Why do we believe misinformation more easily when it’s repeated many times?

The Illusory Truth Effect

, explained.What is the Illusory Truth Effect?

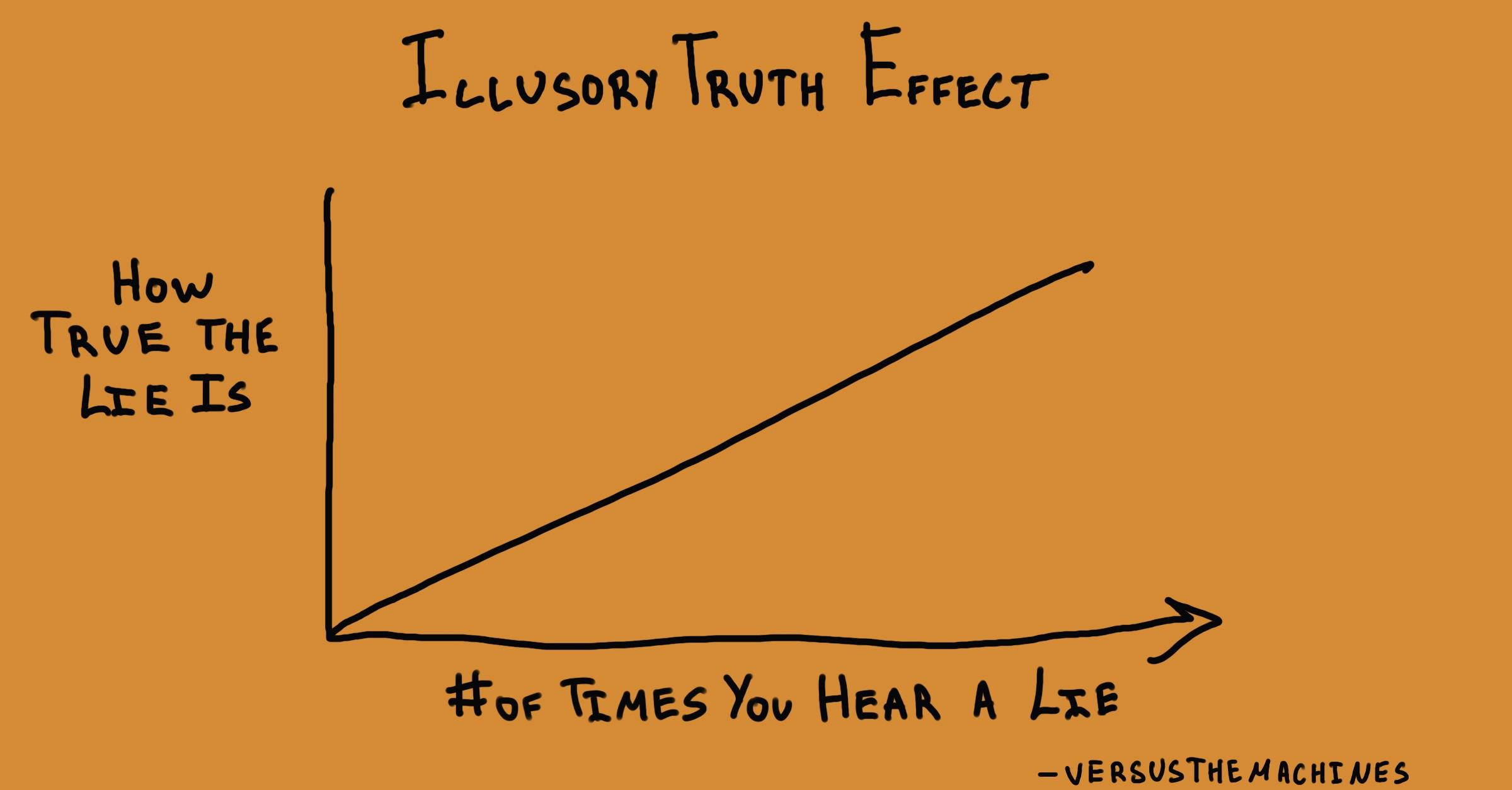

The illusory truth effect, also known as the illusion of truth, describes how when we hear the same false information repeated again and again, we often come to believe it is true. Troublingly, this even happens when people should know better—that is, when people initially know that the misinformation is false.

Where this bias occurs

Imagine there’s been a cold going around your office lately and you really want to avoid getting sick. Over the years, you’ve heard a lot of people say that taking vitamin C can help prevent sickness, so you stock up on some tasty orange-flavored vitamin C gummies.

You later find out that there’s no evidence vitamin C prevents colds (though it might make your colds go away sooner!).18 However, you decide to keep taking the gummies anyways, feeling like they still might have some preventative ability. This is an example of the illusory truth effect, since your repeated exposure to the myth created the gut instinct that it was true.

Debias Your Organization

Most of us work & live in environments that aren’t optimized for solid decision-making. We work with organizations of all kinds to identify sources of cognitive bias & develop tailored solutions.

Related Biases

Individual effects

We all like to think of ourselves as being impervious to misinformation, but even the most well-informed individuals are still prone to the illusory truth effect. We may be skeptical of a false claim the first time it floats through our Twitter timeline, but the more we are exposed to it, the more we start to feel like it’s true—and our pre-existing knowledge does little to prevent this.

Systemic effects

In our age of social media, it’s incredibly easy for misinformation to spread quickly to huge numbers of people. The evidence suggests that global politics have already been strongly influenced by online propaganda campaigns, run by bad actors who understand that all they need to do to help a lie gain traction is to repeat it again and again. Now more than ever, it is important to be wary of the fact that the way we assess the accuracy of information is biased.

How it affects product

Advertisers might take advantage of the illusory truth effect by repeating messages across different platforms and mediums. Even if a consumer initially doubts the validity of a claim, repeated exposure can make it feel more truthful. For instance, if a fitness app repeatedly claims it's "the most effective workout app," users may start to believe it simply because they've seen the claim so many times before.

The illusory truth effect and AI

Just like with any popular trend, if there's constant buzz around a particular AI model or technique and it's repeatedly presented as the "best" solution, people might default to using it—even in situations where it might not be the most appropriate choice.

On the flip side, if there are repeated negative claims about a new AI technology—whether they're true or not—people might become resistant to adopting it. For instance, if there's constant news about how a particular AI-driven innovation "isn't ready yet" or "has too many flaws," the broader public might start believing these statements and be hesitant to engage with the technology, even if it improves over time.

Why it happens

How do we gauge whether a claim is true or false? Naturally, you might assume we use our existing base of knowledge, and maybe a couple of well-placed Google searches, to compare a claim to available evidence. No rational person would accept a statement as true without first holding it up to the light and critically examining it, right?

Unfortunately, humans are rarely rational beings. Every single day, we make an average of 35,000 decisions.19 With all of those choices to make, and the huge volume of information coming at us every second, we can’t possibly hope to process everything as deeply as we might like.

To conserve our limited mental energy, we rely on countless shortcuts, known as heuristics, to make sense of the world. This strategy can often lead us to make errors in our judgment. Here are a few fundamental heuristics and biases that underlie the illusory truth effect.

We are often cognitively lazy

According to the renowned behavioral economist Daniel Kahneman, there are two thinking systems in our brains: System 1 and System 2. System 1 is fast and automatic, working without our conscious awareness; meanwhile, System 2 handles deeper, more effortful processing, and is under our conscious control.1 Since it’s doing the harder work, System 2 drains more of our cognitive resources; it’s effortful and straining to engage, which we don’t like. So, whenever possible, we prefer to rely on System 1 (even if we don’t realize that’s what we’re doing).

This preference for easy processing (also known as processing fluency) is more deeply rooted than many of us realize. In one experiment, participants were shown images on a screen while researchers measured the movements of their facial muscles. Some of the images were made easier to process by having their outlines appear before the rest of the picture—only by a fraction of a second, so briefly that participants didn’t consciously realize it was happening. Still, when processing was made easier in this way, people’s brows relaxed, and they even smiled slightly.1 Processing fluency even has implications in the business world: stocks with pronounceable trading names (for example, KAR) consistently do better than unpronounceable ones (such as PXG).

The problem with processing fluency is that it can influence our judgments about the accuracy of a claim. If it’s relatively effortless to process a piece of information, it makes us feel like it must be accurate. Consider another experiment, where participants were given problems that were deliberately designed to trip people up. For example:

If it takes 5 machines 5 minutes to make 5 widgets, how long would it take 100 machines to make 100 widgets?

100 minutes OR 5 minutes

Most of us, when we read this problem, intuitively want to say 100 minutes—but it’s actually 5. For some of the participants in this study, researchers made the questions more difficult to read, by presenting them in a barely-legible, small, gray font. When they did this, participants actually performed better—because they had to engage their more effortful System 2 thinking to parse the question. Meanwhile, when the problems were written in a normal, easy-to-read font, people were more likely to go with their (incorrect) intuition.1

Familiarity making processing easy

What does processing fluency have to do with the illusory truth effect? The answer lies with familiarity. When we’re repeatedly exposed to the same information—even if it’s meaningless, or if we aren’t consciously aware that we’ve seen it before—it gradually becomes easier for us to process. And as we’ve seen, the less effort we have to expend to process something, the more positively we feel about that thing. This gives rise to the mere exposure effect, which describes how people feel more positively about things they’ve encountered before, even very briefly.

In a classic experiment illustrating the mere exposure effect, Robert Zajonc took out ads in student newspapers at two Michigan universities over a period of a few weeks. Every day, the front page of each paper featured one or more Turkish words. Some words appeared more frequently than others, and the frequency of each word was also reversed between the two papers, so that the most-frequently appearing word in one paper would be the least-frequently appearing one in the other.

After the exposure period was over, Zajonc sent out a questionnaire to both communities, asking respondents to give their impressions of 12 “unfamiliar” words. Some of the words were the Turkish words that had run in the newspapers. Participants rated each word from 1 to 7 based on whether they thought the word meant something “good” or “bad.” The results showed that, the more frequently participants had been exposed to a given word, the more positively they felt about it.1,2

For a long time, psychologists (reasonably) believed that ease of processing was only important in situations where we lack knowledge about something—that we use it as sort of a last-ditch attempt to come to a conclusion. Unfortunately, the evidence suggests that things might work the other way around: ease of processing is our go-to tool to judge whether something is true, and it’s only if that fails that we turn to our knowledge for help. One study found that college students fell for the illusory truth effect even when a subsequent knowledge test showed that they knew the correct answer.3 This phenomenon is known as knowledge neglect: even though people knew the right answers, they could still be led astray by the illusory truth effect.

Why it is important

By now, most of us are all too familiar with the phrase “fake news.” The internet is a breeding ground for false rumors, conspiracy theories, and outright lies, and none of us are immune. According to a study published in the journal Science, on average, false stories reach 1,500 people six times faster than true stories do.4,5 They’re also 70 percent more likely to be retweeted than real stories. Our media ecosystem is so awash in falsehoods, it’s inevitable that all of us will encounter fake news at some point—and in fact, we probably do so on a very regular basis. This alone puts us at risk of the illusory truth effect.

The illusory truth effect doesn’t just affect us by accident, either. Propagandists understand that repetition is key to getting people to accept your message, even if they don’t believe it at first. Even Adolf Hitler wrote in Mein Kampf that “slogans should be persistently repeated until the very last individual has come to grasp the idea.”8 When politicians repeat obvious untruths again, and again, and again, we should not just roll our eyes and write it off as a blunder. We should recognize that this is a deliberate strategy, aiming to familiarize people with the lie being told until they accept that lie as truth.

This all might be sounding a little overly dramatic, but this worry is warranted. Misinformation poses a sinister threat to democracy and the functioning of civil society in general. Around the world, fake news has fueled acts of violence. For example, in 2018, rumors spread on WhatsApp sparked a mob killing in India.6 As the coronavirus pandemic spreads across the globe, conspiracy theories have driven large crowds of protesters to march in opposition to social distancing and mask regulations.9

While it’s true that bots are behind the spread of a lot of false stories, studies show the lion’s share of the blame lies with real humans.5 And yet, even as we propagate misinformation, most of us are anxious about the effects of fake news. A Pew Research poll found that 64% of American adults believe that fake news stories cause a “great deal of confusion.”7

Clearly, the problem is not a lack of awareness: people know that unreliable information circulates online. It seems that they just don’t think that they would ever fall for those stories. It’s important to be aware of the illusory truth effect and other biases that affect our judgment so that we are motivated to pause and think a bit more critically about information we might otherwise accept as true.

How to avoid it

The illusory truth effect is tricky to avoid. Because it is driven by System 1, our unconscious and automatic processing system, we usually don’t realize when we’ve fallen prey to it. It’s also a very pervasive bias: research has shown that people are equally susceptible to the illusory truth effect, regardless of their particular style of thinking.10 That said, by making a deliberate and concerted effort to be critical of the claims we encounter, it is possible to get around this effect.

“Critical thinking” might seem like a boring, obvious answer to this problem, but it’s the best solution to avoid falling for the illusory truth effect. With such massive amounts of information filtering past our eyeballs every day, it’s easy to let suspicious claims slide and just move onto the next tweet or status update. But by neglecting to think critically the first time we encounter a false statement, we make ourselves more susceptible to the illusory truth effect.

In one study, participants were asked to read a list of widely-known facts, with a few falsehoods mixed in. One group of participants rated how true they thought each claim was, while the other rated how interesting they were. Later, both groups saw the same statements again, and rated how true they thought they were. The researchers found that, when participants had initially been asked to evaluate truthfulness instead of interestingness, they didn’t show signs of the illusory truth effect—but only when they had relevant knowledge about the statements.11

In short, fact-checking claims the first time you hear them is important to reduce the power of the illusory truth effect. Google is your friend, and when it comes to lies that have political implications, websites like Politifact and Snopes are constantly working to fact-check and debunk fake news. Also try to train yourself to be aware of red flags that you might be reading bad intel. These include things like vague or untraceable sources, poor spelling and grammar, and stories that seem like they would be huge scoops yet aren’t being reported on by any mainstream sources.12

How it all started

The illusory truth effect was first discussed in a 1977 paper by Lynn Hasher, David Goldstein, and Thomas Toppino. The three researchers had college students come into the lab on three separate occasions, each visit two weeks apart, to read a list of statements (both true and false) and rate how accurate they believed each of them was. Over the three sessions, participants rated both true and false statements as progressively more accurate.13

Hasher, Goldstien, and Toppino’s work was the first to demonstrate the power of repetition on belief. However, it’s important to note that, in this study, the statements being judged were “plausible but unlikely to be specifically known by most college students.” Most of the participants in this original experiment probably didn’t have any relevant knowledge, and were more or less flying blind when they were asked to judge the accuracy of each statement for the first time. Later studies would go on to demonstrate that the illusory truth effect occurred even when people did have knowledge about the claims they were evaluating.

Interest in the illusory truth effect grew in the late 2000s and 2010s, as the internet and social media became more and more important for disseminating information. It became a particularly popular research topic after the 2016 U.S. presidential election, when questions were swirling about the influence of foreign disinformation campaigns. Research showed that the illusory truth effect likely played a role in people’s acceptance of blatantly false stories on social media.14

Example 1 – The body temperature of a chicken…

One famous example of the illusory truth effect shows that we only need to have encountered part of a statement in order for this bias to kick in. In Thinking, Fast and Slow, Kahneman writes that when people were repeatedly exposed to the phrase “the body temperature of a chicken”—an incomplete sentence that doesn’t actually make any claims—they were more likely to believe the statement that “the body temperature of a chicken is 144°” (or any other arbitrary number).1 Apparently, partial familiarity is familiar enough.

Example 2 – COVID and hydroxychloroquine

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, the search for effective treatments and preventative measures was at the front of everyone’s mind, politicians and citizens alike. Given the considerable political benefits that would come with finding a cure, it’s not surprising that elected officials were especially keen to talk up promising new drugs.

But the strategy adopted by Donald Trump and his campaign—to repeatedly tout the benefits of a specific drug, hydroxychloroquine, before it was clinically proven—looked like an attempt to capitalize on the illusory truth effect. For months, Trump endlessly sung the praises of hydroxychloroquine, prompting tens of thousands of patients to request prescriptions from their doctors.15 Even now, with clinical trials showing that the drug is not effective to treat COVID-19,16 the belief that it works is still widespread. Trump’s claims were also repeated by public figures like Dr. Oz, increasing people’s exposure to them as well as giving them a veneer of legitimacy (Oz is an actual medical doctor).17

Summary

What is it

The illusory truth effect describes how, when we are repeatedly exposed to misinformation, we are more likely to believe that it’s true.

Why it happens

The main reason for the illusory truth effect is processing fluency: when something is easy to process (as familiar information is), we tend to assume that means it is accurate.

Example 1 – The body temperature of a chicken…

When people had previously been exposed to the incomplete sentence “the body temperature of a chicken,” they were more likely to endorse any completed version of this statement, filled in with an arbitrary number.

Example 2 – Illusory truth and hydroxychloroquine

In the early months of the global coronavirus pandemic, US president Donald Trump frequently talked about the drug hydroxychloroquine as a potential cure for COVID-19. These claims were repeated so often that many people continue to believe them, even after clinical evidence has contradicted them.

How to avoid it

Critical thinking and fact-checking are the best lines of defense against the illusory truth effect.

Related TDL articles

Fake News: Why Does it Persist and Who’s Sharing it?

This article is an in-depth look at the phenomenon of fake news: where most of it is coming from, why it spreads so easily, and how the illusory truth effect plays a role.

How to Fight Fake News With Behavioral Science

This piece explores how we can leverage behavioral science to fight the spread of fake news, including some simple strategies that anybody can use to help protect themselves from misinformation.