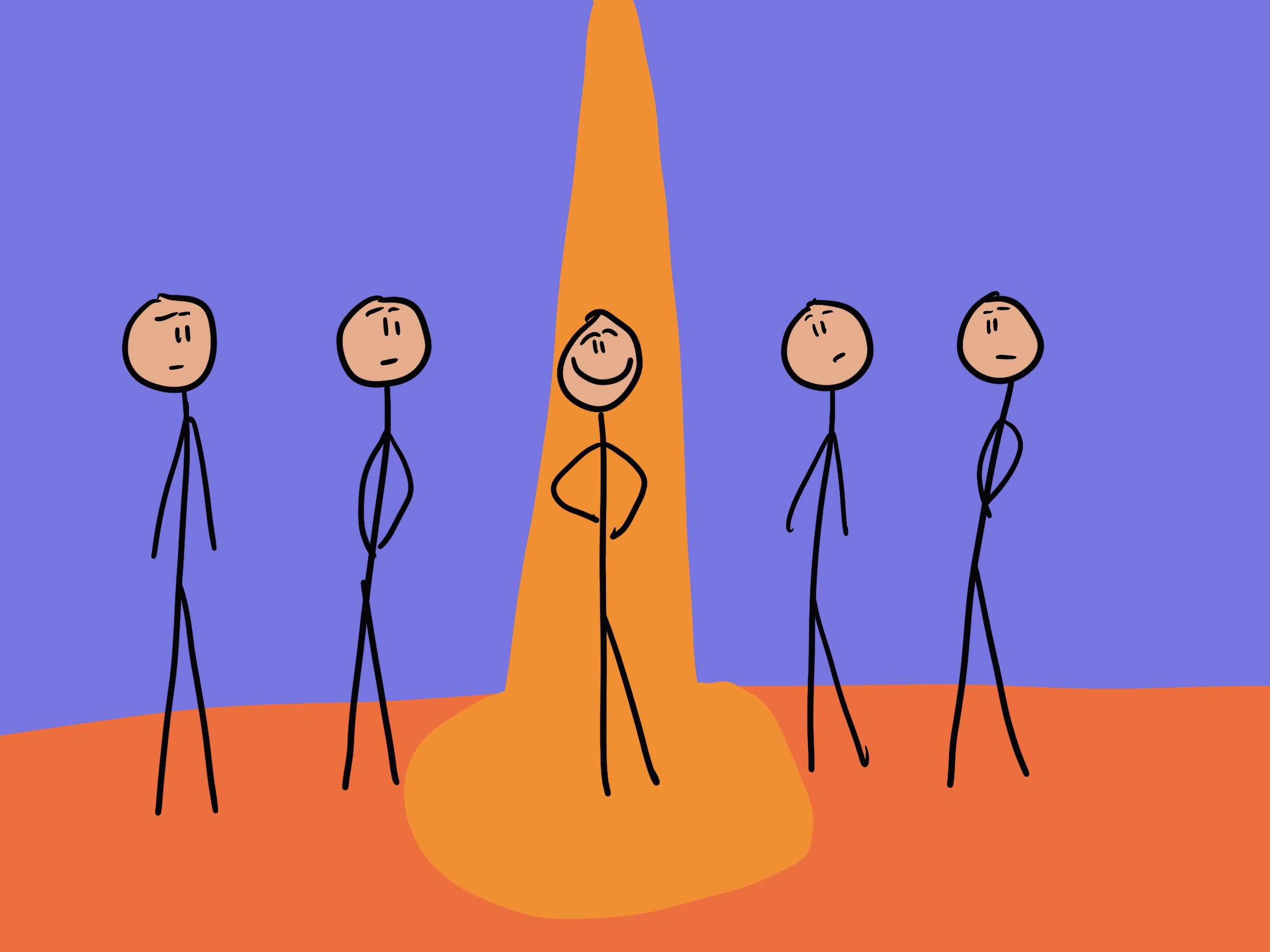

Why do we feel like we stand out more than we really do?

The Spotlight Effect

, explained.What is the Spotlight Effect?

The spotlight effect describes how people tend to believe that others are paying more attention to them than they actually are—in other words, our tendency to always feel like we are “in the spotlight.” This bias shows up frequently in our day-to-day lives, both in positive situations (like when we nail a presentation and overestimate how impressed all our co-workers must be) and in negative ones (like when we bomb the presentation and feel like everybody must be laughing about it behind our backs).

Where this bias occurs

Let’s say you go to a party at your friend’s house, and you end up spilling some of your drink on your shirt. As you make your way to the bathroom to clean yourself up, you feel like everybody at the party is watching you make a fool of yourself, and you’re incredibly embarrassed. However, a few weeks after the party, when you bring it up with your friends, nobody else even remembers the incident.

Debias Your Organization

Most of us work & live in environments that aren’t optimized for solid decision-making. We work with organizations of all kinds to identify sources of cognitive bias & develop tailored solutions.

Individual effects

The spotlight effect causes us to have an exaggerated view of our own significance to the people around us, leading us to misjudge situations and make decisions based on our overly inflated feelings of visibility.

Systemic effects

The belief that others are always paying close attention to us can be harmful to our mental health, and it can hold us back by making us feel self-conscious. If we continuously fall into the trap of the spotlight effect, we might pass up opportunities based on a mistaken assumption that others will analyze and judge us for them. The spotlight effect can also contribute to social anxiety, which has many detrimental effects on a person’s physical and mental health.1 Trying to change the belief that others are constantly watching and thinking about us is an important part of treatment for anxiety.

Why it happens

The spotlight effect is just one example of a type of cognitive distortions known as egocentric biases. This type of cognitive bias skews the way we see things by causing us to rely too heavily on our own perspectives, rather than adjusting to take other viewpoints into account. Another common example of an egocentric bias is the false consensus effect, which causes us to assume that most other people share the same beliefs and opinions that we do.2 There’s also the illusion of transparency, describes how people tend to believe that others are able to discern what we’re thinking or feeling.6

In a way, in our daily lives, all of us play the role of an amateur social psychologist: we are constantly trying to figure out why other people act the way they do. However, as the many egocentric biases demonstrate, we also have a tendency to center ourselves, even if we’re not trying to—after all, the only point of view that we have direct access to is our own. This means that our interpretation of a situation comes filtered through our own thoughts and emotions.

Our judgments are anchored by our own experiences

In part, the spotlight effect is driven by another cognitive bias, known as anchoring (or the anchoring bias). First coined by Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman, two of the “founding fathers” of behavioral economics, anchoring describes how when we are making decisions, we tend to rely too heavily on information that we received early on in the process.3 Once we make a plan or estimate based on this early information, we start to think about everything that happens next in terms of that initial value. This makes us resistant to making major changes to our plan, even if the situation calls for it.

The effects of anchoring are so strong that we can even become anchored to information that’s not relevant to our goals. For example, in one experiment, people were asked to provide the last two digits of their social security number. They were then shown a number of products one at a time, including objects like computer equipment, bottles of wine, books, and boxes of chocolate. For each item, participants were asked if they would be willing to pay the amount that their two social security digits formed. For example, if somebody’s number ended in 34, they would say whether or not they would pay $34 for each item. After that, the researchers asked what the maximum amount was that the participants would be willing to pay.

This study found that, even though the social security number is just a random string of numerals, people still became “anchored” to the amount these digits formed. Those who had higher numbers were willing to pay much more for the same products, compared to others who happened to have lower numbers.4 As this experiment shows, any information we receive at the start of our decision making process becomes our point of reference for future decisions, even if this is illogical or puts us at a disadvantage.

So, what does this have to do with the spotlight effect? Well, one way to explain this bias is as a result of anchoring. When we are making judgments about social situations, we become anchored to our own perceptions, because they are the only thing we have immediate access to. Afterwards, we may try to adjust our views to take other people’s perspectives into account, but because of anchoring, these changes are insufficient.5

There is some experimental evidence to back up this theory. In the first paper on the spotlight effect, published by Thomas Gilovich, Victoria Husted Medvec, and Kenneth Savitsky researchers elicited the spotlight effect in their participants by putting them in a situation that most college students at the time (that is to say, the late 1990s) would find embarrassing: being forced to wear a T-shirt featuring everyone’s favorite one-hit wonder, Vanilla Ice, singer of “Ice Ice Baby.” (An earlier version of the experiment involved T-shirts with the face of singer Barry Manilow.) The participants were then briefly brought into a room where a few other students were working, after which they answered some questions from the researchers.

Gilovich, Husted Medvec, and Savitsky had already shown (through the Barry Manilow shirt study and others) that participants significantly overestimated how many of the other students would be able to recall what was pictured on their shirt. This is the spotlight effect at work: the T-shirt wearers, feeling embarrassed about their outfit, felt that people were paying more attention to them than they really were. But in the Vanilla Ice version of the experiment, the researchers went a step further: they also asked participants whether or not they had considered any other numbers before deciding.

A majority of the participants also said that they had initially considered a higher number, before adjusting downwards. This is in line with what we would expect if anchoring were at play: people initially came up with an extra high estimate, and then dialled it back a little bit—but not enough, because their perception was influenced by their original guess.

We notice changes in our behavior or appearance more than others do

Another reason that the spotlight effect might happen is that we are more familiar with our own behavior and appearance than other people are, and so we are more aware when there is something “off” about it. Everyone has had “bad hair days,” for instance, or mornings where they’ve woken up to find an angry, red pimple on their face. Or, to give a non-beauty-related example, academics who give the same talk over and over again might feel like they do a great job on some days and a terrible job on others, and be surprised to find that they get a similar response from their audience regardless.5

When we do something out-of-the-ordinary or perceive a change in our own appearance, it feels like everybody else must be just as fixated on it as we are—but they’re not. Research has confirmed that we tend to overestimate how much other people notice variations in the way we act or look. In one study, college students were asked to rate, on a 7-point scale, how they thought they appeared to everyone else on that particular day, relative to their appearance on most days. The gap between these two estimates was much larger than the actual ratings that other people gave of them.5 This can also drive the spotlight effect, in cases where we are self-conscious because something’s different from normal.

Why it is important

As mentioned above, the spotlight effect can contribute to social anxiety, which has consequences for our social lives as well as our overall health. It can also cause us to make decisions based on the incorrect assumption that we are being constantly sized up by other people. The reality, for better or worse, is that people often don’t notice or care about things we are highly conscious of ourselves. Thinking otherwise can cost us opportunities and negatively affect our relationships with other people. However, once we’re aware of this bias, we can take steps to overcome it.

How to avoid it

For better or worse, the truth is that other people almost never care about us as much as we think they do. Sometimes, just reminding oneself of this fact can be enough to counteract the spotlight effect. But if that’s not enough, try some of these tips.

Ask yourself how you’d react if the roles were reversed

If you find yourself worrying all day about a mistake you made during a presentation, or the bit of spinach stuck in your teeth that a coworker had to point out to you, try to take a moment to consider how you would feel if you were on the other side of this interaction. In fact, on many occasions, you’ve probably been in the audience of a talk where the presenter fumbled their words a bit, or whispered to a pal that they should check their teeth in the bathroom—but these episodes probably didn’t register very much, because you don’t think anything of them at the time. This is probably also true for the people who have now witnessed your slip-up: it may feel like the end of the world to you, but others may not even give it a second thought. This is a simple way to calm down and comfort yourself when you’re caught up in anxiety due to the spotlight effect.

Try some cognitive restructuring

A slightly more hands-on method to deal with biases like the spotlight effect comes from cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), which is often used to treat anxiety. One staple of CBT is the use of worksheets, where clients work through distressing thoughts (either on their own or with the help of a therapist) by challenging any cognitive biases or distortions that might be causing anxiety. This process is known as cognitive restructuring.

In the case of the spotlight effect, there are some worksheets (like this one) that prompt people to think about the evidence that supports the thought that’s causing anxiety, as well as the evidence that does not support it. The final step is usually to come up with an alternative, or “balanced” version of the thought. For example, if somebody says something incorrect during a conversation, and the spotlight effect causes them to think “Now everybody must be talking about how I’m stupid,” a more balanced thought might be something like “Other people might have noticed my mistake, but they probably didn’t think much of it afterwards.”

How it all started

Gilovich, Husted Medvec, and Savitsky coined the spotlight effect in a paper published in 2000. This paper talked about five separate experiments the authors conducted, including the ones with the Barry Manilow/Vanilla Ice T-shirts described above. In one of the other experiments, the researchers used T-shirts that college students were more likely to rate as appealing (in the late 90s, this meant T-shirts featuring Jerry Seinfeld, Bob Marley, or Martin Luther King Jr.) in order to demonstrate that the spotlight effect happened in positive situations as well as negative ones.

At that point, they had recently published their work on the illusion of transparency (which they also coined). The spotlight effect is closely related to the illusion of transparency, and they argued that both resulted from anchoring. Overall, this team of researchers has made many important contributions to the literature on egocentric biases.

Example 1 - The minority spotlight effect

Everybody is susceptible to the spotlight effect. However, people who belong to a minority group might also feel “in the spotlight” when topics related to their group come up in conversation.

In a study on this “minority spotlight effect,” participants (some white, some belonging to an ethnic minority) were brought into a room where two other people were waiting. These people were confederates, meaning that they were “in on” the experiment and were working with the experimenter. All three put on headphones and listened to a recording. Participants heard about either carbon emissions (the control condition) or affirmative action, an issue that is related to race. Meanwhile, the confederates heard instructions that told them where to look, and when. Sometimes they were told to simply look up, while other times they were told to look at the participant.

The results showed that minority participants who listened to the affirmative action tape felt like the confederates had stared at them significantly more than the other groups, even though they had actually looked at everybody for the exact same amount of time. This group also said they felt more “in the spotlight,” and experienced more negative emotions than others. This might happen because people of color are used to being put on the spot when the topic of race comes up, leading them to feel uncomfortable in anticipation of this happening again.7

Example 2 - Alone in the spotlight

In our culture, there’s often a stigma attached to doing things alone, whether it’s travelling or just going out to lunch at a restaurant—so much so that the latter was once used as subplot fodder for an episode of Friends. (Monica: “Excuse me, what is wrong with a woman eating alone?” Chandler: “Well, obviously something. She’s eating alone!”)

In reality, most people are unlikely to notice or care about other people doing stuff solo. But the spotlight effect creates a self-fulfilling prophecy here: people feel anxious about going out alone, and then this cognitive bias causes them to believe that other people are paying more attention to them than they actually are, confirming their anxiety. Thankfully, the taboo seems to be loosening up as of late, as more people feel emboldened enough to venture out unaccompanied.8

Summary

What it is

The spotlight effect is a bias that causes us to feel like other people are more focused on us than they really are.

Why it happens

We are prone to egocentric biases, which lead us to center our own perspective while ignoring others. The anchoring effect makes it difficult for us to adjust our perceptions of things. The spotlight effect can also occur because we are more familiar with ourselves than others are, meaning we are more aware of changes or variations.

Example 1 - The minority spotlight effect

Research shows that members of minority groups experience something very similar to the spotlight effect whenever topics related to their group come in conversation. This experience is uncomfortable and unpleasant.

Example 2 - Alone in the spotlight

Because of the spotlight effect, many people feel uncomfortable doing things alone in public. Luckily, this is starting to change.

How to avoid it

If you’re feeling “in the spotlight,” try reminding yourself that most people simply aren’t as focused on your behavior as you are. You can also imagine how you’d feel if the roles were reversed. If the spotlight effect is driving more severe or pervasive anxiety, it might be worth trying some exercises from cognitive behavioral therapy (ideally with a clinician).

Related TDL articles

Watch Out For These Cognitive Biases When Working From Home

In this age of digital communication and weird new diseases, working from home is increasingly common. Like anything, this comes with pros and cons. One possible drawback of working from home is that it can make certain cognitive biases more prominent, possibly affecting decision making. This article discusses how the spotlight effect is relevant to remote work, and gives some tips on how to avoid it.

Does Anchoring Work In The Courtroom?

The spotlight effect is largely driven by anchoring, one of the most pervasive cognitive biases. This article digs into another area where anchoring might cause (even more serious) problems: the courtroom. Looking at experimental evidence, the author discusses whether or not anchoring can bias the decisions of judges and juries alike. (Spoiler alert: It can.)