Why do our decisions depend on how options are presented to us?

Framing Effect

, explained.What is the Framing Effect?

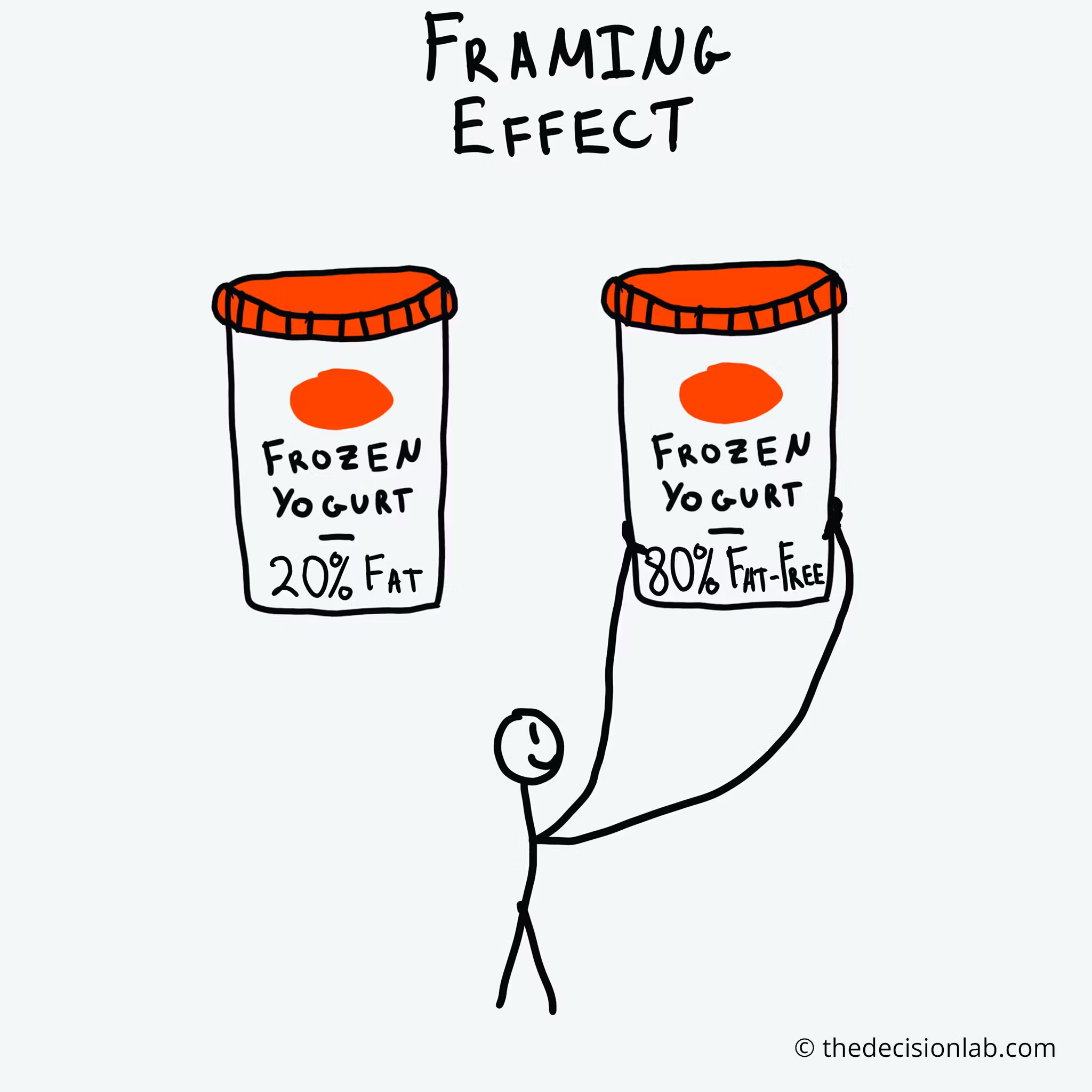

The framing effect is when our decisions are influenced by the way information is presented. Equivalent information can be more or less attractive depending on what features are highlighted.

Where this bias occurs

Consider the following hypothetical: John is shopping for disinfectant wipes at his local pharmacy. He sees several options, but two containers of wipes are on sale. One is called “Bleachox” and the other is called “Bleach-it.”

Both of the disinfectant wipes Jon is considering are the same price and contain the same number of wipes. The only difference Jon notices, is that the Bleachox wipes claim to “kill 95% of all germs,” whereas the “Bleach-it” wipes say: “only 5% of germs survive.” After comparing the two, John chooses the Bleachox wipes. He doesn’t like the sound of germs ‘surviving’ on his kitchen counter.

John’s decision to buy the Bleachox over Bleach-it wipes was informed by the framing effect. Although both products were equally effective at fighting germs, and essentially claimed the same thing, their claims were framed differently. Bleachox highlighted the percentage of germs it did kill (a positive attribute), whereas Bleach-it highlighted how many germs it did not kill (a negative attribute).

Debias Your Organization

Most of us work & live in environments that aren’t optimized for solid decision-making. We work with organizations of all kinds to identify sources of cognitive bias & develop tailored solutions.

Related Biases

Individual effects

Decisions based on the framing effect are made by focusing on the way the information is presented instead of the information itself. Such decisions may be sub-optimal, as poor information or lesser options can be framed in a positive light. This may make them more attractive than options or information are objectively better, but cast in a less favourable light.

Think of someone who unwisely chooses a high-risk investment portfolio because their broker emphasized the upside instead of the potential downside, or a citizen who votes for a protectionist candidate because media coverage has only highlighted the negative repercussions of past trade agreements.

Systemic effects

The framing effect can have considerable influence on public opinion. Public affairs and other events that draw attention from the public can be interpreted very differently based on how they are framed. Sometimes, issues or positions that benefit the majority of people can be seen unfavorably because of negative framing. Likewise, policy stances and behaviour that do not further the public good may become popular because their positive attributes are effectively emphasized.1

For example, there is an overwhelming amount of evidence showing that climate change will result in enormous costs further down the line, and that those costs will be disproportionately borne by low income communities.2 Despite this, there are a significant number of voters in North America who deny climate change and believe policies such as carbon taxes will disadvantage the average citizen. This may be because climate change has been framed as a scientifically contentious issue by some media outlets and politicians, who also often highlight the short-term financial costs of environmental policy.

Why it happens

Our choices are influenced by the way options are framed through different wordings, reference points, and emphasis. The most common framing draws attention to either the positive gain or negative loss associated with an option. We are susceptible to this sort of framing because we tend to avoid loss.

We avoid loss

The foundational work of psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky explains framing using what they called “prospect theory.” According to this theory, a loss is perceived as more significant, and therefore more worthy of avoiding, than an equivalent gain.3 A sure gain is preferred to a probable one, and a probable loss is preferred to a sure loss. Because we want to avoid sure losses, we look for options and information with certain gain. The way something is framed can influence our certainty that it will bring either gain or loss. This is why we find it attractive when the positive features of an option are highlighted instead of the negative ones.

Our brain uses shortcuts

Processing and evaluating information takes time and energy. To make this process more efficient, our mind often uses shortcuts or “heuristics.” The availability and affect heuristic may contribute to the framing effect. The availability heuristic is our tendency to use information that comes to mind quickly and easily when making decisions about the future. Studies have shown that the framing effect is more prevalent in older adults who have more limited cognitive resources, and who therefore favour information that is presented in a way that is easily accessible to them.4 Because we favour information is easily understood and recalled, options that are framed in this way are favoured over those that aren’t.

The affect heuristic is a shortcut whereby we rely heavily upon our emotional state during decision-making, rather than taking the time to consider the long-term consequences of a decision. This may be why we favor information and options that are framed to elicit an immediate emotional response. Research has shown that framing relies on emotional appeals and can be designed to have specific emotional reactions.5 Picture this: most of us would be more willing to listen and vote for a political candidate that presents their platform in an emotional speech framed at inspiring change, over a candidate with the same platform that is presented it in a dreary report.

Why it is important

The framing effect can have both positive and negative impacts on our lives. As mentioned above, it can impair our decision-making by shedding a positive light on poor information or lesser options. In other words, overvaluing how something is said (its framing) can cause us to undervalue what is being said, which is usually more important. As a result, we may choose worse options that are more effectively framed over better options or information that is framed badly. This holds true in the smaller decisions we make as consumers and citizens, as well as more significant decisions in our personal and professional lives.

However, we should also be aware of this effect because it can be harnessed to our advantage. Understanding that people are influenced by framing can make us focus on how we present information we want others to accept and act on. Knowing that people are drawn to framing that highlights certain gains can help us present our work in this fashion, making it more attractive and effective. When managing or collaborating with other people, it is important to remember the importance of how we present our message or position. More effective framing may allow us to better leverage our point of view.

– Management communication lecturer Melissa Raffoni

What exactly does it mean to “frame” or “reframe” an issue? Think about the metaphor behind the concept. A frame focuses attention on the painting it surrounds. Different frames draw out different aspects of the work. Putting a painting in a red frame brings out the red in the work; putting the same painting in a blue frame brings out the blue. How someone frames an issue influences how others see it and focuses their attention on particular aspects of it. Framing is the essence of targeting a communication to a specific audience.

– Management communication lecturer Melissa Raffoni

How to avoid it

There are a few strategies for reducing the framing effect. Research has shown that people who are more “involved” on an issue are less likely to suffer from framing effects surrounding it. Involvement can be thought of as how invested you are in an issue. A 2010 study found that “people who are involved with an issue are more motivated to systematically process persuasive messages and are more interested in acquiring information about the product than people who are less involved with the issue.” More involved individuals were found to be less susceptible to the framing effect, whereas those who were less involved were more susceptible.

What we can take from these findings, is that we should think through our choices concerning an issue and try to become more informed on it. Indeed, the authors posit that previous literature has found that “framing bias would be mitigated or eliminated if individuals thought more carefully about their choices” and that “when older adults examined more information relevant to the decision, they made more effective decisions”.7

A more specific strategy that falls in line with this more general approach is to provide rationales for our choices. A 1997 study found this reduced framing effects in participants as it forced them to engage in more detailed mental processing.8 This makes sense: If we really think through why we selected an option or relied on certain information, we might realize that the way in which it was presented influenced our decision too much.

How it all started

Isreali psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahnemann were the first to systematically study and prove the framing effect’s influence on our decision-making. Their 1979 study established the aforementioned “prospect theory,” and two years later, they turned to a more exclusive focus on framing effects in The Framing of Decisions and the Psychology of Choice.

In this study, Tversky and Kahneman asked participants to decide between two treatments for 600 people who contracted a fatal disease. Treatment A would result in 400 deaths, and treatment B had a 33% chance that no one would die but a 66% chance that everyone would die. This was done with either positive framing (how many people would live) or negative framing (how many people would die). Treatment A received the most support (72%) when framed as saving 200 lives, but dropped significantly (to 22%) when framed as losing 400 lives. This demonstrated that the choices we make are also influenced by the way they are framed.9

Example 1 - Plea bargaining in court

Framing effects have been shown to influence legal proceedings. A paper written in 2004 by Stephanos Bibas, a U.S. law professor and judge, looked into how various cognitive biases influence plea bargains in legal trials. He concluded that “framing plays a powerful role in plea bargaining.”

Bibas argued that defendants are less likely to accept plea bargains because they view them through a “loss frame.” That is to say, because defendants are used to being free, and are being faced with a loss of freedom in a plea bargain—even if it is a lesser loss than a conviction without a plea bargain—they are more likely to resist bargaining. Defendants with a loss frame see acquittal as the baseline, and anything worse than this as a loss. Bibas believes this advantages prosecutors, as defendants often stand to gain from concessions and bargaining.

However, he goes on to claim that some defendants see plea bargains through the lens of gains. A defendant that has been in pretrial detention for some time “is more likely to view prison as the baseline and eventual freedom as a gain, particularly if freedom is possible in weeks or months.” So, as a result of pre-trial detention and the gain frame that often ensues, defendants are more likely to accept a plea bargain.10

Example 2 - Cancer treatment preferences

A 1989 study by US health science professor Annette O'Connor examined the influence of framing on patients’ preferences surrounding cancer chemotherapy. The study was composed of two groups of participants: the first group was made up of 129 healthy volunteers, and the other of 154 cancer patients. Both groups were asked to choose between two cancer treatment options. The first treatment option was toxic, while the second was non-toxic but less effective than the toxic option.

The option was framed to participants in one of three ways: probability of living (a positive frame), probability of dying (a negative frame), probability of living and dying (a mixed frame). Results showed that when the probability of living was below 50%, and framed negatively as a probability of dying, participants were less likely to choose the more effective toxic treatment. O'Connor concludes that “a negative frame or probability level below 0.5 would seem to stimulate a “dying mode” type of value system in which quality of life becomes more salient in decision making than quantity of life.”11

From a broader public health perspective, it is useful to understand the influence that framing has on patients' decisions surrounding treatment.

Summary

What it is

The Framing effect is when our decisions are influenced by the way information is presented. Equivalent information can be more or less attractive depending on what features are highlighted.

Why it happens

The most common framing draws attention to either the positive gain or negative loss associated with an option. We are susceptible to this sort of framing because in accordance with “prospect theory,” we tend to avoid certain losses. A loss is perceived as more significant, and therefore more worthy of avoiding, than an equivalent gain. The way something is framed can influence our certainty that it will bring either gain or loss. This is why we find it attractive when the positive features of an option are highlighted instead of the negative ones.

“Heuristics” or mental shortcuts might also play a role. Due to the availability heuristic, we favor information that is easily understood and recalled. Options and information that is framed this way are favored over those that aren’t. The affect heuristic may cause us to favor information and options that are framed to elicit an immediate emotional response. Research has shown that framing relies on emotional appeals and can be designed to have specific emotional reactions.

Example 1 - Plea bargaining in court

Framing effects have been shown to influence legal proceedings. A 2004 paper concluded that framing has a significant role in plea bargaining in legal proceedings. The author argues that defendants are less likely to accept plea bargains because they view them through a “loss frame.” Defendants are used to being free, and are being faced with a loss of freedom in a plea bargain—even if it is a lesser loss than a conviction without a plea bargain—they are more likely to resist bargaining. This advantages prosecutors, as defendants often stand to gain from concessions and bargaining. However, a defendant that has been in pretrial detention for some time “is more likely to view prison as the baseline and eventual freedom as a gain, particularly if freedom is possible in weeks or months.” So, as a result of pre-trial detention and the gain frame that often ensues, defendants are more likely to accept a plea bargain.

Example 2 - Cancer treatment preferences

A 1989 study examined the influence of framing on patients’ preferences surrounding cancer chemotherapy. The results showed that when the probability of living was below 50% and framed negatively as a probability of dying, patients were less likely to choose more toxic yet more effective treatment options. From a broader public health perspective, it is useful to understand the influence that framing has on patients' decisions surrounding treatment.

How to avoid it

A 2010 study found that “people who are involved with an issue are more motivated to systematically process persuasive messages and are more interested in acquiring information about the product than people who are less involved with the issue.” What we can take from these findings, is that we should think through our choices concerning an issue and try to become more informed on it. A more specific strategy that falls in line with this more general approach, is to provide rationales for our choices. A 1997 study found this reduced framing effects in participants, as it forced them to engage in more detailed mental processing.