Why can we not perceive our own abilities?

Dunning–Kruger Effect

, explained.What is the Dunning-Kruger Effect?

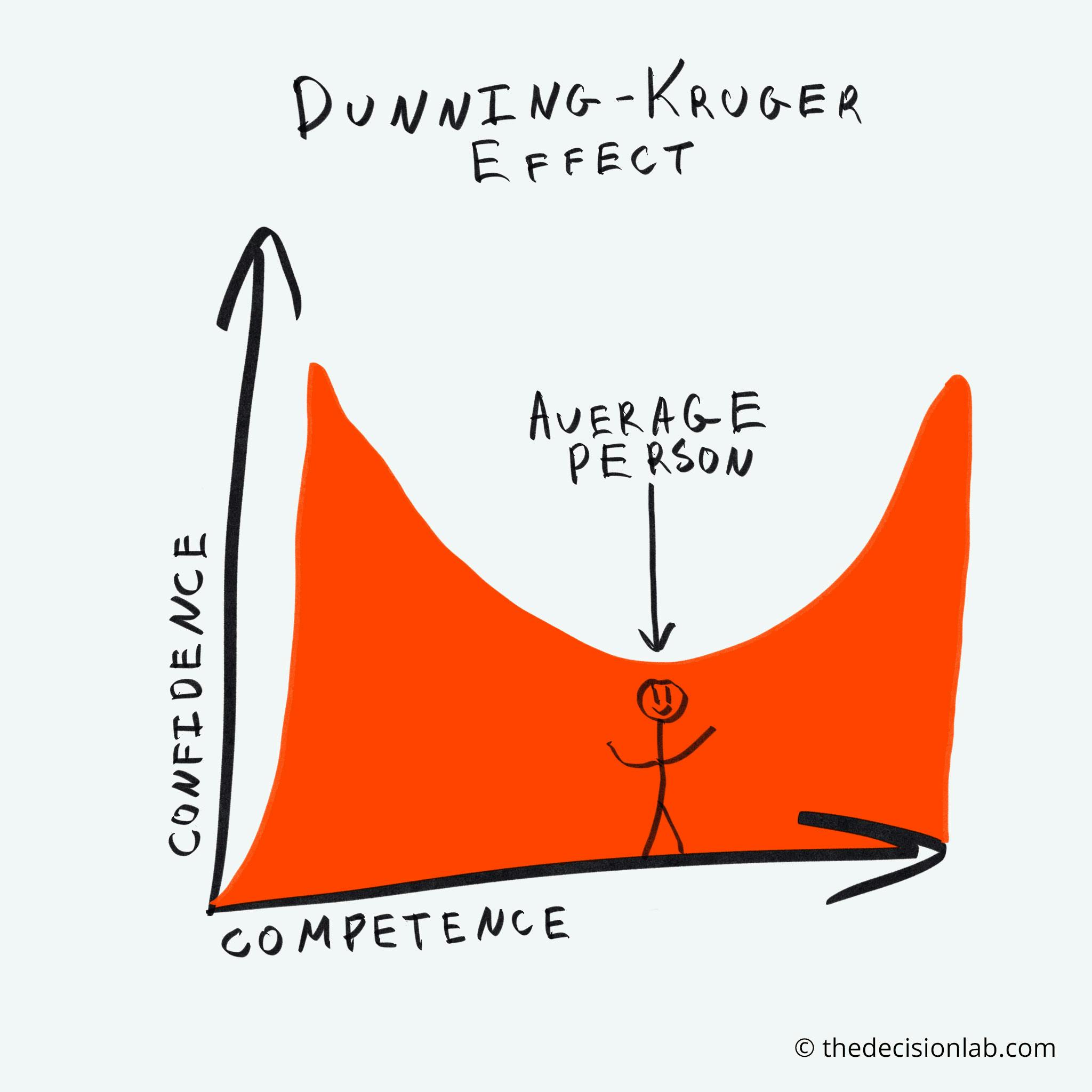

The Dunning-Kruger effect occurs when a person’s lack of knowledge and skill in a certain area causes them to overestimate their own competence. By contrast, this effect also drives those who excel in a given area to think the task is simple for everyone, leading them to underestimate their abilities. In the years following the first description of this phenomenon, controversy has surrounded the Dunning-Kruger effect and its validity. While it was once considered a well-founded explanation of how we evaluate our abilities, the effect has since been questioned by certain data scientists and mathematicians alike.

Where this bias occurs

Imagine you and your friend decide to try something new: separately, you both start learning Spanish. Within a few days, you can say 10–15 sentences. You’re a bit disappointed, and believe you should be able to say more by now. The language comes naturally to you, and having a good grip on it yourself causes you to think it is simple for everyone.

Your friend, by contrast, has learned just a few words. He is amazed by his progress. He doesn’t yet have the knowledge and skills to know that he’s pronouncing those words incorrectly and forming grammatically incorrect sentences. He’s learned much less than you, but his minimal knowledge prevents him from understanding his mistakes. Moreover, his lack of comparison causes him to overestimate his relative ability. His ignorance of how far others have come (like you, for example) keeps him thinking he’s excelling when he’s actually learning at below-average speed.

Debias Your Organization

Most of us work & live in environments that aren’t optimized for solid decision-making. We work with organizations of all kinds to identify sources of cognitive bias & develop tailored solutions.

FAQ

Are the areas where Dunning Kruger is more prevalent?

Weirdly enough, yes! Different sets of circumstances can come together and create a ‘perfect storm’ of elements that make us fall prey to the Dunning Kruger effect. Finance and investing is a very popular example of this - amateur investors (and professional ones as well) overestimate their ability… by a lot! In fact, a commonly cited statistic is that only 5% of day traders are profitable long term. And yet, people continue to trade and lose money because they feel like they have a chance at being in this 5%.

Is Dunning Kruger about people or about the environment?

All biases are about people, but in this case the environment has a much bigger influence than in most other biases. One really important element is the ability to attribute losses to the environment and wins to yourself. For example with investing, it’s quite easy to feel like you made 10$ because you’re smart but lost 10$ because the market is volatile. Thinking this way repeatedly might create an idea in your mind that despite your overall losing streak, you’re actually a genius investor. So, if you want to avoid falling prey to Dunning Kruger, you might want to think about what environments in your life (e.g. driving) create this kind of feedback loop for you.

Can Dunning Kruger happen in groups?

Absolutely. A big part of the work we do at The Decision Lab has to do with identifying and overcoming biases in organizational contexts, and the Dunning Kruger effect is one of the ones we identify the most often. It can come up in a variety of easy (e.g. a culture of managers not connecting well with employees because they have a hard time putting themselves in novice shoes; a product manager assuming that users should just “get” the feature despite usability tests indicating otherwise; an investment group making decisions with much higher confidence than is warranted by their past performance).

Individual effects

As a result of the Dunning-Kruger effect, you may not know what you’re good at. You assume that what comes easily to you also comes easily to everyone else. Therefore, you are robbed of the ability to spot your own specialties and talents.

Moreover, when you feel like you’re excelling at something new or challenging, you might accidentally fall prey to the belief that you have stumbled upon one of your talents. In reality, you may just be a below-average performer, finally approaching average levels.1

As you can see, this discrepancy may cause you to make less informed decisions surrounding opportunities or careers you pursue. You may have found yourself turning to peers asking, “What am I good at?” to gain some clearer insight. Understanding the Dunning-Kruger effect can help you discern when to trust your own abilities and when to seek out advice from others who can see you in a more objective light.

Dunning–Kruger and mental health

Being blind to our unique strengths can greatly impact our well-being and mental health. This can give rise to imposter syndrome, or persistent feelings of being a fraud People suffering from imposter syndrome may feel undeserving of their own success or may worry constantly about what will happen when others realize the “truth.”

The effect can also cause you to become disappointed when your self-recognized “talents” are not recognized by others. Perhaps you expect an upcoming promotion, only to be passed over for somebody else. It’s possible that the Dunning–Kruger effect created unrealistic expectations given your job performance, setting you up for disappointment and frustration.

Thinking you are better than you are at something can cause you to miss out on opportunities to learn from others who are truly more skilled or knowledgeable. Following the above example, if you believe that you are already doing a fantastic job at work, you’re less likely to seek out feedback to help you improve. On the flip side, thinking you are average at something when you really demonstrate great skill can cause you to miss out on opportunities for self-advancement or to guide and mentor others.

The Dunning-Kruger effect and AI

Artificial intelligence is a powerful tool that can aid in bypassing the various cognitive biases that often bog down human decision-making. However, humans still play a vital role in interpreting the output of these systems in order to make decisions. Overconfidence in our ability to prompt and understand AI systems can lead to inaccurate information, negatively impacting decision-making.

For example, imagine a business analyst unfamiliar with a particular AI tool but is wishing to use it to forecast future sales. Because they have used different tools in the past, they feel confident in their ability to work with this new system. What they don’t realize is that they overloaded the system with too much information, causing the program to make inaccurate predictions. Zooming out, if the company decides to make strategic decisions based on how the analyst prompted the AI, there is room for much error.

Conversely, because of their advanced understanding and skill, programmers and computer scientists who create these systems may overestimate the knowledge of the everyday user. This can lead to similar conclusions stemming from user error.

Systemic effects

The Dunning-Kruger effect hurts our society because it holds talented people back from unleashing their full capabilities. Meanwhile, those who are the least skilled overestimate themselves the most,3 and may be more likely to pursue leadership roles or other positions of power. Not only are overconfident individuals extremely resistant to being taught — since they believe they know the most — but they are also guilty of sharing the most information (read: misinformation).

At its core, the Dunning-Kruger effect preys on just that, not a lack of information but rather an abundance of misinformation. When individuals present information confidently, we are more likely to believe them, regardless of whether or not the information they are sharing is well-founded.

On a global level, this effect has dangerous consequences. Politicians and other public figures may benefit from a trusting and overconfident audience. People who aren’t as well-informed about political and world issues are likelier to believe what you say, consider themselves educated, and share their views with others.

How it affects product

The Dunning–Kruger effect can make it hard for product teams to understand and empathize with the user. If designers overestimate their own knowledge or expertise, they may skimp on user testing ahead of a product launch — but without objective data to guide design decisions, it’s much more likely that the user will end up with a subpar experience. By the same token, those with good ideas, or proper experience creating applications or products may feel that they are no better than their colleagues, losing out on potential successes.

With this being said, there are steps that leaders can take to evaluate their product teams and properly assess their abilities in order to boost productivity. It is important to consider how employees tasked with creating products take feedback. If they are reluctant to listen or dismiss the criticism regarding obvious design flaws, it may be a sign that they are overconfident in their ability. This can also be applied to the testing phase of a product when participants are recruited to pilot new items, applications, or devices. If the designer is unwilling to listen to the opinions of the user, it can lead to major consequences for the success of a product and the brand as a whole.

Why it happens

The Dunning-Kruger effect is a bit of a catch-22. People who don’t know much about a given subject don’t have the knowledge or skills to spot their own mistakes or knowledge gaps. Because of these blind spots, they can’t see where they’re going wrong, and they, therefore, assume they’re doing fine.

On the contrary, people who are at the top of their game in a certain subject area don’t have the ability to notice their own skill. Because their work comes so naturally to them, they don’t realize that other people experience things differently. The ease with which they pick up these skills or knowledge areas blinds them to the fact that the work is more challenging for others. Rather than underestimating themselves, they overestimate that everyone else’s abilities match their own.

Although the Dunning–Kruger effect has been found to occur in fields and subject matters as diverse as emotional intelligence, logical reasoning, financial knowledge, and even medical knowledge, there are recent doubts about its accuracy as a bias of the human brain. Some research has suggested that since computer-generated data is also subject to the effects of Dunning-Kruger, it is a computational phenomenon and thus cannot count as a bias of the human mind.2

Why it is important

The Dunning-Kruger effect makes us aware of our own blind spots and lends us the opportunity to adjust our self-perceptions. For those who fall victim to the effect, it can be difficult to adjust our personal evaluations. Doing so requires taking a step back to realize that your own self-assessments can be biased and sometimes incorrect. If you are making choices based on your own personal knowledge and skills, you have likely not consulted enough reputable information.

Also, when others make claims about their skills, it is vital to make your own observations and consult other sources before being convinced that they deserve anything from you (your business, for example). Even if the individual thinks that they are excelling, they may be wildly ignorant and grossly overestimating their own performance.

The Dunning-Kruger effect can cause us to listen to confident people before reputable people. This can have major effects in a multitude of domains. By the rules of the Dunning-Kruger effect, we accept information and advice from those who will speak first and loudest before those whose words will hold the most merit.

Dunning-Kruger effect controversies

The underlying cause of the Dunning-Kruger effect is widely disputed. In its original explanation in 1999, Dunning and Kruger cited a lack of metacognitive ability – individuals cannot judge their performance accurately because they’re ignorant of both their own skill level and that of experts.

This has been challenged by many theorists, a popular claim being that the effect is nothing more than a statistical artifact (specifically an autocorrelation). In other words, instead of a systematic bias in human cognition, the Dunning-Kruger effect is just something that emerged from the study’s original design.7

An alternative explanation proposed by researchers Krueger and Mueller states that poor performers are not unaware of their own skill; rather, it’s a combination of two different effects that create the appearance of wild exaggerations. To observe the Dunning-Kruger effect, one must sample both objectively low-skilled and high-skilled performers in a given task. As more samples are collected both “expert” and “novice” data points begin to rank closer to the average. This effect is called “regression to the mean.” Coupled with the better-than-average effect, some critics cite this as the reason why individuals make inaccurate predictions about their abilities.9

The better-than-average and worse-than-average effects have greater replicability than the Dunning-Kruger effect. These cognitive biases illustrate that we are all susceptible to believing that we demonstrate above-average performance on certain common tasks (like cleaning) but also assume that we are below-average performers when it comes to more challenging assignments (like writing an advanced physics exam). The catch is that we cannot all be above or below the average mathematically. We tend to hyperfocus on our own performance and negate that some people excel or fail at certain tasks.8

How to avoid it

When it comes to the Dunning-Kruger effect, comparing yourself to others may not be the worst thing you could do — just don’t tell your therapist we said so.

You can avoid being ignorant of your own performance by listening and gaining insight into the performances of others. If your friend, who knew only a few Spanish words, had asked how the lessons were going for you, your response might clue him into the fact that he’s not all that great at the language after all. Moreover, his poor pronunciation might show you that you have an unknown knowledge of languages.

Simply knowing about the Dunning-Kruger effect can also help to mitigate its effects. Remember that thinking you’re bad at something likely puts you in the middle of the pack because it means you have enough insight to recognize your own incompetencies. Being overconfident could also signify that you have some growing to do. It is important to take a step back and seek input from other sources.

Lastly, you can avoid the Dunning-Kruger effect by being open to feedback, which is, of course, easier said than done. Low performers do not receive criticism well and are chronically disinterested in self-improvement. Rather than brushing off the feedback and constructive criticism, attribute the critique to your lack of knowledge and use it mindfully to move forward.

How it all started

The Dunning-Kruger effect was first discovered and written about in 1999, by researchers David Dunning and Justin Kruger at Cornell University.

The researchers spotted how much people overestimated their own abilities in daily life and coined the term “dual burden.” This was used to describe that overly confident people can suffer from two things: ignorance and also, ignorance of their own ignorance. Dunning and Kruger tested participants on various subjects, including humor, grammar, and logical reasoning. They found that people who ranked in the bottom 25% of any of these test scores tended to predict themselves to be at the top of the pack. When they scored in the 12th percentile, they estimated themselves to be in the 62nd. Conversely, people in the top 25% predicted their scores to be slightly lower than they actually were.1

Analyses of these results attributed the discrepancies in self-estimation to metacognitive skill (the ability to think about your own thinking). In effect, improving the skills of the participants—on humor, grammar, and logical reasoning—helped them recognize the limitations of their own abilities and predict their own scores better on subsequent trials.

The researchers conducted a similar study on Cornell students emerging from final exams. They asked the students to predict their own test scores and then followed up when they got their real results. Dunning and Kruger found that the effect was also consistent in this organic circumstance.4

Example 1 – Dunning–Kruger at work

In one study, 42% of employees at a high-tech software engineering company assessed their own performance as being in the top 5%. Of course, this is mathematically impossible. It is important, however, because it shows the learning and growth opportunities that we may lose out on in the corporate world.

If 42% of your employees think that 95% of the company operates at levels below themselves, that means 42% of employees will not take opportunities to learn from those who are actually in the top 5%. They may think they know best and, therefore miss chances to grow and develop their skills.6

Meanwhile, if the real top 5% don’t see themselves as particularly talented, they may miss leadership opportunities like professional development, teaching fellowships, or even mentoring incoming employees. Self-awareness of employees’ performances can greatly impact company growth and development.

Example 2 – Dunning–Kruger on the road

Studies have shown that about 80% of people rate themselves as “above-average drivers,” a statistic that is (once again) mathematically impossible.

An inflated sense of ability when driving can cause drivers to make rash decisions and get into accidents. Real novices — those with less than six months of driving experience — are eight times more likely to be involved in an accident. This is not necessarily only because they are ill-equipped as drivers but also because they are overconfident. Thinking they have more control over the wheel than they actually do causes them to make reckless moves on the road, leading to an alarming number of crashes and increased insurance rates. However, if accounting for lack of skill alone, the number of these crashes could decrease significantly.

Summary

What it is

The Dunning-Kruger effect is a phenomenon illustrating that those who are overconfident in their ability may not actually be the top performers, whereas those who believe they are average, or even slightly below, often demonstrate great skill. It is also important to keep in mind that the Dunning-Kruger effect has been brought into question, and many academics now believe it is a statistical artifact rather than a real psychological effect.

Why it happens

Those who lack knowledge about a given task may also lack the insight that they need to know that they could do better. Not knowing much about something causes them to miss their own mistakes, and lose the opportunity to improve.

For those at the top, the effect occurs because a task or a subject area has become more natural to them. Thus, they don’t realize it is challenging to others, causing them to downplay the extent to which they stand out.

Example 1 - Dunning-Kruger at work

At a software engineering company, 42% of employees predicted they would be ranked in the top 5%. The lack of self-awareness at many corporations can have huge effects on companies. It may cause employees to miss learning and teaching opportunities.

Example 2 - Dunning-Kruger on the road

Having less than six months of experience as a driver makes you eight times more likely to get in an accident. The obvious reason behind this is that you haven’t had much practice. An additional reason is that your own ignorance makes you overconfident, causing you to make reckless decisions and quick turns.

How to avoid it

Avoiding the Dunning-Kruger effect involves seeking feedback from others who can help you improve, rather than staying stuck in your inaccurate self-perceptions. Also, it is important to gain insight into others’ abilities to get more realistic data about where you stand and adjust your perceptions accordingly. Bottom line: if people are telling you you’re an expert, listen.

Related TDL articles

Hard-Easy Effect

The hard-easy effect is a prediction bias that affects our ability to judge how we will perform on tasks of varying difficulty. Specifically, this effect causes us to overestimate how well we do on challenging tasks while underestimating our competency on easier ones.

Optimism bias

The optimism bias leads us to believe that we are more likely to experience positive events rather than negative ones. This can have varying consequences on an individual’s life and may influence their decision-making.