tell people to take their blood pressure medication and they just don’t. How can I communicate with them more effectively so that they follow through, put things for their own health?” I hear a lot from people in healthcare.

Brooke: So it sounds like there are two kinds of functions that are emerging from this, and if I can pick up on the healthcare analogy, one is kind of this diagnostic function. I want to understand why someone is behaving the way that they are.

Gretchen: Exactly, yes, because if we understand why we can target our response to be effective instead of just throwing a bunch of spaghetti against the wall.

Brooke: Yeah, so that would be the second component, the more kind of, “I’m going to write the prescription components down. But I’ve diagnosed why this is happening and that helps me to understand the person that I’m interacting with.” As you mentioned in your example before with your husband, it can help you to kind of channel your responses in a different direction that you don’t take it personally, that you understand this is just kind of a feature of their personality. And then, the second component that you move into, which is more of the prescriptive component of what can I do to intervene differently in this ecosystem with these individuals to achieve different results in terms of their behavior or their habits? That kind of thing.

Gretchen: And it’s really important to know these differences, because what works very well with one tendency could actually be counterproductive with another tendency. I think one of the mistakes people make is they’re like, “Well, what’s the best way? What’s the right way? What’s the most efficient way?” Well, there is no one right way, there is no one best way, because people are very different. And so, we have to think about how messages can be delivered and received so that they will be understood and acted upon rather than trying to say like, “Well, if I just give you more and more research, clearly you’re going to be more and more persuaded by that.” And have you noticed? That doesn’t work for a lot of people. I’m not saying it shouldn’t work, I’m just saying it doesn’t work.

Brooke: You brought up an institutional or a kind of organizational example before where you’re explaining some new initiative. You cut loose the people who are ready to be cut loose, but you also leave space open for those who are still seeking to be convinced. And I think that that’s a good illustration of a practical step that we can take to acknowledge that there is no one best way and that we work in professional contexts of diversity of personality types, notwithstanding the fact that we tend to have these self-selection biases where we surround ourselves with people who are just like us, but let’s put that aside. At scale though, what are some of the ways that we can apply the types of insights that you’ve been talking about? And the example that you mentioned is a great one to our workplace contexts where we’ve got lots of people and we have a diversity of personality types, but we also probably need to have… there can’t be an enormous amount of personalization once we get beyond a certain number of people, so how do we cope with that tension?

Gretchen: Well, one of the things I think is just to think about all the four different viewpoints and trying to build that in so that everybody gets what they want. So let’s say you have an initiative that you’re trying to unfold, anything you do, any curriculum you have, any app you have, any approach you have is going to work for some people because basically, anything works for upholders. So they give you this false positive because you’re like, “Oh, 19% of the people had done it, it worked.” You’re like, “Yeah, because anything works for those guys, it’s not that your system is so great.” But then you think, “Okay, I need to get the data, I need to get the research, the reasons for someone. Maybe I’m going to put that on the website, maybe I’m going to have a handout that people can take if they want, I’m not going to bombard everybody with it, but I’m going to have it available for the people who are looking for it, I’m going to make sure that that aspect of whatever I’m proposing feels very available.” Then is there some kind of aspect of accountability? And so, maybe this is for everyone.

Gretchen: A lot of times, workplaces, by their nature, create accountability because there’s deliverables, and deadlines, and teams, and benchmarks, and things like that. But maybe I need to have more immediate accountability, or maybe I want to ask people, “Would you like to have a check in every week?” Some people might say, “I would love that.” I had a friend when she was applying for a position, she would say, “I need a tough boss. I do my best work with a tough boss. Are you a tough demanding boss? Because that’s what I want.” So you might say, “Oh, do you want to have more milestones? Do you want to have… Maybe six months feels too far away for you, maybe you feel like you’d stay on track better if we checked in every week or every month, I’m available.”

Gretchen: Now, providing accountability is burdensome. So maybe I don’t want to force everybody into that, also rebels will resist it, but it’s something maybe people could opt into. A lot of times people realize they do better with accountability, but a lot of people don’t really need it. As an upholder, I don’t really need it. Questioners often don’t really need it. Sometimes people like it, so you could let them opt in or opt out. And then with a rebel, you always want to make sure that you give the feeling of freedom and choice as much as you can, and maybe, it’s sort of like, “This is our proposed schedule, but if you want to do it another way, let us know, because if you’ve got the chops to pull it off, that can be great too.” (Everybody likes a feeling of autonomy, of course, we all like that.)

Gretchen: But for rebels, they tend to do much better job when they don’t feel micromanaged, when they don’t feel like somebody’s looking over their shoulder, when they do feel like they have a lot of flexibility about doing their own work in their own way, and you want to build that. Or if you see that somebody’s not on your program, maybe you want to allow for that flexibility, even unofficially. One of the things that’s interesting about rebels is many rebels are attracted to entrepreneurship or sales, where it’s kind of like Wild Wild West feeling, but some rebels are very attracted to the military, the clergy, the police, large corporations with lots of rules, they need those rules to bounce against, to energize them. But in the military, many rebels have said, “Look, the military is actually a good place for rebels, you could succeed here.” I think they’ve kind of figured out like, “How do we help these folks? How do we harness that energy?”

Gretchen: And so, maybe, as a manager, when you’re looking at it, you’re like, “Okay, well, some people aren’t going to do it exactly my way, but it’s not like I have to get them into line, I just have to see if they’re getting where they need to go, and maybe I give them a little bit more freedom because that’s what they need to do their best work.” Whereas other people really want a plan and a structure, and that’s how they thrive. An upholder wants structure, an upholder wants a schedule, that’s what they want, that’s not what the rebel wants. But I can have all those things available if I understand that I’m going to be… it’s not as hard as it sounds, but you just have to think about, “Well, is everybody seeing what they need to thrive?”

Brooke: Yeah, it’s interesting. As you speak, it sounds like one of the points you made is that everyone loves the autonomy-

Gretchen: But they love to do their work in their own way.

Brooke: And what we consider to be an autonomous circumstance or an autonomous context will likely vary from person type to person type. Having the kind of guardrails around me to feel that I can explore within this space safely because I know where the boundaries are, that can feel very liberating. And that, as I describe it, it sounds like someone who really wants that external accountability, they want to know where the boundaries are that they can work with them. They will feel freed by the fact that those boundaries are there, they don’t need to be constantly wondering whether they’re onside or offside. Whereas for a rebel, of course, well, I mean, in one sense, they will feel very autonomous with the boundary there because they’ll know exactly what they should be traipsing all over, right?

Gretchen: Yeah, and it’s interesting because one of the things that you see with the tendencies is that people’s values really come into play very much. And so, you could have a rebel… tendency people will say to me like, “All rebels are creative, all rebels are teenagers, all rebels are narcissists.” But I don’t know anything about your creativity based on your tendency. Maybe if I had big data, there would be correlations, but there’s nothing necessarily about the tendencies that would suggest that. And if you have a rebel who’s extremely public-minded and really wants to be environmentally conscious or whatever, very high-minded, they will do what they want to do and they’re going to be serving those values. Where if you have a rebel who just really doesn’t care what other people think or what happens to other people, it’s going to look very different.

Gretchen: And so, they both have a rebel tendency because if I ask them to do something, they would be like, “You’re not the boss of me,” because that’s what a rebel says, but their behavior might be very, very different, they may look different. So I think, sometimes people are like, all questioners are scientists or all scientists are questioners. No, they’re really not. Actually, a lot of crackpots are questioners. “I’ve looked at the research, I looked online and I came to my own conclusions and this is what I think about chemotherapy.” “Why do you think more than an MD?” Well, you did your own research, you came to your own conclusions since you’re a questioner, that’s the most important thing. Sometimes, it can look very different depending on the person’s other qualities and other values.

Brooke: Let’s get into how to make intelligent decisions about which taxonomy to use and which circumstance. So we’ll start with your area of expertise first and then wade into these waters gently, what are the types of problems for which you think picking up and using your taxonomy is the best choice? For which kinds of problems is your taxonomy best suited?

Gretchen: Problems of expectations. So anytime you have a problem, either your inner expectations or outer expectations, you won’t do what I want you to do, or I won’t do what I want me to do. That’s when it works, and that’s what it’s useful for, is managing those kinds of conflicts. I want you to practice piano, and you’re not practicing piano. You say you want to be on the soccer team, but you’re not doing your soccer practice. You say you want to get back into exercising, and I keep saying, “Fine, great. I don’t understand why you’re not keeping your promises to yourself, either do it or don’t do it, but stop talking about it because why have you been talking about it for two years?” “I want to exercise, I keep talking about it, I know how much better I’d feel, I don’t understand why I’m not doing it.” Or an upholder problem is tightening when the rules get tighter and tighter, when it’s, “Ooh, why can’t I let go of something and I feel like I have to do it even if I think I should give myself a break?”

Brooke: And looking back at the context in which you develop this taxonomy, my anticipation is that expectations are kind of the path towards behavior change and habit formation or habit change. The idea there is to help us get towards being happier.

Gretchen: Because a lot of times people misattribute, I think, the reasons why something works. So a person might say, “I’m very social, so it really worked for me to go to an exercise class because it was a very social experience.” And I’m saying, it’s not the socialness of it, it’s the accountability of it. And that might seem “who care?” but it’s actually very important to understand what’s actually at play. Because if somebody says to me, “Well, I’m an obliger but I’m very introverted, I don’t want to go to a class, because I’m already overwhelmed by how many social situations I have to be in at work and at life, I don’t want to go to a class, so I can’t do it.” No! There are many ways of having accountability that don’t require you to go to a class or to interact with somebody else face to face. Maybe you have an app, maybe you have an online trainer. There’s a lot of things you can do, there’s a million ways to create accountability. Because obligers, the biggest tendency for both men and women, that’s the biggest group of people belonging to obligers.

Gretchen: So if you understand exactly what’s at issue, it’s much easier to figure out what your range of choices would be that with most successfully. Rebels often they’re like, “I don’t understand it. Every adult can use a to-do list and I can’t use a to-do list, what’s wrong with me?” I’m like, “There’s nothing wrong with you, that’s a rebel thing. A lot of rebels can’t use to-do lists.” They’ve got all kinds of workarounds. Here’s five different things that rebels do to get the value of a to-do list without having a to-do list because the minute it’s a to-do list, they’re like, “I’m not going to do that. I’m not going to be something that somebody tells me to do even if it’s me who’s telling me what to do.” And that’s like, “Okay, well we’ll figure out something else.”

Brooke: You mentioned earlier that the framework doesn’t attempt to be exhaustive. It’s not like, this is the one tool that’s going to explain absolutely everything in all circumstances. You brought up the example before of the spin class. One way to interpret that as around external accountability. Another way to interpret that is through sociability. So if we think about the EAST framework of behavioral change, it’s very big in the behavioral science world that behaviors are really driven by how easy they are, how attractive they are, how social they are and how timely they are.

Gretchen:Here’s the thing. Often, it’s much easier to form a habit of something we don’t want to do than of something we want to do. And people often have a very hard time making habits of things they really enjoy doing.

Brooke:So this is something that I’m hoping that we can explore together. What are the types of situations where another framework might offer insights that your framework doesn’t cover? Just because that’s kind of not its wheelhouse, that’s not its focus. So, for instance, if we think about the way that people interact with pieces of technology, for instance, if we think about user experience, design and that type of thing, there are certain design principles about reducing friction and these types of things that just seem to fall outside of the scope of what it is that you’re talking about, which is not a shortcoming of your work.

Gretchen: No, 100%.

Brooke: You’re not looking to build solutions that are the right thing for every problem. What I’m trying to demarcate here is what’s the scope of problems for which the taxonomy that you’ve developed is best applied and where should we be looking at a problem and saying, “Actually, that’s kind of outside the wheelhouse of this, we should be looking for something different.”

Gretchen: Absolutely, something like “convenience” is a kind of universals of human nature, you don’t need to get into the tendencies for that. Then things like creativity. Creativity, I think operates in a separate zone. Now, you might argue, part of creativity is consistent work. Not everybody agrees with that; many people argue that. And you might say, “Well, if you want to do consistent work, then that’s starting to get into an expectation.” And then, I would start to think about the four tendencies, but maybe I think of creativity in a very different way and so I don’t even need to get into the four tendencies.

Gretchen: Things like extroversion and introversion. I mean, one thing that’s very interesting and many rebels have emailed me about this, and again, what I really need is big data that I don’t, at this point, have access to, is whether something like impulsivity is connected to the rebel tendency. Many rebels suggest that they think that it is, but I don’t know, because it may be that what other people think is impulsive, actually, isn’t really impulsive, it’s just a way of characterizing, what is a rebel behavior? Because I think rebels are the most misunderstood tendency. It’s the most different from the other three, it’s the smallest tendency out in the world. But something like curiosity, I think is completely separate on the four tendencies, I don’t think that that is related at all. So I think there’s many, many, many aspects of a person’s nature that aren’t correlated or don’t come into play, or that you would have to tackle with a different kind of tool.

Brooke: So do you have a kind of diagnosis process? Not so much the questionnaire, the self-assessment that you mentioned earlier but kind of a problem diagnosis process where you say, “I’m looking at this problem and I’m trying to figure out how to tackle it. These are the criteria that I’m looking for to figure out which approach I’m going to take.”

Gretchen: You mean in like figuring out someone’s tendency or-

Brooke: In figuring out-

Gretchen: Because I always just think about it from the upholder tendency. If I have a problem, I’m like, “how does that work for upholders? Because that’s what I am.” I’m always solving for me.

Brooke: Yeah, I mean, I must plead guilty on my own part as well whenever something doesn’t seem to be going the way that I expect it to I’m like, “Oh, it’s just because people don’t understand, I should explain more.”

Gretchen: Yes, right?

Brooke: Mansplaining has just kind of been clarified about three or four times in my mind, as I was saying that.

Gretchen: My own view is that individual differences swamp gender differences. And I think it’s very easy for people to say, “everybody does this, women do this, men do that.” And in my observation, in some ways I’m a very typical “woman,” in some ways I’m very atypical. I look at someone like my husband. In some ways, he’s very typically ‘male,’ in many ways he’s not typically male. I think a lot of times these things are not tied to gender–but it is interesting how culture can teach you how to frame your tendency in a different way.

Gretchen: So, for instance, you could imagine someone being like, “Oh, I’m an obliger, I never meet my promises to anybody else, I can’t put myself first, I don’t have any self-esteem, I never make myself a priority.” Somebody else is like, “You know what? I give 110% to my clients. You think I’ve got time to exercise? You think I got time to eat right, no way, I don’t have any time to do that kind of stuff because I am 110% for my clients, look on my wall, there’s a picture of me, my wife is delivering her baby and I’m on the phone with the client because I give everything to my clients.”

Gretchen: They’re both 100% obliger, that is obliger talk. I don’t have time for myself, my own expectations because I’m giving everything to an outer expectation. But one is like, “Oh, I’m so great, this is my best foot forward.” And the other one is like, “This is a problem, this is a limitation, this is a fault.” They’re describing the same behavior. And they’re getting to the same place which is I’m not eating healthfully and I’m not exercising because I’m busy meeting other people’s expectations. But the framing of it is very different and I think a lot of times culture comes into play and maybe how we interpret patterns that we see in our own behavior.

Brooke: There seem to be various kinds of pathological versions of these, the way that they express themselves and the way that people perhaps embrace them or don’t embrace them. Does that sound about right? The difference between this person who says, “Yeah, my life is so great. I don’t have any time to do these things because I’m 110%.”

Gretchen: Hardcore.

Brooke: “Yeah, I’m doing awesome 110% of the time. So no time to think about these other things.” That seem to be kind of a rejection of the importance or kind of failing to recognize the value of one’s internal expectations for oneself. Whereas, the other archetype that you described the same of the four types. That’s someone who says, “I don’t take time for myself.” That’s someone who is implicitly acknowledging that taking time for themselves is something they ought to do in complete contrast to this like 110% all the time. Are there some healthier or more pathological forms of how you embrace or reject certain components of these identities?

Gretchen: Absolutely, and sometimes people will say to me, “Well, which tendency is the happiest, or the healthiest, or the most productive, or the most creative or the most successful?” And what you see is not that one tendency is the best, it’s that certain people have a tendency to figure out how to harness the strengths of the tendency and really take advantage of it. And also learn how to offset the limitations and weaknesses of that tendency so that they manage to get themselves where they want to go. So for obligers, many obligers are wildly successful, Oprah Winfrey’s an obliger, Tiger Woods is an obliger, Daenerys Targaryen is an obliger, Jon Snow’s an obliger. (I can do all the Game of Thrones characters!)

Gretchen: There’re wildly successful obligers, but when you see is thaty they figure out how to get the best of that tendency and often it’s by creating accountability for all of their inner expectations. Or like questioners, sometimes questioners can fall into analysis paralysis. This is when their desire for perfect information makes it hard for them to move forward or make a decision. So questioners who recognize that this can be the dark side of their information seeking, and will figure out ways to limit it. “I’m going to use a trusted authority so I don’t have to do all my own research. I’m going to give myself a deadline, I’m going to decide by the end of next week, I’m going to experiment while it’s better to try something and see how it works and then iterate rather than think that I should just research until I get the perfect decision because maybe I’ll never get to the end of all the information that I could find.”

Gretchen: So I figured out how to deal with that, and that’s going to mean that I get all the power of the questioner tendency and figuring out ways to deal with the limitations of it. But you do see people who feel good in their tendency and kind of revel in their tendency. And then people who feel very cramped or limited by their tendency or where kind of the dark side of their tendency has taken over. And if I can just indulge in Game of Thrones, there’s a great example in Game of Thrones, do you know Game of Thrones?

Brooke: I don’t, but I am sure that many of our listeners do so, please stab at it.

Gretchen: So Stannis Baratheon is a dark upholder. He’s keeping the rules, he kind of can’t let them go. He doesn’t seem to even want to keep the rules but he feels bound. He is supposed to be King, that’s the rule. And he’s going to do everything that he can. And his foe, his nemesis, is Brienne of Tarth, who’s also an upholder, but she’s the most self-executing, where she has a vision, and she’s just going to pursue it, and there’s so much satisfaction like her just doing it. There’s a moment–spoiler alert–where these two upholders come face to face and what Stannis says to Brienne is “do your duty.” What is a more upholder thing to say? And she does. And it’s like this closing of an upholder loop. She’s like the good version of it, the happy version of it. He’s like the dark version, the cramped version, kind of imprisoned by their own expectations version.

Gretchen: And so you will see that with rebels, some rebels feel incredibly energized and in touch with their authentic feelings, and they can do anything and they’re unstoppable. But then some are like, “Gosh, I can’t even pay my bills on time, maybe I’m living off somebody else who’s doing all my work for me that’s not so great. Maybe I’m just letting every ball drop and that’s just a huge pain. Maybe I’m having trouble doing the grunt work. I’m an entrepreneur but I can’t get myself to do my invoicing. And so I have a lot of people owing me money because I just can’t sit down and get myself to do that, so that’s a drag.” So I think it’s really understanding what the kind of the strengths and the limitations are and figuring out how to deal with it. That’s what gets you to the good side and not the bad side.

Brooke: Is there one size fits all best way to kind of go through that exploration of taking stock of where you live in this taxonomy and trying to understand what the healthy ways are of embracing the certain dynamics of your type and how to relate healthily to your type.

Gretchen: I think it’s really better and easier to just do it tendency by tendency because it’s very specific to that tendency. Rigidity is a big issue for upholders. It’s not such a big issue for the other three tendencies. So there’s kind of more specific for you to the four tendencies. I don’t know that there’s anything like universal touchpoints that would surface the things that I would say, like analysis paralysis, very questioner, it’s not such an issue for the other ones. I mean, maybe it is. I would never say “never” with humans, because there’s always people who do something, but overwhelmingly that’s the questioner thing.

Brooke: So for something like analysis paralysis, you’ve surely seen lots of people in these different tendencies. Have you seen some kind of pathways that seem to be more successful? Let’s focus on this example of analysis paralysis, have you seen kind of a pattern of questioners who kind of encounter that feature of themselves respond healthily to it and then they manage to do some productive work towards either leveraging that to their benefit or minimizing its determinants or whatever it is that they’re doing versus another approach that just seemed to maybe but their heads against it over and over again and they’re just kind of not getting over the hump.

Gretchen: Well, one reason I think it’s nice to have a vocabulary and a framework is because I think it lets you see patterns in your own behavior more clearly. And so then solutions are more obvious, but I think it’s absolutely the case that even people who don’t know about the four tendencies often grope their way to solutions, because with time and experience and seeing what works for you personally, you figure out what works. Like my literary agent is a questioner, and when we were talking about the tendency when I first came up with it, she called it “the black hole of research” where it’s pulling you in, it’s this force of attraction that you can’t resist because it’s so enticing. But you know that if you get down that research black hole, you cannot come out, and it’s just a huge time suck. She recognized that in herself is that, that was an issue.

Gretchen: And so I think then they do learn how to use their tendency and limits. “Okay, maybe I’m going to set myself a limit., I’m going to interview 10 candidates for this, that’s a reasonable number. After 10, I don’t think I’m going to get that much better information so I’m going to say 10 and I’m going to stick to 10.” But always what a person should do is they should harness the value of their tendency. So for questioners, whenever they’re having something like this, I always make the appeal to efficiency, reasons, rationale, why it’s not efficient for you to postpone. At some point it’s more efficient to start. Don’t get it perfect, get it going. Learn from what doesn’t work. You’re better off not just constant delaying, in the end, is not efficient so that’s their value.

Gretchen: Whereas with a rebel, you always go to the value of “what do you want? this is what you want, this is what works for you. Why is this what you choose?” Because once they decide, “Yeah, this is what I want,” then they can do it–but they have to be very clear in their mind. So it’s always about going to that value and figuring out how to harness that value, how to get to that value through different kinds of solutions. And again, so many people are in all of these tendencies, once you know what category of solution you need, you see that in culture there’s so much conversation about all of them. They don’t necessarily use my vocabulary, but they’re all talking about the same. They’re talking about these things, but it’s easier to sort your way through all the suggestions if you know what your tendency is.

Brooke: So expectations are the watchword of the day. What can we expect from you next? Where to?

Gretchen: Oh, I am writing a book about the five senses in the body and tapping into the five senses as a way to give myself a sense of recess from life–to spur creativity and productivity and just rest and energy. It’s the most fun subject ever.

Brooke: But we’re living through the greatest recess from life that we have experienced in probably 100 years.

Gretchen: It’s interesting because it’s recess in some and in some ways, it is the opposite of recess, and so it’s interesting. I think it does shed a lot of light on… like anytime you run an experiment, you learn something. None of us would have chosen this experiment, but we’re in it, and I think we’re learning a lot about what works, what doesn’t work, it’s interesting.

Brooke: Yeah, we certainly are. Are there any dynamics that you’ve seen play out over the last few months, especially in the most intense periods of confinement as well as the opposition and from some quarters to confinement, to mask wearing, to various public health measures? Are there some things that you’ve observed in these last few months that have really made you say, “Wow,” and kind of brought a new realization to you?

Gretchen: You mentioned masks wearing, and that’s the thing where you can see the four tendencies really coming up and you can also see wherein all best intentions, people maybe are pushing people’s buttons with saying, “Well, you have to wear a mask.” “It’s the rule that you have to wear a mask.” Well, for some people that’s just going to enrage them. And some people are going to say, “You say the data says this, but I say the data says that.” And it’s like, “Okay, well, do we all get to make up the rules for ourselves?” And so I think you could think about messaging in a way that would try to be appealing to all four tendencies.

Gretchen: For instance, I live in New York City and right now, New York City people are being really, really careful because we got it so hard. So we have a lot of freedom because we do this, we have a lot of freedom, everything’s coming back. And so to say, “if you do this all year, you can have freedom, you’re going to have options. Everything’s going to open up, you’re going to be able to do everything.” This is the way of freedom. It’s not that we’re telling you what to do because this is going to let you do anything you want; rather than you have to, you must, this is the rule.

Gretchen: It’s interesting because people are often saying to me like, “I need one short message that will resonate with all four tendencies.” It’s that is hard, that is really, really hard to do, because they’re all listening for different things. And I’m often reminded of a public service announcement. It was used decades ago but people still remember it vividly, it was so effective. And I think the reason that it was so effective is because it speaks to each of the four tendencies and the message is: “Only you can prevent forest fires.” Upholder, questioner, obliger, rebel, it works for all four of them.

Gretchen: And so you think, “Well, how can we explain things in a way?” You see this sometimes in a national park, “we’re keeping this park pristine for you.” So you are the boss of us, we are not telling you what to do, we’re here to serve you or whatever. I mean, there’s a lot of ways you see different signs trying to do that. And you definitely see that around this time when there’s a lot of rules being imposed on people and people have very different ideas about that.

Brooke: Yeah, there’s another campaign that comes to mind that was also extremely successful and I believe is probably still running, if not, it’s certainly strongly imprinted on the public psyche and the one that I have in mind is Don’t Mess with Texas.

Gretchen: Oh, well that’s a brilliant one. I’m so glad you mentioned that that’s written up in the Heath books, Made to Stick, if anybody wants to read all about it. Absolutely, because what they did is instead of having the kind of environmental crunchy green thing, they’ve picked people like Willie Nelson and football players, and they were like, “Crushing a beer can, this is what I’m going to do to you if you litter. Don’t Mess with Texas.” And so the idea was that a strong, tough, true Texan protects Texas, rather than protect, whatever, the grass. So they really thought about who are the people that are littering, and what’s going to work for these people who are throwing stuff out of their truck basically, as I remember it. They studied who the litterers were, they had a very specific demographic in mind. And it’s just a brilliant example, because it was extraordinarily effective, because it changed the whole idea of what it meant to protect Texas.

Brooke: So you mentioned that they knew their audience very well and that was a key ingredient in their ability to develop and roll out such a successful campaign for anyone who is looking to kind of pick up on the work that you’re doing and try that out in the way that they’re developing messaging, what kind of indicators or what kinds of signs and signals can they be looking for to try to understand or segment their audience and to these types so that they can try to adjust the messaging right for the right people.

Gretchen: Well, that’s an interesting question because I’ve never done that on a population level, it’s much more individual the way I’ve looked at it. So there are certain kind of “tells” if you’re talking to an individual, I’m like, “Okay, I think I’m getting the message here.” Anybody who talks about spontaneity that’s a sign they’re rebel. Anybody who talks about things being arbitrary, that’s a sign of questioner. Anytime somebody thinks about self-care or breaking their promises to themselves or talks about wanting to make a promise and not keeping a promise, being disappointed in themselves, that’s a sign of obliger. Anytime somebody is giving you kind of a rigidity vibe or kind of delighting in the rules and sticking to the rules, even when nobody else knows or cares or maybe even when it doesn’t make sense anymore, that’s a sign of upholder.

Gretchen: I haven’t really thought about it on kind of a population because it’s not demographic. Because if I look at those people speeding down a Texas highway, they’re probably all four tendencies. So that was tapping into a different part of their identity. But that’s a really interesting question, and I should start to think about that because you’re right, there’ll be all kinds of applications if you could think about broad populations in that way.

Brooke: Yeah, of course, with social media and big data, you mentioned big data a number of times, with large data sets, we start to ask ourselves, well, what’s meaningful in the data? How can we structure the data to be able to extract meaningful insights? Population-level messaging is not population-level anymore. Everything is so micro-targeted by its delivery vehicle. I’m wondering how it is that we would operationalize what it is that you’ve done in a way to run some experiments and to see what kinds of dynamics we can turn up by actually gathering some data about this and testing out different messaging structures.

Gretchen: Research with the University of Michigan is trying to get a grant to study some aspects of it and how to put it to work. So, yeah, I think it would be fascinating to try to understand. And then also like, are there correlations? Here’s something interesting, okay, this is not scientific, so, okay, but I think it’s fascinating. Whenever I talk about the percentages of the tendencies, like obliger being the biggest and rebel being the smallest, all the questioners are like, “But what about selection bias? Because you say you three million people took your test but that’s selection bias.” I’m like, “Yes, I know about selection bias, thank you. I paid for a representative sample to take the study, and that’s what I’ve seen.”

Gretchen: Though I have to say like in my own life and talking to people constantly, it confirms those breakdowns. But when I did that nationally representative survey, just for fun, in addition to the questions that I put in there that I had honed for years, just because I thought it would be interesting to see what people said. I asked the question, “have you struggled with addiction?” Is addiction even real? It’s very controversial, I understand that. What is addiction? What does it mean to be addicted to something? People can have very different views.

Gretchen: So put that all aside, all I asked was the very unscientific question. “Have you struggled with addiction?” Because many rebels had said to me, “I think rebels are more likely to struggle from addiction.” Obligers had emailed me and said, “I think obligers are more ready or more likely to struggle with addiction.” And in my mind, I can spin out a hypothesis about why that might be true. So I just was curious, what did we see? Again, this is not truly scientific. I was just curious, anecdata, here we go. What I found is that questioners, obligers and rebels were all basically the same but there did seem to be something about upholders that protected them. They were less likely to say that they had struggled from addiction.

Gretchen: So it wasn’t that one of the others seemed more likely. It was that something about being an upholder made it less likely. And as an upholder myself, I have to say, there’s a lot of things about the upholder tendency, the desire to execute, the desire to perform, the desire to stay on schedule, the training aspect of it. The desire for control of discipline, upholders tend to love discipline. That is kind of a counterbalance to a lot of things that a person would find intoxicating and addicting. So I thought that was fascinating that it was not that one made you more likely, but the one made you less likely. So that’s the kind of thing that if you really did it properly, could be fascinating and really help guide decision-making.

Brooke: Don’t want to scoop your story but any sneak peeks about the work that you’re doing on the senses on the body.

Gretchen: So the senses are so fun. It’s so energizing to think about your senses, go out and eat some ketchup, ketchup is an amazing food that is making every sense, light up, that’s why we all love it, it’s really, really fun.

Brooke: Well, thank you for joining us for the podcast today. And we look forward to speaking to you again soon.

Gretchen: Thank you, it was so much fun to talk to you.

Brooke: If you’d like to learn more about applied behavioral insights, you can find plenty of materials on our website, thedecisionlab.com. There, you’ll also be able to find our newsletter which features the latest and greatest developments in the field, including these podcasts, as well as great public content about biases, interventions and our project work.

We want to hear from you! If you are enjoying these podcasts, please let us know. Email our editor with your comments, suggestions, recommendations, and thoughts about the discussion.