John Stroop

Paying attention to how we process information

Intro

John Stroop was an experimental psychologist, best known for developing the Stroop test. In this task, participants are given a list of words, printed in different colors. They are asked to read the color of each word, as opposed to the word itself, and the delay this generally causes is known as the Stroop effect. Stroop’s work opened the door to decades of research into how our brains switch between automatic and deliberate information processing. Stroop was a respected lecturer at David Lipscomb College, where he spent most of his career teaching and researching. Despite his legacy in the field of psychology, Stroop’s primary focus throughout his life was his devout Christian faith. He preached in churches across Tennessee and further afield, and published several books based on his biblical teachings. The Stroop test grew increasingly popular in the 1970s and 1980s, and is still used today in both research and clinical information-processing settings.

On their shoulders

For millennia, great thinkers and scholars have been working to understand the quirks of the human mind. Today, we’re privileged to put their insights to work, helping organizations to reduce bias and create better outcomes.

The Stroop Test

Stroop is best known for his experimental approach to psychology and his research into people’s ability to control their level of focus. In his doctoral thesis, Stroop created a task designed to show the difference in reaction time when people automatically process information versus when they engage in ‘controlled,’ or intentional, information processing.2 Sometimes we make decisions in the blink of an eye, without really thinking about them. Like when we start to make a cup of tea, we’ll go switch on the kettle and grab a mug from the cupboard. Other decisions require that we stop and think a little. Like when we are faced with 10 different tea varieties to choose from in the store. This idea that our brain sometimes processes information automatically, and other times requires us to use intentional effort, is a fundamental assumption for many psychologists.

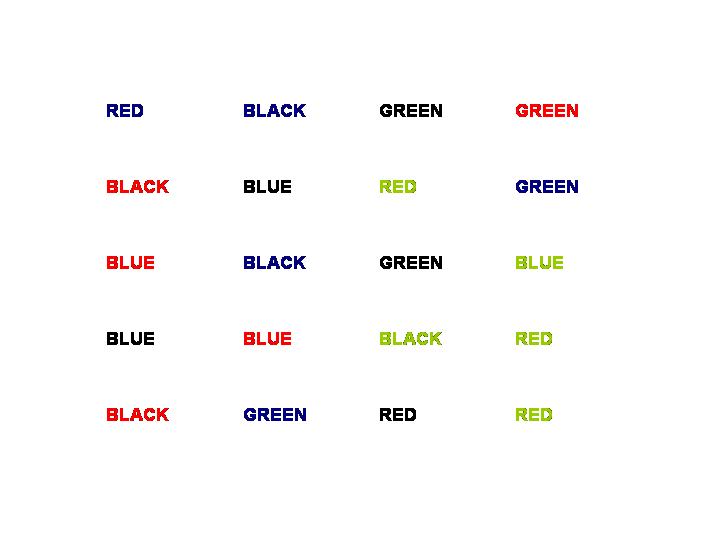

Stroop’s test was designed to illustrate this exact argument. The test consists of a list of colors printed in a color different from the one they denoted. For example, the word ‘green’ was shown in red ink, and so forth. Participants were asked to name the color of the word’s print (to engage in controlled processing), as opposed to reading the word itself (automatic processing), as quickly as possible. Give it a try below:

As you can see, it is natural for our brains to read the word, rather than to name the color of the ink - thus, reading can be categorized as an automatic process. Stroop’s test wasn’t the first to address this interesting aspect of our cognition.1 James McKeen Cattell, with the help of his supervisor Wilhelm Wundt (the man credited with developing psychology as a science), developed a test to measure the time it took people to name and categorize objects, while reading various words. However, Stroop was the first to come up with the idea of mixing up the word and its associated characteristic, in the same stimulus (e.g. the word ‘red’ printed in blue ink). He called such examples ‘incongruent stimuli’, as opposed to ‘congruent stimuli’, which would be the color ‘red’ printed in red ink.

Stroop’s discovery sparked some interest when it was first published in The American Journal of Experimental Psychology in 1935, however it wasn’t until the 1970s, and after his death, that it really grew in prominence. In fact, Stroop pretty much took a step back from psychology in the years following his PhD, choosing to focus on his biblical teachings instead.1 His research acted as a blueprint for an abundance of future studies, most notably in attentional studies and neuroscience, where researchers have succeeded in identifying the fronto-parietal network as the region of the brain responsible for the Stroop effect. For example, we now know that It also supports the findings of dual process theory, the most famous example being Daniel Kahneman’s System 1 and System 2 model which describes how people make automatic and deliberate decisions. While several studies have tried to pinpoint the exact cause of our delayed reaction to incongruent stimuli, it’s likely a combination of factors, including the attentional bias: our tendency to focus on certain elements of stimuli while ignoring others.

A modified version of the Stroop test emerged in the late 1980s, when psychologists began to consider the influence of affect and emotion on individual test performance. In the ‘emotional Stroop test’, people are still asked to name the color of a word, but the words themselves are categorised as either positive (e.g. ‘flowers’, ‘vacation’), or negative (e.g. ‘fear’, ‘dark’). Some really fascinating observations have been made in this context. For instance, people suffering from depression are slower to name the colors of negative words4, and anxious patients are slower when presented with threatening words, particularly words that remind them of their specific fear or worry.5

Today, the Stroop Test is most commonly used in clinical settings. Psychologists use it to diagnose children with learning disabilities, and help support their development. It’s also been applied to identify phobias, and to diagnose individuals with schizophrenia and ADHD. For example, poor performance in the Stroop Test is associated with a deficit in selective attention, a key indicator in a ADHD diagnosis.2

Biography

John Ridley Stroop was born in Murfreesboro, Tennessee in March 1897. The family owned a small farm, and John was the second youngest of six children. His academic career began at David Lipscomb College in Nashville, where he graduated first in his class in 1921. It was also in this year that Stroop married Zelma Dunn. They went on to have three children.5

In 1933, Stroop was awarded his PhD in experimental psychology from George Peabody College, where he had focused his work on cognition and attention. His dissertation was published in The American Journal of Experimental Psychology in 1935, and later evolved into the test for which he is best known. After the Stroop Test took off, Stroop pretty much left the field of experimental psychology. In fact, he only published two more papers on the color-word task. After his PhD, Stroop spent most of his career at David Lipscomb College. There, he lectured, conducted research, and even served as Registrar of the college for eleven years, and then as chair of the Psychology Department from 1948 to 1964.

Although his career was devoted to psychology, almost every other aspect of Stroop’s life revolved around his devout Christian faith. As Colin MacLeod of the University of Toronto puts it, “The Bible, not psychology, was his life's work.”1 Starting in his mid-20s, Stroop preached at various churches every Sunday, often travelling long distances to do so. He kept detailed records of where he had preached, and the topics of his sermons. As a lecturer at David Lipscomb, he taught Bible classes alongside his psychology courses, and offered numerous seminars that aimed to teach young students ‘how to live life according to the Bible.’ He also published several religious books based on his biblical teachings, including the trilogy ‘God's Plan and Me.’

Stroop passed away in 1973, aged 76. He remains one of the most cited authors in experimental psychology, as his test set a strong foundation for future research in the psychology of attention and information-processing. Today, it is still widely used in clinical practice and research.

References

- MacLeod, C. M. (1991). John Ridley Stroop: Creator of a landmark cognitive task. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie canadienne, 32(3), 521. Retreived March 5 from https://pure.mpg.de/rest/items/item_2355499/component/file_2355498/content

- Simply Psychology. (2020). Stroop Effect. Retrieved 5 March 2021, from https://www.simplypsychology.org/stroop-effect.html

- Gotlib, I. H., & McCann, C. D. (1984). Construct accessibility and depression: An examination of cognitive and affective factors. Journal of personality and social psychology, 47(2), 427.

- Mathews, A., & MacLeod, C. (1986). Discrimination of threat cues without awareness in anxiety states. Journal of abnormal psychology, 95(2), 131.

- Abilene Christian University. (2021). About John Ridley Stroop. Retrieved 5 March 2021, from https://blogs.acu.edu/johnridleystroop/about-john-ridley-stroop/#.YEKtO2j7Q2w

About the Authors

Dan Pilat

Dan is a Co-Founder and Managing Director at The Decision Lab. He is a bestselling author of Intention - a book he wrote with Wiley on the mindful application of behavioral science in organizations. Dan has a background in organizational decision making, with a BComm in Decision & Information Systems from McGill University. He has worked on enterprise-level behavioral architecture at TD Securities and BMO Capital Markets, where he advised management on the implementation of systems processing billions of dollars per week. Driven by an appetite for the latest in technology, Dan created a course on business intelligence and lectured at McGill University, and has applied behavioral science to topics such as augmented and virtual reality.

Dr. Sekoul Krastev

Sekoul is a Co-Founder and Managing Director at The Decision Lab. He is a bestselling author of Intention - a book he wrote with Wiley on the mindful application of behavioral science in organizations. A decision scientist with a PhD in Decision Neuroscience from McGill University, Sekoul's work has been featured in peer-reviewed journals and has been presented at conferences around the world. Sekoul previously advised management on innovation and engagement strategy at The Boston Consulting Group as well as on online media strategy at Google. He has a deep interest in the applications of behavioral science to new technology and has published on these topics in places such as the Huffington Post and Strategy & Business.