How Does Society Influence One's Behavior?

Behavioral economics and nudge theory gets a bad reputation. Sometimes vilified as dark marketing, government interference, or self-serving paternalism, fears arise around the notion that such interventions infringe on individual rights.

Yet, the fact is that we very rarely make choices in isolation of outside influences.

"We are social beings, and thus, our choices are made in the context of social connections, personal relationships, and physical environments — all of which will have been influenced by other people."

Indeed, the very concept of behaviorally-influenced public policies, and the extent to which these can be effective, demonstrates how individuals respond to outside agency. Behavioral economics harnesses these human insights, and works on the premise that — both to help people individually and to have a positive impact on the widest number of people — individuals’ behavior can be influenced without restricting their liberties.

For example, when it comes to taxes on alcohol or sugar consumption, some argue that their body is their own, and thus they should be left to make their own decisions. To be sure, public health policy aims to provide the individuals with the utmost freedom in cases where the negative consequences of their behaviors can be internalized. However, it also holds that if there are externalities, or public costs, to these behaviors (as there often are), the government is justified in campaigning to reduce the incidence of such behaviors. Thus, it is not only that social forces influence our behaviors, but that, in turn, our behaviors impact societal outcomes.

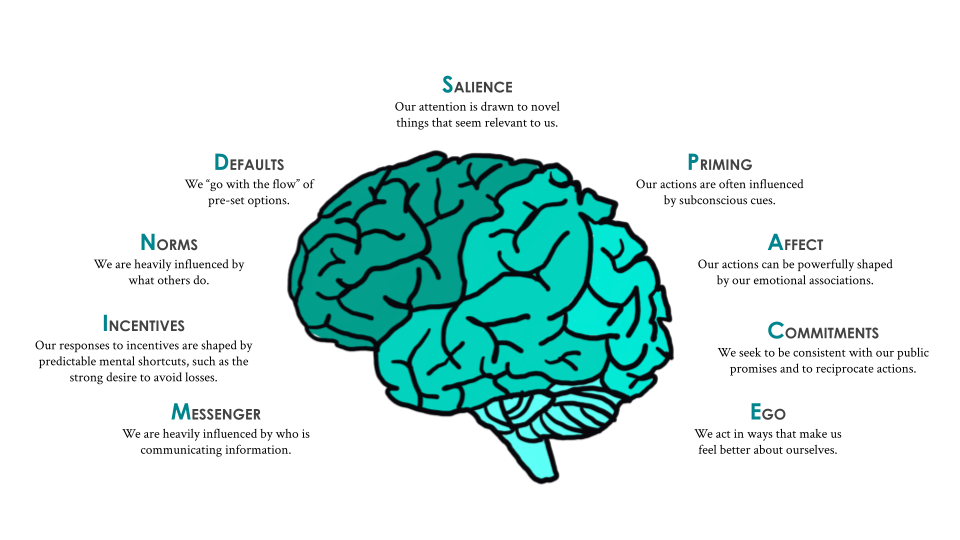

The UK’s Behavioral Insights Team (BIT) use the framework MINDSPACE to aid the application of behavioral science to the policymaking process. They argue that the ideas captured in the mnemonic are ‘nine of the most robust influences on our behavior.’ These are as follows:

Whether it is acting in line with social norms, seeking ways to act that make us look good to others, or relying on category and perception to form our opinions of those with whom we interact, it is clear that these social components have an outsized impact on our individual behaviors. Let’s look at a few examples:

Behavioral Science, Democratized

We make 35,000 decisions each day, often in environments that aren’t conducive to making sound choices.

At TDL, we work with organizations in the public and private sectors—from new startups, to governments, to established players like the Gates Foundation—to debias decision-making and create better outcomes for everyone.

Messenger – interaction with others

In another classic example, the UK’s BIT worked with HMRC (the UK’s tax collection agency) to increase tax payments by sending out reminder letters stating that most people in the recipient’s area had paid their tax. The impetus for this intervention is the simple insight that no one wants to be the naughty individual in their community, and that reframing tax payment as not only a legal obligation but a social norm would increase compliance. The letters emphasizing the positive social norms produced a 15% higher response rate than the standard letter, and it has been estimated that if the approach was taken across the country, it could help to collect £160m extra tax revenues per year.

Norms – peer pressure

In another classic example, the UK’s BIT worked with HMRC (the UK’s tax collection agency) to increase tax payments by sending out reminder letters stating that most people in the recipient’s area had paid their tax. The impetus for this intervention is the simple insight that no one wants to be the naughty individual in their community, and that reframing tax payment as not only a legal obligation but a social norm would increase compliance. The letters emphasizing the positive social norms produced a 15% higher response rate than the standard letter, and it has been estimated that if the approach was taken across the country, it could help to collect £160m extra tax revenues per year.

Commitment – a public declaration

Similarly, facilitating the creation of social norms is part of UNICEF’s approach to challenging the practice of female genital mutilation (FGM) in some African villages. According to the NGO Tostan, a key factor leading to the abandonment of the practice was addressing collective rather than individual behaviors. Public condemnation of FGM and declarations against it were found to have a significant symbolic value.

The AI Governance Challenge

Defaults – tipping point

The Social Cognitive Networks Academic Research Center (SCNARC) analysed vast quantities of data to identify the tipping point at which a marginal belief becomes the majority opinion. Their estimate suggests that at least 10% of people have to hold an opinion for it to have a chance of being adopted more widely. Thus, they argue, a small group can create change — so long as they are committed and consistent in their belief. Perhaps the most effective way to achieve widespread modification of behavior is to reach those 10%. If word of mouth is the best form of advertising, obvious and clear actions could be the best form of encouraging social change.

What these results all suggest is that, though we like to think of our choices as our own, in fact, they are often profoundly impacted by the choices and views of our peers. In that way, John Donne was right — no man is an island. Especially when it comes to behavior.

About the Author

Francesca Baker-Brooker

Francesca Baker is fascinated by people, and their experience of the world. A researcher with 9 years’ experience, she is highly curious, and combines this with a sense of creativity and communication skills to explore the world and tell the stories that matter.