Why do we compare everything to the first piece of information we received?

Anchoring Bias

, explained.What is the Anchoring bias?

The anchoring bias is a cognitive bias that causes us to rely heavily on the first piece of information we are given about a topic. When we are setting plans or making estimates about something, we interpret newer information from the reference point of our anchor instead of seeing it objectively. This can skew our judgment and prevent us from updating our plans or predictions as much as we should.

Where this bias occurs

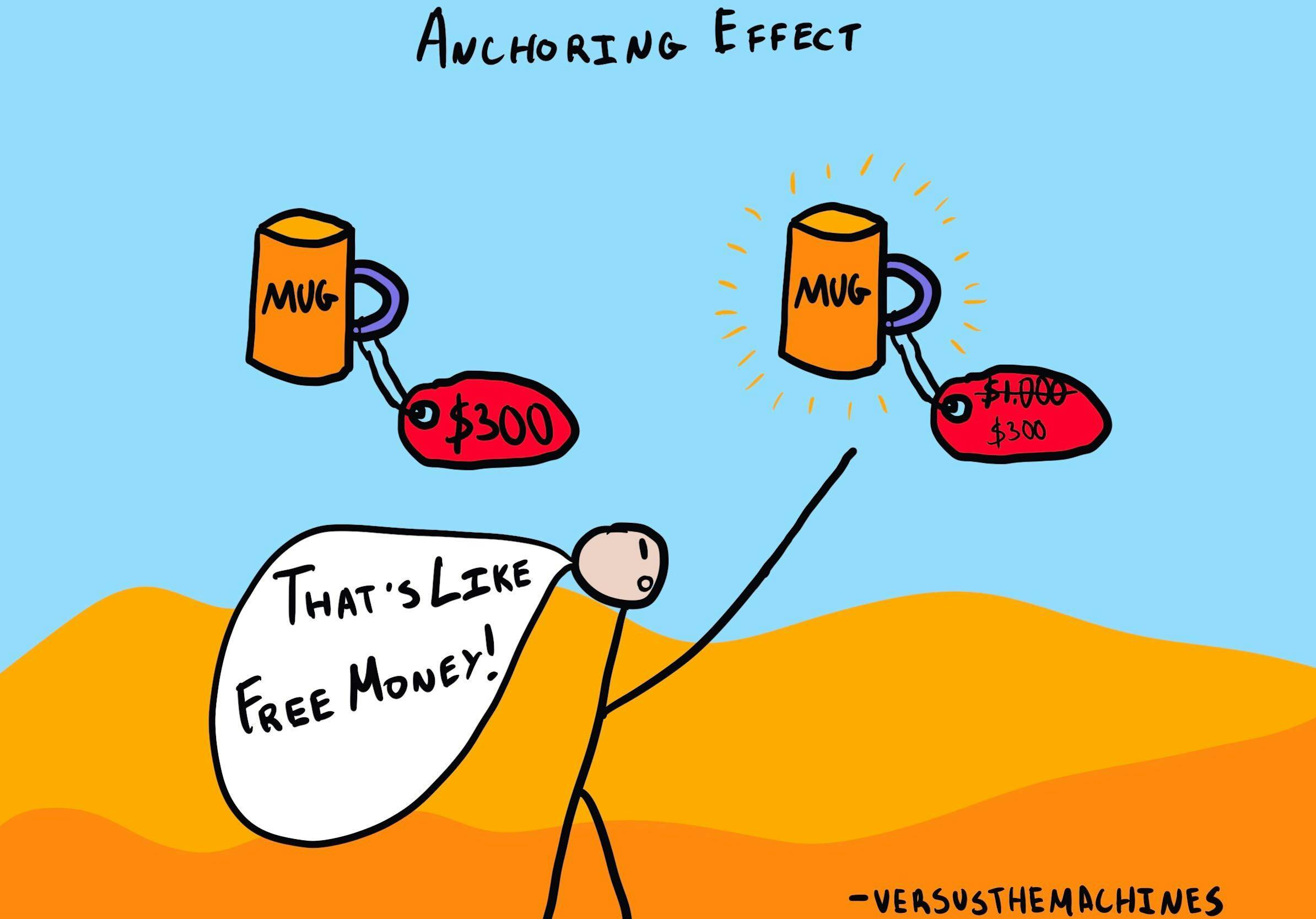

Imagine you’re out shopping for a present for a friend. You find a pair of earrings that you know they’d love, but they cost $100, way more than you budgeted for. After putting the expensive earrings back, you find a necklace for $75—still over your budget, but hey, it’s cheaper than the earrings!

Debias Your Organization

Most of us work & live in environments that aren’t optimized for solid decision-making. We work with organizations of all kinds to identify sources of cognitive bias & develop tailored solutions.

Individual effects

When we become anchored to a specific figure or plan of action, we end up filtering all new information through the framework we initially drew up in our head, distorting our perception. This makes us reluctant to change our plans significantly, even if the situation calls for it.

Systemic effects

The anchoring bias is extremely pervasive, and it’s thought to drive many other cognitive biases, such as the planning fallacy and the spotlight effect. Anchoring can influence courtroom judgments, where research shows that prison sentences assigned by jurors and judges can be swayed by providing an anchor.2,3

How it affects product

Anchoring contributes to how customers perceive the value of an item and how they compare a product to the alternatives. Applied to pricing, we can use the example of offering discounts and sales. Anchoring can have both positive and negative effects depending on the price that the individual is exposed to first. If a customer first sees a product at its original, non-discounted price, this number will become an anchor. If they subsequently see a discount offer, they will evaluate this as a great deal! Similarly, if the customer is first exposed to the product at a reduced rate, returning later to the standard price may be viewed as unreasonably high.

The anchoring bias and AI

The responses we get from AI machine learning models can potentially trigger the anchoring bias and thus affect decision-making. A response provided by an AI tool may cause individuals to formulate skewed perceptions, anchoring to the first answer they are given. This allows us to disregard other potential solutions and limits us in our decision-making.14

After being exposed to an initial piece of information, feeling short on time and being preoccupied with many tasks is thought to contribute to insufficient adjustments.15 But this can be avoided by taking the time and effort to avoid jumping to conclusions. A study by Rastogi and colleagues found that when people took more time to think through the answers provided by the AI, they moved further away from the anchor, decreasing the effect on their decision-making.14

Why it happens

The anchoring bias is one of the most robust effects in psychology. Many studies have confirmed its effects and have shown that we can often become anchored by values that aren’t even relevant to the task at hand. In one study, people were asked for the last two digits of their social security number. Next, they were shown a number of different products, including items like computer equipment, bottles of wine, and boxes of chocolate. For each item, participants indicated whether they would be willing to pay the amount of money formed by their two digits. To illustrate, if somebody’s number ended in 34, they would say whether or not they would pay $34 for each item. After that, the researchers asked what the maximum amount was that the participants would be willing to pay.

Even though somebody’s social security number is nothing more than a random series of digits, those numbers affected their decision-making. People whose digits amounted to a higher number were willing to pay significantly more for the same products when compared to those with lower numbers.9 The anchoring bias also holds when anchors are obtained by rolling dice or spinning a wheel, even when researchers remind people that the anchor is irrelevant.4

Given its ubiquity, anchoring appears to be deeply rooted in human cognition. Its causes are still being debated, but the most recent evidence suggests that it happens for different reasons depending on where the anchoring information comes from. We can become anchored to all kinds of values or pieces of information, regardless of whether we came up with them ourselves or were provided with them.4

When we come up with anchors ourselves: The anchor-and-adjust hypothesis

The original explanation for the anchoring bias comes from Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman, two of the most influential figures in behavioral economics. In a 1974 paper called “Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases,” Tversky and Kahneman theorized that when people try to make estimates or predictions, they begin with some initial value, or starting point, and then adjust from there. The anchoring bias happens because the adjustments aren’t usually significant, leading to faulty decision-making. This has become known as the anchor-and-adjust hypothesis.

To back up their theory of anchoring, Tversky and Kahneman ran a study where high school students were instructed to guess the answers to mathematical equations in a very short period of time. For example, within five seconds, the students were asked to estimate the product:

8 x 7 x 6 x 5 x 4 x 3 x 2 x 1

Another group was given the same sequence, but in reverse:

1 x 2 x 3 x 4 x 5 x 6 x 7 x 8

The median estimate for the first problem was 2,250, while the median estimate for the second was 512. (The correct answer is 40,320). Tversky and Kahneman argued that this difference arose because the students were attempting partial calculations in their heads, and then adjusting these values to reach an answer. The group who was given the descending sequence was working with larger numbers to start with, so their partial calculations brought them to a larger starting point, which they became anchored to (and vice-versa for the group with the ascending sequence).5

Tversky and Kahneman’s explanation works well to demonstrate the anchoring bias in situations where people generate an anchor on their own.6 However, in cases where the anchor is provided by some external source, the anchor-and-adjust hypothesis is not as supported. In these situations, the literature favors a phenomenon known as selective accessibility.

The selective accessibility hypothesis

This theory relies on priming, another prevalent effect in psychology. When people are exposed to a concept, they become primed, meaning that the areas of the brain related to that concept remain activated. This makes the concept easily accessible and thus capable of influencing people’s behavior without their realizing.

Priming is a robust and ubiquitous phenomenon that plays a role in many other biases and heuristics—and as it turns out, anchoring might be one of them. According to this theory, when we are initially presented with an anchoring piece of information, we build a mental representation of the target and test whether the anchor is a plausible value. For example, if I were to ask you whether the Mississippi River is longer or shorter than 3,000 miles, you might try to imagine the north-south extension of the United States, and use that to try to figure out the answer.7

As we’re building our mental model and testing out the anchor on it, we end up activating other pieces of information that are consistent with the anchor. As a result, we become primed with all of this information, and the likelihood that it affects our decision-making increases. However, the activated information lives within our mental model for a specific concept, so the anchoring bias is stronger when the primed information is applicable to the task at hand. So, after you answered my first Mississippi question, if I were to follow it up by asking how wide the river is, the anchor I gave you (3,000 miles) shouldn’t affect your answer as much, because, in your mental model, this figure was only related to length.

To test this idea, Strack and Mussweiler (1997) had participants fill out a questionnaire. First, they made a comparative judgment, meaning they were asked to guess whether the value of a target object was higher or lower than a provided anchor. For example, they might have been asked whether the Brandenburg Gate (the target) is taller or shorter than 150 meters (the anchor). After this, they made an absolute judgment about the target, such as being asked to guess how tall the Brandenburg Gate is. However, for some participants, the absolute judgment involved a different dimension than the comparative judgment—like asking about a structure’s width instead of its height.

The results showed that the anchor effect was much stronger if what we are being asked to measure or estimate is the same for both questions,7 lending support to the theory of selective accessibility. This does not mean that the anchor-and-adjust hypothesis is incorrect, however. Instead, it means that the anchoring bias relies on multiple, different mechanisms, and it happens for different reasons depending on the circumstances.

Bad moods weigh us down

Research suggests that there are a number of factors that influence the anchoring bias. One of which is mood: evidence shows that people in a sad mood are more susceptible to anchoring, compared to others in a good mood. This result is surprising because historically, experiments have found the opposite to be true: happy moods result in more biased processing, whereas sadness causes people to think things through more carefully.4

This finding makes sense in the context of the selective accessibility theory. If sadness makes people more thorough processors, that would mean that they activate more anchor-consistent information, which would then enhance the anchoring bias.8

Why it is important

The anchoring bias is one of the most pervasive cognitive biases. Whether we’re setting a schedule for a project or trying to decide on a reasonable budget, this bias can skew our perspective and cause us to cling to a particular number or value, even when it’s irrational.

Anchoring is so ubiquitous that it is thought to be a driving force behind a number of other biases and heuristics. One example of this is the planning fallacy, a bias that describes how we tend to underestimate the time we’ll need to finish a task, as well as the costs of doing so. Once we set an initial plan for completing a project, we can become anchored to it, which in turn makes us reluctant to update our plan—even if it becomes clear that we will need more time or a higher budget. This can have significant consequences, especially in the business world, where there could be a lot of money tied up in a venture.1

How to avoid it

Avoiding the anchoring bias entirely likely isn’t possible, given its pervasiveness and how powerful it is. Like all cognitive biases, the anchoring bias is subconscious, meaning it’s difficult to interrupt. Even more frustrating, strategies that intuitively sound like good ways to avoid bias might not work with anchoring. For example, it’s usually a good idea to take one’s time with making a decision, and think it through carefully—but, as discussed above, thinking more about an anchor might actually make this effect stronger, resulting in more anchor-consistent information being activated.

One evidence-based and straightforward strategy to combat the anchoring bias is to come up with reasons why that anchor is inappropriate for the situation. In one study, experts were asked to judge whether the resale price of a certain car (the anchor) was too high or too low, after which they were asked to provide a better estimate. However, before giving their own price, half of the experts were also asked to come up with arguments against the anchor price. These participants showed a weaker anchoring effect, compared to those who hadn’t come up with counterarguments.10

Considering multiple options is always a good idea to aid in decision-making. This strategy is similar to that of red teaming, which involves assigning people to oppose and challenge the ideas of a group.11 By building a step into the decision-making process that is specifically dedicated to exposing the weaknesses of a plan, and considering its alternatives, it may be possible to reduce the influence of an anchor.

How it all started

The first mention of the anchoring bias was in a 1958 study by Muzafer Sherif, Daniel Taub, and Carl Hovland. These researchers were running a study in psychophysics, a branch of psychology that investigates how we perceive the physical properties of objects. This particular experiment involved having participants estimate the weights of objects. They used the term “anchor” to describe how the presence of one extreme weight influenced judgments of the other objects.4 The anchoring effect wasn’t conceptualized as a bias that affected decision-making until the late 1960s, and it wasn’t until the 1970s that Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky introduced the anchor-and-adjust hypothesis in order to explain this phenomenon.

Example 1 – Anchors in the courtroom

In the criminal justice system, prosecutors and attorneys typically demand a certain sentence for those convicted of a crime. In other cases, a sentence might be recommended by a probation officer. Technically speaking, the judge in a case still has the freedom to sentence a person as they see fit—but research shows that these demands can serve as anchors, influencing the final judgment.

In one study, judges were given a hypothetical criminal case, including what the prosecutor in the case demanded as a prison sentence. For some of the judges, the recommended sentence was 2 months; for others, it was 34 months. First, the judges rated whether they thought the demand was too low, too high, or adequate. After that, they indicated what they would assign as a sentence if they were presiding over the case.

As the researchers expected, the anchor had a significant effect on the length of the sentence prescribed. On average, the judges who had been given the higher anchor gave a sentence of 28.7 months, while the group given the lower anchor had an average sentence of 18.78 months.12 These results show how sentencing demands might color a judge’s perception of a criminal case, and could seriously skew their judgment. Clearly, even people who are seen as experts in their fields aren’t immune to the anchoring bias.

Example 2 – Anchoring and portion sizes

As most of us know from experience, it’s easier to end up overeating when we are served a large portion compared to a smaller one. Interestingly, this effect might be due to anchoring. In a study examining the anchoring bias and food intake, participants were asked to imagine being served either a small or a large portion of food, and then to indicate whether they would eat more or less than the given amount. Next, the participants were asked to specify exactly how much they believed they would eat. The results showed that participants’ estimates of how much they would eat were influenced by the anchor they had been exposed to. To illustrate, if the participant was exposed to the larger portion, their predictions of how much they believed they would eat were larger than those who were exposed to the smaller portion This effect was found even when participants had been told to discount the anchor.13

Summary

What it is

The anchoring bias is a pervasive cognitive bias that causes us to rely too heavily on information that we received early in the decision-making process. Because we use this “anchoring” information as a point of reference, our perception of the situation can become skewed.

Why it happens

There are two dominant theories behind the anchoring bias. The first one, the anchor-and-adjust hypothesis, says that when we make decisions under uncertainty, we start by assigning some initial value and subsequently adjusting it, but our adjustments are usually insufficient. The second one, the selective accessibility theory, says that the anchoring bias happens because we are primed to recall and notice anchor-consistent information.

Example 1 - Anchors in the courtroom

In criminal court cases, prosecutors often demand a certain l sentence for the accused. Research shows these demands can become anchors that bias the judge’s decision-making.

Example 2 - Anchoring and portion sizes

The common tendency to eat more when faced with a larger portion might be explained by anchoring. In one study, participants' estimates of how much they would eat were influenced by an anchoring portion size (large or small) they had been told to imagine previously.

How to avoid it

The anchoring bias is difficult (if not impossible) to completely avoid, but research shows that it can be reduced by considering reasons why the anchor doesn’t fit the situation well.

Related articles

How Does Anchoring Impact Our Decisions?

This article explores how anchoring can affect our decisions as consumers. Beyond just influencing how we think about an item’s price, evidence shows that it can also affect our perception of its quality. Here we also explore some other mechanisms that might contribute to the anchoring bias.

Does Anchoring Work In The Courtroom?

This article goes into depth about another study on the effects of anchoring in criminal law cases. Rather than using a more naturalistic scenario, like the experiment described above, this study investigated whether the anchoring bias still occurred when the anchoring information was arbitrary, or even random (as in a dice throw). The results, dishearteningly, showed that these anchors still had a big effect.