Why do we mispredict how much our emotions influence our behavior?

Empathy Gap

, explained.What is Empathy Gap?

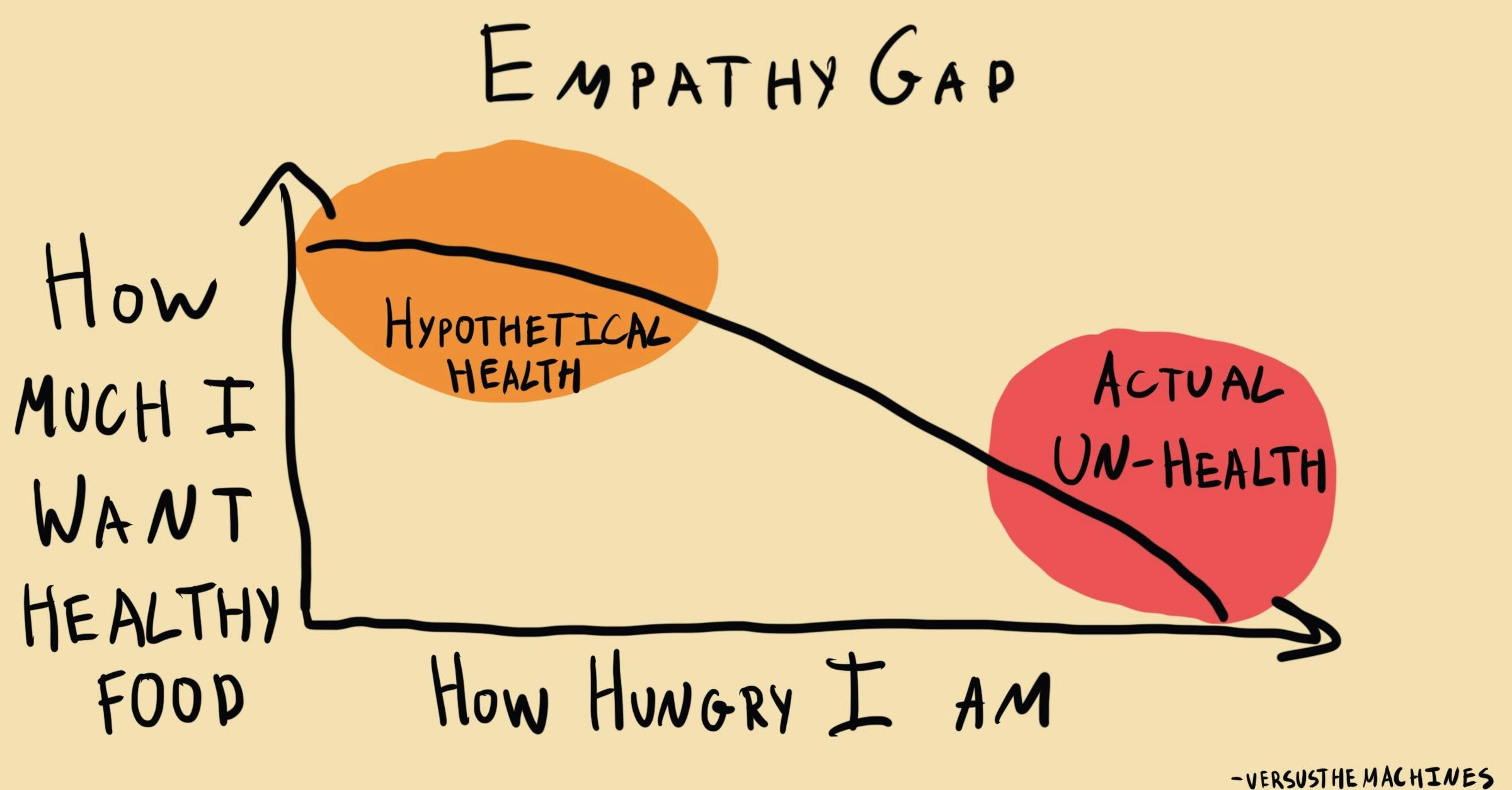

The empathy gap describes our tendency to underestimate the influence of varying mental states on our own behavior and make decisions that only satisfy our current emotion, feeling, or state of being.

Where this bias occurs

The empathy gap is also sometimes referred to as the hot-cold empathy gap. This is a reference to two kinds of visceral states. ‘Hot’ visceral states are when our mental state is influenced by hunger, sexual desire, fear, exhaustion, or other strong emotions. A ‘cold’ mental state is one that is not being influenced by emotion and is usually more rational and logical.1 When we are in either a hot or cold mental state, we fail to acknowledge the temporary nature of that mental state, and can’t put ourselves in the mindset of the other. Either we overpredict how rational we will be or believe that we will always feel as heated as we do in an emotional state.

For example, imagine that you are asked how you would respond in a situation where there was an unconscious person in need of help. Since you are currently not in that intense situation, you might have a very rational response, such as claiming that you would perform CPR. You predict a logical response because you are currently in a “cold” state of mind. However, if you found yourself in that situation, fear and anxiety might cause you to behave very differently. You would be in a hot mental state and powerful emotions may influence how you behave. This situation demonstrates the empathy gap, where we are unable to correctly predict how we will behave because we make our predictions based on current emotional states.

Debias Your Organization

Most of us work & live in environments that aren’t optimized for solid decision-making. We work with organizations of all kinds to identify sources of cognitive bias & develop tailored solutions.

Individual effects

The empathy gap means we make incorrect predictions about our future behavior. It is related to the projection bias, which refers to our tendency to overestimate how much our future self will share the same tastes and preferences as our current self. Both biases mean that we make decisions only considering our narrow, short-term state, instead of considering the fact that emotions influence our current mental state to a great degree. Short-sighted decisions can lead to behavior that is not in our best interest. If we are in a hot mental state, we may make rash and impetuous decisions that cause us to act recklessly. For example, if we receive an email from our boss that makes us very angry, we may send a nasty email back, not considering that our anger would likely eventually subside, and this can have negative consequences on our job.

Alternatively, when we aren’t being influenced by visceral emotions, we may believe that we will have a higher degree of control over our own behavior in situations that these emotions are aroused. For example, imagine you have made a decision to quit drinking and one morning, a friend invites you to a party where other people will be drinking. When you make the decision to go, you are not in a highly emotional state. However, when you get to a party, your visceral state changes and you become very anxious and may be tempted to drink. If you’d been able to predict your behavior in a different mental state, you likely wouldn’t have made the decision to put yourself in a difficult situation.

As these examples demonstrate, the empathy gap acts as an obstacle for making the best decision for our long term goals, and it can occur in either direction, from hot-to-cold or cold-to-hot.

Systemic effects

Economic models, which are used in order to predict human behavior, are predicated on the assumption that humans make rational decisions. Emotions are usually left out of the equation but the empathy gap demonstrates that emotions manipulate our decision-making process. Although we may strive to be rational decision-makers, we need to acknowledge the way that our visceral states make us act, in order to be able to better predict our future behavior when our emotional mindset has changed. Economic models need to be reconfigured to more aptly reflect the imperfect, not always rational beings that we actually are.

Moreover, while the empathy gap is often discussed in relation to our inability to understand how our own behavior will differ depending on our emotional state, it follows that we are also inaccurate in predicting other people’s behavior. An interpersonal empathy gap can occur when we fail to consider how other people may be affected by their emotions.2 If we are in a cold state, and our friend does something while angry, we may believe that their behavior is ridiculous and unwarranted because we are not empathizing with the power of their emotions. The empathy gap is also a problem when it comes to our ability to understand the perspective of others, which can lead to conflict.

Why it happens

George Loewenstein, Ted O'Donoghue and Matthew Rabin, important behavioral economists, have suggested that our current emotional states are used as an “anchoring point” for our tastes, behaviors, and beliefs.3 That means that we rely too heavily on our current mental state to predict our future behaviors. Although we would like to be perfectly rational decision-makers, on a daily basis, we are constantly asked to make predictions about our future behavior and it is difficult not to be influenced by emotions.

When we are really thirsty, or hungry, it is almost impossible for us to make decisions that aren’t based on those emotions, but we also fail to understand that our decisions are being influenced by our hot state. Similarly, when we are in a cold state, we would like to believe that we will also behave in a logical manner in the future, and make the same decisions as we now would. In either case, we downplay the role of emotions in decision-making because we would like to think we act according to ration.

Why it is important

As various examples in this article have demonstrated, the empathy gap comes into play in many different situations, because on a daily basis, we are asked to make predictions about our future behavior. As the empathy gap stipulates that we are not very accurate in our predictions, it follows that we are not able to make decisions that reflect our long-term goals. It is important to know about the empathy gap, as by being aware, we can try and counter its effects.

How to avoid it

Emotions are incredibly powerful influences, which often supersede rationality and logic. This makes it difficult for us to avoid their impact on our decision-making. However, the empathy gap is a problem of not being able to correctly identify the power of emotions. Therefore to avoid the empathy gap, although we may not be able to shut off our emotions, we can become better predictors. We need to acknowledge the way that emotions distort our actions instead of pretending we are always rational decision-makers.

One technique for becoming better at making predictions is to ensure that we consider not only our future actions but our future mental states as well. Before being able to predict what we may do, we need to be able to predict how we may feel.2

How it all started

The hot-cold empathy gap was coined by George Loewenstein, a well-known and influential figure in behavioral economics.4 Loewenstein stated that “affect has the capacity to transform us, profoundly, as human beings; in different affective states, it is almost as if we are different people”(1).4 Through a series of studies that he has either led or been a part of, Lowenstein has demonstrated the empathy gap in response to pain, addiction, thirst, and fear.

Loewenstein first observed the empathy gap in relation to the powerful emotion of pain in 1999, with Daniel Read, a professor at the University of Leeds.4 In the experiment, participants were asked to rate their willingness to endure pain for a monetary reward, a scenario that would occur one week after the question had been posed. The pain that they had to endure was putting their hands in ice-cold water. Participants had to indicate how much money they’d have to receive to be willing to endure the pain. Participants were asked to indicate their willingness in one of three conditions. The first group was given a sample of what the pain would feel like right before making their decision, the second group had experienced a sample of the pain a week before, and the last group had no experience of the pain.

Read and Loewenstein found that participants in the first group, who had just experienced pain before making their decision, indicated that they would need the largest monetary reward to endure the pain, followed by the participants who had endured it a week later.4 Participants who had never experienced a sample of the pain indicated the lowest compensation. The researchers concluded that the pain that participants in the first group were experiencing caused them to make decisions based on their emotional state. They may have underestimated how willing they’d be to endure pain for a monetary reward because they believed they would still have the same feelings one week later. Alternatively, the participants who hadn’t experienced the pain were not as likely to have their decision influenced by emotions, which caused them to accept lower monetary compensation. They may have overestimated their willingness to endure pain because they were currently in a rational, calm mindset.

This self-forecasting error was later coined the empathy gap.

Example 1 - The empathy gap and addiction

Louis Giordano, a professional counselor, worked with Loewenstein in order to examine whether the empathy gap was involved in the predictive behavior of drug addicts.4

Giordano asked drug addicts to predict how much money they would choose over a maintenance drug that helps with withdrawal symptoms, five days from when they were being asked. For example, they were asked to pick whether they’d prefer $10 or another dose of the maintenance drug, $20 or another dose, etc.

The addicts were asked either before receiving a dose of the maintenance drug (opioid deprived), or after. Giordano and Loewenstein believed that individuals were in very different states before compared to after receiving a dose, and therefore that when the question was asked would affect the amount of money people chose over a maintenance drug.4

The experiment revealed that participants who were asked before receiving a dose of the maintenance drug on average said they’d accept $60 instead of another next dose five days from then, whereas those that were asked the question after receiving a dose on average said they’d choose just $35 over another dose.5 From these results, Giordano and Loewenstein concluded that participants who had been asked after receiving the maintenance drug were in a cold visceral state and did not accurately predict how they would feel in a hot state five days later when they had not just received a dose.4

Example 2 - Projecting our emotions onto others

As has been mentioned, the empathy gap is a bias that also affects our attitudes towards others. Loewenstein worked with Leaf Van Bowen, professor of psychology and neuroscience, to examine the interpersonal empathy gap.4

For their study, Loewenstein and Bowen hypothesized that people would project their own visceral state onto others, thereby allowing their emotions to influence their prediction of other’s behavior.4 In the experiment, participants were asked to predict the feelings of hikers that had gotten lost in the woods without food or water, and how they themselves would feel if they were the hikers. After being asked to describe how they believed the hikers would feel, the participants were also asked questions to make predictions about the hikers’ hunger and thirst. One example of a question was “Which would be more unpleasant for the hikers, hunger or thirst?”. Participants were then asked about their own visceral state.

Participants answered these questions in one of two groups. The first group answered these questions immediately before partaking in 20 minutes of cardiovascular exercise, while the other group answered the questions immediately after engaging in 20 minutes of cardiovascular exercise. Loewenstein and Bowen found that participants who answered the questions after exercising were more likely to indicate thirst as the more unpleasant feeling and that not bringing water warranted more regret than not bringing food, both for their predictions of how the hikers would feel and how they would feel if they were in the hikers’ position.4

From these results, the researchers concluded that participants that had just exercised before answering the questions were in a hot visceral state, and were letting their own thirst influence their predictions both about how they would behave in a certain scenario, and how other people would feel. Loewenstein and Bowen concluded that the empathy gap is a bias that affects both self-forecasting predictions and our ability to predict others’ behavior.4

Summary

What it is

The empathy gap describes our inability to correctly identify how our emotions impact our behavior.

Why it happens

The empathy gap occurs because we underestimate how much emotions impact the decisions that we make, causing us to leave emotions out of the equation when making predictions. We look to our current feelings and attitudes to give us an idea of how we might behave in the future, but depending on whether we are in a cold or hot visceral state, our actions may be very different.

Example 1 - The empathy gap and addiction

Addiction leads to very high emotional states in withdrawal that greatly impact behavior. However, when an addict is currently not experiencing withdrawal because they have just received a maintenance drug, they are likely to overestimate how much withdrawal would impact their need for the drug at a later date and may believe they’d make decisions that are more similar to actions they take in a cold state.

Example 2 - Projecting our emotions onto others

The empathy gap is not only a bias that makes us unable to predict our own behavior but also makes us less likely to understand the behavior of others who are in a different visceral state. We are likely to project our current emotions onto other people and predict that their behavior reflects what our decisions would be considering our visceral state instead of realizing that they may be in a different mental state.

How to avoid it

It is almost impossible for us to avoid the influence of emotions on our behavior, so instead, it is important that we acknowledge their impact. The empathy gap is mostly an issue that causes us to incorrectly predict our future behavior, which means that understanding that the way we feel, not just rational logic, impacts how we act, we can take emotions into account in our predictions.