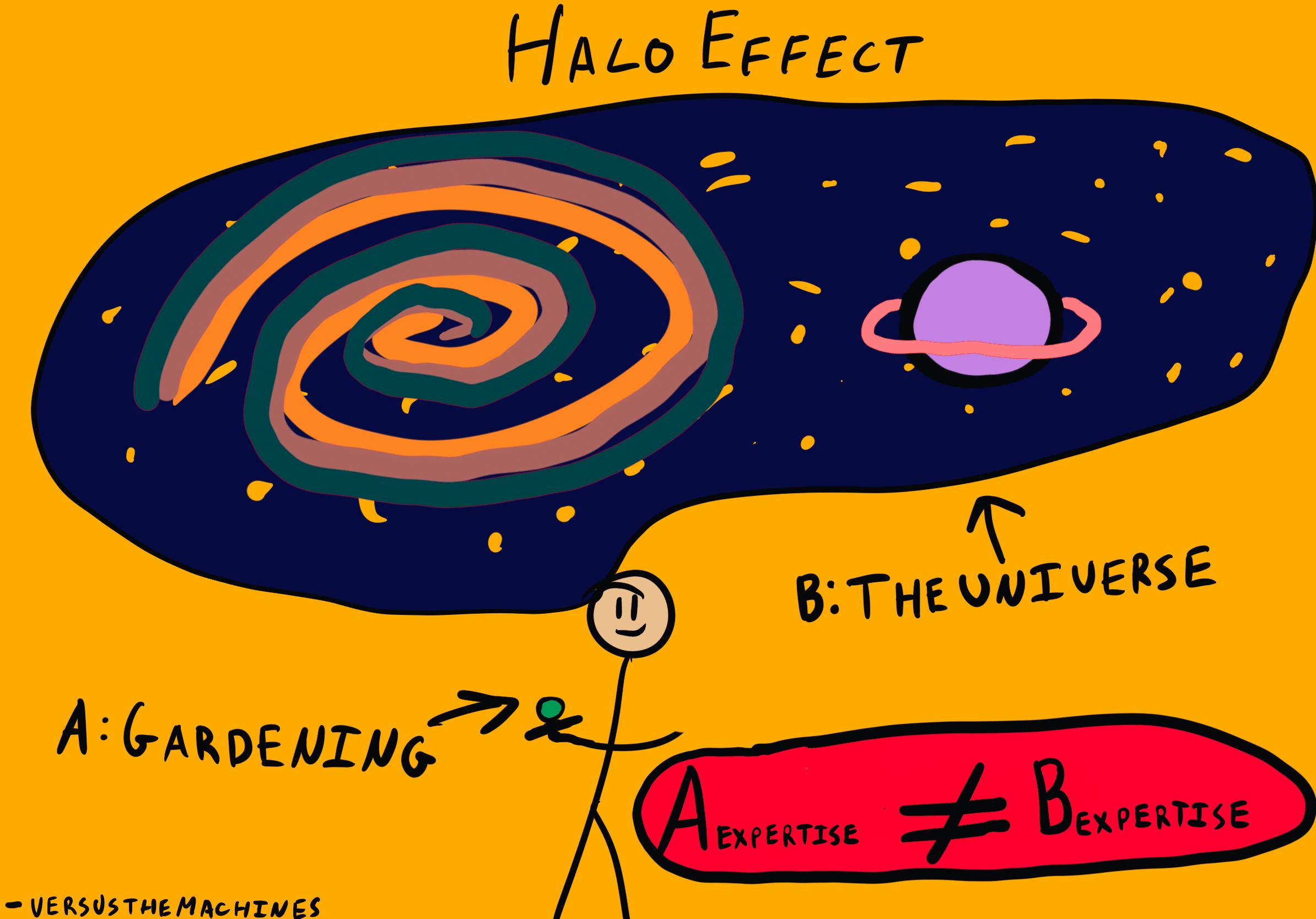

Why do positive impressions produced in one area positively influence our opinions in another area?

Halo Effect

, explained.What is the Halo Effect?

The halo effect is a cognitive bias that claims that positive impressions of people, brands, and products in one area positively influence our feelings in another area.

Where this bias occurs

The halo effect often occurs when we consider appearances. A classic example is when one assumes that a physically attractive individual is likely to also be kind, intelligent, and sociable. We are inclined to attribute positive characteristics to this attractive person even if we have never interacted with them. The halo effect is an error in our judgment and reflects individual preferences, prejudices, and social perception.

While biases can create an impact on an entire group, the halo effect can also be individualized. For example, if you specifically value one brand of hair care products, you may be likely to evaluate their new line as amazing, even if it has terrible reviews.

Debias Your Organization

Most of us work & live in environments that aren’t optimized for solid decision-making. We work with organizations of all kinds to identify sources of cognitive bias & develop tailored solutions.

Related Biases

Individual effects

We can find this bias in all aspects of our life, from interactions at school and in the workplace, to responses to marketing campaigns. When the halo effect takes hold of our decision-making and appraisals, it can hinder our ability to think critically about other peoples’ traits. As a result, we may overlook or disregard certain obvious flaws in both people and products. This skewed perception can lead to us making inaccurate character assessments, or even causing us to miss out on valuable opportunities.

This effect can lead to another potentially harmful mental shortcut, confirmation bias. While the halo effect informs our immediate perceptions of a person or product confirmation bias is what keeps those impressions long lasting. Correspondingly, we seek out information to affirm what we already believe creating an echo-chamber of our inaccurate evaluations.

Systemic effects

Aside from its negative impact on our individual lives, the halo effect can add up to create systemic challenges. One example of this can be seen in the psychology behind consumer habits. Studies have shown that when the same food products are labeled either “organic” or “conventional” the “organic” products receive higher ratings and consumers are willing to pay a higher price for them.1 This demonstrates how consumers can be manipulated to spend more money than necessary.

Unfortunately, the halo effect can play a large role in the workplace. Research suggests that race, attractiveness and gender all impact the likelihood of positive or negative evaluation at work. In a meta-analysis comprised of two studies, researchers Xu, Martinez, and Smith found that conventionally attractive people who worked service jobs (ex: hotel customer service, restaurant staff) were rated higher by their customers compared to other employees.8 While the awareness that attractiveness plays a role in global evaluations has been documented since the 1950s, exploring how this may create profound inequality in various domains illuminates the pervasive nature of the halo effect. In favoring others on the basis of outward appearance we are prone to making uninformed decisions and can miss out on quality employees, political candidates, and products.

However, the halo effect is not limited to groceries and the workplace. Zooming out, we can see how the halo effect can alter our decision making on everything from politicians to cereal brands. While this effect may not pose a threat in all sectors, it is important to be aware of our bias so as to not fall into the trap of stereotyping, or, put classically, “judging a book by its cover.”

How it affects product

Given that the halo effect has a lot to do with appearance it is heavily linked with product and branding. Firstly, people tend to stick with products that they have already judged to be good. For instance, it is rare that someone uses different brands of technology for their phone, computer, and watch. Typically, once we show loyalty to a brand, it earns that golden halo, making it harder for us to consider alternatives.

Marketing is where companies can really take advantage of the halo effect. By hiring specific public figures to promote their product they may reach a wider audience who will make positive evaluations of the brand. However, not only do recognizable faces sell products, but those who are conventionally attractive will also promote flattering judgements about a given item. For example, if you are in the market for a new pair of running shoes you may favor the brand who features healthy and fit individuals alongside star athletes.

However, good marketing doesn’t always equate to a good product, and in the age of social media, we are flooded with various campaigns all trying to make a unique impression. It is important to slow down in our decision-making in order to be less easily influenced.

The halo effect and AI

If done properly, artificial intelligence can actually help to mitigate the halo effect. To illustrate, certain companies implement AI software to scan job applications and weed out potential candidates from those who may not be qualified. Filtering out certain, bias triggering, information and evaluating based on defined job criteria can help to eliminate human error and the tendency toward the halo effect.6 For example, if a particular manager completed their schooling at X university, they may think that others who attended this university share his values and may be biased to believe that they will be the best fit for the role.

It is important to remember that AI software is not completely bias free. Everything from the data it uses to make predictions to the programmers who create the systems can cause biased output. However, this too can be fixed, it is a lot easier to point out bias when we are not the ones perpetrating it. If we catch a system following that same human pattern we can address and correct it.

Why it happens

The halo effect occurs because human social perception is a constructive process. When we form impressions of others, we do not rely solely on objective information; instead, we actively construct an image that fits in with what we already know. Indeed, the fact that we sometimes judge another person’s personality based on their physical attractiveness seems incorrect, but research continues to demonstrate the effect.

The Term ‘Halo’

The halo effect is named in connection with the religious symbol. Crowing the heads of saints, a glowing halo bathes their faces in light. Fittingly, the halo effect causes us to think highly of people, often due to their outward appearance, or based on one quality that we value.

Role of Attractiveness

While there are a number of factors that can influence the halo effect, a person’s attractiveness is among the most common characteristics to produce cognitive bias. Research has revealed that attractiveness may affect perceptions tied to life success and personality.2 This suggests that evaluations pertaining to attractiveness may influence evaluations for a number of other traits, providing evidence for the halo effect.

Why it is important

Being aware of the halo effect can help us understand how it affects our lives. Whether you are trying to evaluate another person, deciding which political candidate to vote for, or choosing which movie to watch, you should consider how your impressions might affect your evaluations. Though being aware of the halo effect does not eliminate the bias from our lives, it can certainly help to improve our objective decision-making abilities.

When we are making decisions too quickly, or with minimal consideration, the halo effect (amongst other cognitive biases) takes over. When this happens we are less likely to pay attention to contradicting information, and default to information that confirms what we believe is true. The halo effect causes poor decision-making, but more seriously, can lead to prejudice. For instance, if we believe that Ivy League schools produce the most qualified employees, we may have a bias in the interview and view the individual as a perfect fit even if there is an even better candidate who did not attend one of those schools.

How to avoid it

While the halo effect may seem like an abstract concept that is hard to actively notice, there are many ways we can attempt to avoid the bias.

Cognitive Debiasing

To minimize the influence of the halo effect, one can look to various cognitive debiasing techniques such as slowing down one’s reasoning process. For example, if you are aware of the halo effect, you can mitigate the bias by trying to discourage character judgments when first meeting someone. Remind yourself that once we gain more information about the person, we can get a more accurate image of who they are. Another tip would be to reduce comparison. When meeting someone, we should try to let them show us who they are, rather than pushing them in a box just because they bear some resemblance to an existing schema.

The halo effect is not solely limited to the way we look at other people. It can also play a role in how we judge things such as products and brands. For example, if you have a positive impression of a certain brand, you will be more likely to buy products from that brand, even if your impression has no relation to the product’s quality. You should always consider the bias when purchasing products because the highest quality brand, or the best brand for you, may not be the most popular or heavily advertised.

The Horns Effect

Although we should maintain an awareness of the halo effect, we should also look out for when the bias works in reverse—a psychological process called the horns effect. This cognitive bias causes our negative impression of someone or something in one area to change our impression of them in other areas. For example, if someone does not like the way a product looks, they will not buy the product despite the potential benefit that it could bring them.

How it all started

The halo effect has had a long history, and was illustrated long before it got its name.4 In a study conducted in 1907 on the literary merit of authors, Frederick L. Wells had individuals of varying levels of knowledge rank the most prominent authors of the time demonstrated how the overall perceptions of the authors impacted the rankings for some participants.7 However, it’s first explicit demonstration was lead by American psychologist Edward Thorndike in 1920.

The study, “a constant error in psychological ratings,” looked at how commanding officers ranked their soldiers on levels of intelligence, technical skill, and reliability. It also examined commanding officers’ evaluations on leadership as well as personal qualities. Thorndike found that the commanding officers’ judgment was colored by their general feeling about each individual soldier. In other words, the commanding officers based their technical assessments on whether or not they believed the soldier to be a good person in general. After replicating these findings in subsequent studies, Thorndike was able to conclude that people are unable to separate their overall general assessments from numerous other characteristics. As a result, an error of judgment emerges that leads people to make false judgements.3

Example 1 - Diagnosing health problems

Unfortunately, a clear example of the halo effect is in the field of medicine. Physicians may sometimes fall into the trap of judging patients based on their appearance without conducting tests first. Additionally, in terms of mental health, the halo effect can also impact our judgment. We might associate someone with a ‘healthy glow’ as someone who is healthy. However, this person could be suffering from a mental illness that cannot be understood without additional conversation and testing. Indeed, some studies have gone so far as to suggest that “attractiveness suppresses the accurate recognition of health.”4

Example 2 - Assessment in school

Another example of the halo effect can be seen in education. There is some evidence to suggest that perceived attractiveness can lead to higher grades in school, although there is also evidence suggesting the contrary. Other research has linked name recognition to higher grades in school. A study by H. Harari and J. W. McDavid predicted that teachers’ evaluations of children’s performance would be associated with stereotyped perceptions of the students’ first names. Short essays written by 5th-grade students were evaluated by teachers for the study. The names of the children, however, were replaced by some popular and“attractive” names while others were replaced with rare and “unattractive” names. Overall, the study found that the essays with names that were associated with positive stereotypes received the highest grades. This goes to show that even experienced teachers fall into the halo effect’s trap, leading their preconceived judgments to obscure their grading.9

Summary

What it is

The halo effect occurs when our positive impressions of people, brands, and products in one area lead us to have positive feelings in another area. This cognitive bias leads us to often cast judgment without having a reason.

Why it happens

The halo effect occurs because human social perception is a constructive process. When we form impressions of others, we do not solely rely on objective information, but we actively construct an image that fits in with what we already know. As a result, our general perceptions of people and things skew our ability to make judgments on other characteristics.

Example #1 - Diagnosing health problems

One example of the halo effect can be found in the field of medicine. Doctors can sometimes assume a patient is healthy because that person appears ‘healthy.’ However, without additional tests, the doctor cannot know for sure that the patient is completely healthy.

Example #2 - Assessment in school

A second example of the halo effect can be seen in education. Research has shown that students with the most attractive physical qualities or the most attractive names receive the highest grades. Even when teachers are experienced, they may still fall into this cognitive trap.

How to avoid it

To minimize the likelihood that you will be influenced by the halo effect, you can look to various cognitive debiasing techniques such as slowing down your reasoning process. For example, it is a good idea to avoid drawing conclusions about someone upon first meeting. Over time, you will be more accurate in your perceptions and be in a better place to make a character judgment.

Related Articles

The Halo Effect in Consumer Perception: Why Small Details Can Make a Big Difference

This article considers how the halo effect can change consumer perception. When creating products, companies should keep in mind that the smallest attribute of a product can change consumers’ perceptions. Similarly, the halo effect can play a role at the brand level where consumers’ perceptions of a certain aspect of a company can lead them to buy more or fewer products.