Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

The Basic Idea

Therapy comes in all shapes and sizes—as our world continues to face major changes, so has the way we approach mental health issues and treatment. With heightened social isolation and increasing demands in the workplace, access to different kinds of therapy has proven to be a saving grace for millions of individuals. But of all the options available— from art and animal assisted therapy to acceptance and commitment therapy and beyond—Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) remains the gold-standard.1

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy is a form of psychotherapy that helps individuals reframe negative thoughts or sensations they experience in a positive light. CBT encourages individuals to enhance their awareness of how their thoughts and feelings affect their behavior, and uses the ABC model to assist individuals in learning healthier response mechanisms.

Men are disturbed not by the things which happen, but by their opinions about the things.

– Epictetus, Greek Stoic Philosopher

Theory, meet practice

TDL is an applied research consultancy. In our work, we leverage the insights of diverse fields—from psychology and economics to machine learning and behavioral data science—to sculpt targeted solutions to nuanced problems.

Key Terms

Classical Conditioning: A form of learning in which a conditioned stimulus is associated with a separate unconditioned stimulus to generate a behavioral response known as a conditioned response.

Behaviorism: A theory suggesting that human behavior is best studied through the observable actions (behavior) rather than through the analysis of thoughts, feelings and consciousness.2

Stoicism: Stoicism is a philosophical school of thought founded in ancient Greece and Rome that promotes the maximization of positive emotions, reduction of negative emotions and aids individuals to sharpen their virtues of character.3

People

Aaron Beck

An American psychiatrist who is credited with revolutionizing the field of mental health by turning toward empirical data to validate the efficacy of the therapeutic techniques he pioneered in CBT. While Beck was trained as a psychoanalytic analyst, it was his disenchantment with the existent tools and techniques at his disposal that encouraged him to develop a whole new type of psychotherapy.3

Epictetus

An exponent of Stoicism who flourished in the early second century. Epictetus suggested individuals can train themselves to be happy by challenging their thoughts and deliberately developing calm rational thinking skills. He believed it was understanding what we can control and what we cannot control.4

History

The CBT model appeared in the early 1960s as a counterpoint to the behaviorist and humanistic psychoanalysis traditions prevalent at the time. At the time, both schools of thought shared center stage as the dominant psychotherapies of their day.

Classical behaviorism rests on the assumption that what goes on inside a person’s mind is not directly observable and therefore not amenable to scientific study. Instead, behavioralist scientists examined associations between observable events, looking for linkages between stimuli (features in the environment) and responses (observable and quantifiable reactions from the people being studied).5 Behavior therapy was developed by Joseph Wolpe and others in the 1950s and 1960s and arose as a reaction to the Freudian psychodynamic paradigm that guided psychotherapeutic practices from the 1800s onwards. In the 1950s, Freudian psychoanalysis was questioned due to a lack of empirical evidence to support its efficacy.6

Behavior therapy used the principles of classical conditioning, a learning theory used to modify behaviour and emotional reactions. Unlike the Freudian psychoanalytic technique that sought to probe the unconscious roots of a person’s trauma—as Freud famously did with ‘Little Hans’, a boy who had a fear of horses 7—behaviour therapists craft procedures to help people learn new ways of responding to traumatic triggers.

Aaron Beck, known as the father of CBT, challenged both the psychoanalytic and classical behavioralist notions, arguing that thoughts were not as unconscious, as previously theorized, and there were limitations to a purely behavioral approach.8 Instead, Beck suggested that particular types of thinking and related negative thought patterns could serve as the culprits of emotional distress.9

Beck’s theory has its roots in ancient philosophy, namely in Stoicism, a Hellinistic school of thought. Stoicism was founded by Zeno of Citium in the third century BCE and placed a significant emphasis on the therapeutic dimension of philosophy. The famous Roman stoic Epictetus is often quoted suggesting that ‘It is more necessary for the soul to be cured than the body, for it is better to die than to live badly (Fragments, 32) and “the philosopher’s school is a doctor’s clinic” (Discourses, 3.23.30).10 The Stoics held that people are not in complete control of external outcomes and should instead shift their focus to the intrinsic value of their own character traits. In practice, this means ‘doing what we can’ to exercise greater kindness, friendship, and wisdom.11

While Stoicism is more of a philosophy of life, it contributed heavily to the philosophy employed in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. Borrowing from Stoic philosopher Epictetus, CBT is built on the founding idea that it is not what happens to individuals, but rather how individuals perceive what happens to them, that determines their affect.12 CBT places a profound emphasis on the idea that we, as individual agents, are in control of our own thoughts and emotional reactions to external factors beyond our sphere of influence or control.

Consequences

The core belief underlying CBT techniques is that when people change their thoughts (or, what psychologists call cognitions) they can change how they feel and behave. The CBT framework looks to alleviate the suffering we implicate upon ourselves based on the meaning and the importance we give to what happens to us.

One helpful tactic, proposed by CBT, involves changing the way we view mental health problems. Instead of perceiving them as pathological states that are qualitatively different from normal states and processes, it’s more helpful to identify them as positioned on one end of a metaphoric continuum.

The Continuum Technique employs this thinking and is based on the idea that psychological problems do not exist in an entirely different dimension and can happen to anyone. The technique involves targeting, evaluating, and developing core beliefs by working on process features like planning and interpersonal skills.13

Traditional psychodynamic theory suggests successful treatment must uncover the hidden motivations and developmental processes ‘at the root’ of our problems. In contrast, CBT employs the Here and Now principle.14 This notion suggests the focus of therapy should be on what is happening in the present rather than the developmental events at the root of the problem.

Cognitive behavioral therapy is widely used to treat a variety of psychological issues. It has become the preferred type of psychotherapy, as it can quickly help patients identify and cope with specific challenges. The consequences, however, include feelings of emotional discomfort, physical drain, and temporary stress or anxiety as you explore painful emotions and experiences.15

Empirical research done on the efficacy of CBT has shown that it is strongly supported as a therapy for most psychological disorders in adults, and has greater support for treatment of psychological dysfunctions than any other popular form therapy.16 CBT has also demonstrated favorable long-term outcomes in youth with anxiety disorders in efficacy trials. In a 2018 study of individuals under 18 suffering from anxiety, the use of CBT induced loss of the principal anxiety diagnosis and changes in youth- and parent-rated youth anxiety symptoms.17

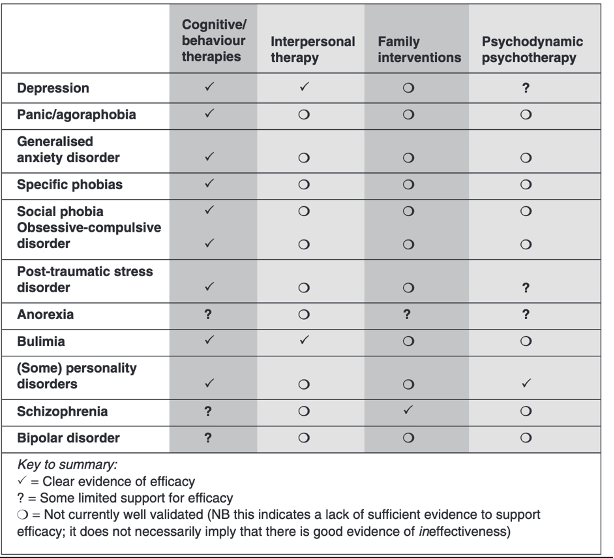

Figure 1: Ruth and Fonagy’s 2005 Study on CBT Efficacy and Effectiveness 18

Controversy

Given its dominance in therapy today, there’s no surprise that the CBT approach has garnered its fair share of critics. Conventional criticism has argued the approach is too mechanistic and doesn’t take a holistic account for the patient.18

Some significant criticisms have emerged from within the CBT community itself as well. First, the specific cognitive components of CBT often fail to outperform less-comprehensive versions of the treatment that focus mainly on behavioral strategies. For example, Jacobson et al. demonstrated that patients suffering from depression showed as much improvement following a treatment that purposefully excluded techniques designed to modify distorted cognitions, when compared to the traditional CBT approach containing both the cognitive and behavioral elements.19

Case Study

Utilizing CBT to Improve Employee Engagement

A recent study done by The Decision Lab and Hikai (a conversational employee engagement platform) on disengagement in the workplace has shown that computerized CBT can be a wildly successful remedy for employees feeling burnout, anxiety or depression at work. In a time where nearly 70% of workers in North America report feeling unengaged at work, utilizing CBT techniques in the workplace can be hugely beneficial.20 By leveraging AI and user-engagement research, TDL was able to develop an effective tool that could provide effective computerized CBT. This technique has been shown to be a very low-cost, scalable, and effective way to treat anxiety and depression.21 Chatbots have been shown to be an engaging and effective mechanism for delivering computerized CBT at scale. The study found a 71% improvement in engagement among its pilot participants, 82% of whom said the product helped them reduce stress levels.22

Related TDL Content

Behaviorism provides insight into the ‘behavior’ part of CBT, and focuses on how a person's environment and surroundings bring about changes in their behavior. Read this reference guide to learn more about behaviorism, it’s key players, controversies, and applications.

A vital part of CBT is the reorienting of unhealthy habits and coping mechanisms in response to emotional distress. This reference guide describes how we began to study habits in the first place, the learning principles that contribute to habit formation, and how habits influence our interactions with technology.

Sources

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Common Mental Health Disorders. London, England: The British Psychological Society and The Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2011.

- Behaviorism. (n.d.). In APA Dictionary of Psychology. American Psychological Association. https://dictionary.apa.org/behaviorism

- Stoicism 101: An introduction to stoicism, stoic philosophy and the stoics. (2018, March 16). Holstee. https://www.holstee.com/blogs/mindful-matter/stoicism-101-everything-you-wanted-to-know-about-stoicism-stoic-philosophy-and-the-stoics

- Grohol, J. M. (2009, September 2). A Profile of Aaron Beck. Psych Central. https://psychcentral.com/blog/a-profile-of-aaron-beck#2

- Walsh, V. (2020, March 29). CBT and the philosophy of Epictetus: ‘Events themselves are impersonal and indifferent’. Veronica Walsh's CBT Blog Dublin, Ireland. https://iveronicawalsh.wordpress.com/2014/08/21/cbt-and-epictetus-events-themselves-are-impersonal-and-indifferent/

- Westbrook, D., Kennerley, H., & Kirk, J. (2011). An introduction to cognitive behaviour therapy: Skills and applications. Sage.

- Eysenck, H. J. (1952). The effects of psychotherapy: an evaluation. Journal of consulting psychology, 16(5), 319.

- Freud, S. (1909). Analysis of a phobia in a five-year-old boy. Klassiekers Van de Kinder-en Jeugdpsychotherapie, 26.

- Diaz, K., & Murguia, E. (2015). The philosophical foundations of cognitive behavioral therapy: Stoicism, Buddhism, Taoism, and Existentialism. Journal of Evidence-Based Psychotherapies, 15(1).

- Oatley K (2004). Emotions: A brief history. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. p. 53.

- Robertson, D., & Codd, T. (2019). Stoic Philosophy as a Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy. The Behavior Therapist, 42(2).

- Robertson, D., & Codd, T. (2019). Stoic Philosophy as a Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy. The Behavior Therapist, 42(2).

- Understanding CBT. (2021, August 3). Beck Institute. https://beckinstitute.org/about/intro-to-cbt/

- James, I.A., & Barton, S.B. (2004). CHANGING CORE BELIEFS WITH THE CONTINUUM TECHNIQUE. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 32, 431 - 442.

- Westbrook, D., Kennerley, H., & Kirk, J. (2011). An introduction to cognitive behaviour therapy: Skills and applications. Sage.

- Cognitive behavioral therapy. (2019, March 16). Mayo Clinic - Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/cognitive-behavioral-therapy/about/pac-20384610

- Roth, A., & Fonagy, P. (2006). What works for Whom?: A critical review of psychotherapy research. Guilford Press.

- Roth, A., & Fonagy, P. (2006). What works for whom?: A critical review of psychotherapy research. Guilford Press.

- Kodal, A., Fjermestad, K., Bjelland, I., Gjestad, R., Öst, L. G., Bjaastad, J. F., ... & Wergeland, G. J. (2018). Long-term effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy for youth with anxiety disorders. Journal of anxiety disorders, 53, 58-67.

- Gaudiano, B. A. (2008). Cognitive-behavioural therapies: achievements and challenges. Evidence-based mental health, 11(1), 5-7.

- Jacobson NS, Dobson KS, Truax PA, Addis ME, Koerner K, Gollan JK, et al. A component analysis of cognitive-behavioral treatment for depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64:295–304.

- Folkman, J. (2019, October 10). 70% of workers aren't engaged -- What about the managers? Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/joefolkman/2014/03/06/seventy-percent-of-workers-not-engaged-what-about-the-managers/

About the Author

Rebecca Mestechkin

Becca Mestechkin is a behavioral insights specialist, passionate about applying decision-making research to improve client practice and strengthen social bonds. In addition to her work with TDL, Becca works as a research assistant investigating judgments related to behavior genetics and the ethical implications of health policy.