Putting the ‘Architect’ in ‘Choice Architect’: Behavioral Science in University Building Design

A frequently encountered term in behavioral science is “choice architecture.” It suggests that choices are not made in a vacuum but are dependent on the environment—both physical and abstract. Candy specifically positioned in the checkout aisle will cause tired, hangry kids to throw tantrums, while exhausted parents give in and buy “just that one chocolate bar.” The choice to become an organ donor depends on a more abstract choice environment, what’s the default? Is there a forced decision point (e.g. when getting your driver’s license)? Much like how an architect chooses the material, shapes, colors, and layout of a physical space, choice architects design our decision-making environments.

Perhaps without realizing it, architects are also choice architects. The design elements of a building wield significant influence over the behaviors that unfold within it. Ultimately, leveraging this effect is crucial in designing successful buildings.

What is a successful building, anyway?

The key performance indicators (KPIs) that architects and designers are (traditionally) chiefly concerned with when evaluating a building include:1

- Energy efficiency (e.g. energy consumption)

- Indoor comfort (e.g., thermal comfort, air quality)

- Technical building performance (e.g., ventilation heat losses)

- Environmental factors (e.g., carbon absorption by trees)

- Economic factors (e.g., construction costs)

- Social factors (e.g. accessibility)

Additional concerns include aesthetics, safety, and general functionality. But these concerns focus on the building independent of the occupants. If you think back to the school you went to as a child, the office you work in now, or a hospital you may have visited, these KPIs lack one fundamental element. Most buildings serve a specific function and would not work well for much outside of that. A good school should look very different from a good hospital wing, a good classroom should not look (and feel) like an office.

The important dimension to consider here is the interaction between the occupants and their built environment. More specifically, we consider the influence that the building design has on peoples’ behavior, mood, productivity, social life, and ultimately, their physical and mental health. Especially in buildings with occupants that have diverse needs, such as students in their school or patients in a hospital. Taking a holistic view of the effect the built environment has on their behaviors and well-being is particularly important.

Behavioral Science, Democratized

We make 35,000 decisions each day, often in environments that aren’t conducive to making sound choices.

At TDL, we work with organizations in the public and private sectors—from new startups, to governments, to established players like the Gates Foundation—to debias decision-making and create better outcomes for everyone.

Creating the built environment for university students to thrive

From 2023 to 2024, The Decision Lab collaborated with an Ivy League university to assess how their buildings impact students' behavior, emotional well-being, and educational outcomes during their time living on campus. Partnering with an architecture firm, an organization specializing in system design, and a building consultancy, TDL evaluated the performance of a library and four dorm buildings, asking questions like: How are students using the different spaces? Do the common rooms actually contribute to socialization? Where do students go to study and relax, and why?

The ultimate goal was to develop a process for the university to evaluate its buildings along two dimensions. First, the traditional parameters of physical building performance and user comfort. Second, the building’s ability to create an inclusive environment, foster a sense of belonging, and promote individual and collaborative learning. In addition, we hoped to uncover general lessons to inform the design of future buildings and to actively address these factors in early planning stages.

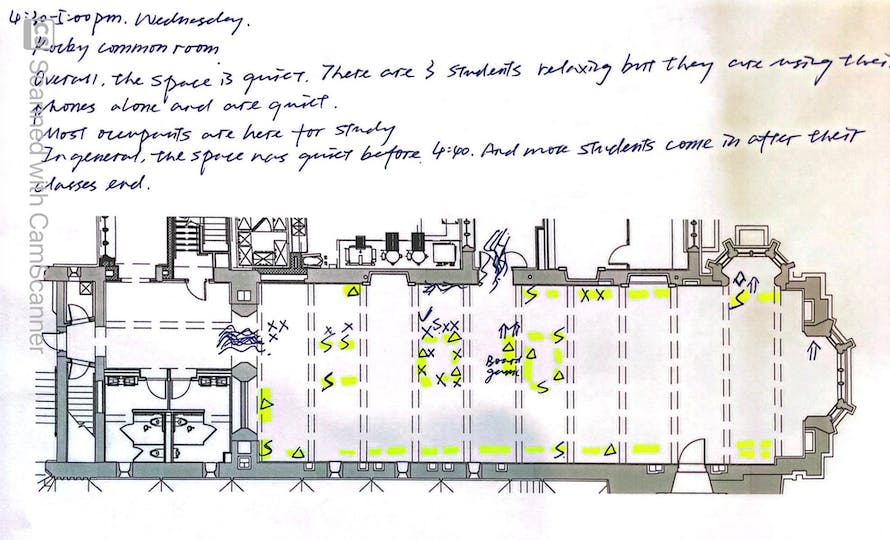

Applying a mix of quantitative survey-based research methods, qualitative interviews, focus groups, and behavioral mapping exercises, we evaluated the interaction of students with their built environment.

Let’s dive into three of the most interesting insights.

1. Nowhere to hide—feeling the need to (appear to) study in all university spaces

While the university provides students with spaces to relax and unwind, such as coffee shops or common rooms with recreational equipment like pool tables, TVs and board games, students are facing a strong bias in how they perceive these spaces.

Interviews consistently uncovered that students felt compelled to work and study in all spaces “provided by the university.” Students would have their laptops open and their notes out even while having coffee with friends or socializing in the common rooms. A mix of peer pressure, fear of judgment, perceived obligations towards the University (and those funding the tuition costs), and personal motivation prevented students from seeing the university-offered recreational spaces as genuine opportunities to relax.

Unsurprisingly, this was most true for the library: while the building boasted a coffee shop, lounge areas, and access to green spaces, students consistently reported viewing the library only as a place to study. In addition, many felt spotlighted when they weren’t actively working. While this omnipresent expectation was motivating to some students and helped them focus, it also took a toll on the mental well-being of others, who reported feeling anxious, stressed and judged.

So how can building design address this? Rather than providing additional recreational spaces, the university is better advised to create more “student-owned spaces.”

These are spaces that feel like they are run for students, by students and are outside the official university jurisdiction. Students are responsible for the design, operation and maintenance. They are allowed to leave their mark and customize the space as they see fit. This can take various forms, such as a student-run café, bar, community center, or even just a quiet space where students can engage in their artistic and creative pursuits.

The important aspect is the shift in ownership and responsibility coupled with the physical and visual distinction from the rest of the university. This provides the opportunity to take a break from work and study, as well as from feeling watched and judged.

2. Cozy lounge or grand gothic halls—what makes a good common room?

In the quest to create communal relaxation spaces that truly meet the needs of a diverse student body, one element to grapple with is the design of common rooms.

The common rooms in our project were frequently observed to serve as quiet study spaces rather than the bustling social hubs they were meant to be. Their interior design ranged from grand gothic halls with high ceilings and heavy armchairs to smaller spaces with the ambience of a coffee shop. We found that the construction and design elements were paramount to their success.

First, the strategic placement within the building plays a crucial role. Proximity to elevators or the dining hall with lots of traffic during certain hours helps to create a lively and more vibrant atmosphere conducive to socialization and spontaneous encounters.

Second, the design and arrangement of furniture influence the use of the space. Furniture that is modular and lightweight invites social interaction. Customizable seating arrangements can be adapted to fit the needs of each group coming in, such as providing the flexibility for others to join. In contrast, large and heavy couches or armchairs, even if they are viewed as cozy, generate rigid set-ups that do not lend themselves to this kind of customization. Similarly, providing variety in the available furniture, such as tables of different shapes and sizes and a mix of chairs and couches, can boost a common room’s usability as a social space.

Finally, the acoustics are vital. Common rooms are meant to be used by several groups simultaneously. These groups need to feel like they can talk without being overheard. In addition, echoey spaces, where sounds reverberate and amplify, can cause too much noise pollution when several conversations happen simultaneously.

3. Old vs. New—feeling connected to the past through older buildings

Many newly constructed buildings today, especially universities, are designed with a sleek and modern vibe. Lots of windows and glass, clear lines, light colors, natural materials and spacious open-concept designs. This has several advantages when contrasted with older—especially gothic—brick buildings with labyrinthine corridors.

Modern designs facilitate wayfinding and orientation, and the technical building performance is usually better (e.g. higher energy efficiency, better lighting, ventilation, and temperature control). From the standpoint of the typical building performance KPIs, there is not much to be said for keeping old Gothic structures alive. And yet, from a behavioral perspective (especially at an Ivy), we can reopen the discussion in favour of the grand, classical style.

Many students reported that the gothic buildings make them feel more connected to the past and to the history and traditions of the university. They feel like they are part of something bigger than themselves. This motivates them in their daily studies.

The new dorm buildings, constructed in a modern design, were described as boring or generic, triggering associations with office buildings, industrial buildings, and furniture stores. The atmosphere created by older architecture, juxtaposing a seriousness and feeling of importance with coziness and a sense of belonging, was highly appreciated and conducive to students’ feelings of productivity, motivation, self-worth, and sense of community and belonging. The consideration of this value created by the design and architecture of the older buildings is something the typical success measures would have been sure to miss.

Architect or choice architect?

While this was a specific example, and the findings are unique to this university, we can observe an important lesson: incorporating behavioral considerations into the evaluation and, more importantly, the initial design of the built environment uncovers a rich new layer in the definition of what makes a successful building.

The interactions between occupants and a building should be taken into account and the effects on occupant behavior, mood, and well-being should be considered in building design. Recognizing the impact of building design on occupant behavior can even be intentionally leveraged to ‘nudge’ occupants into, for example, engaging in more sustainable or healthier behaviors. In any case, it’s important to view the ‘architect’ as a true ‘choice architect.’

References

[1] Mosca, F.; Perini, K. Reviewing the Role of Key Performance Indicators in Architectural and Urban Design Practices. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14464. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114464

About the Author

Dr. Clarissa Mang

Clarissa is a consultant at The Decision Lab. She is passionate about bridging the gap between academic research and the practical applications of behavioral science, enhancing the capabilities of policymakers and business leaders to make evidence-based and data-driven decisions. She holds a PhD in Economics from the Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich in Germany. Her research focused on the role of psychological and social constructs in designing successful health and development policies, such as the role of social norms in expanding women’s access to menstrual products in Bangladesh.