Why do we blame external factors for our own mistakes?

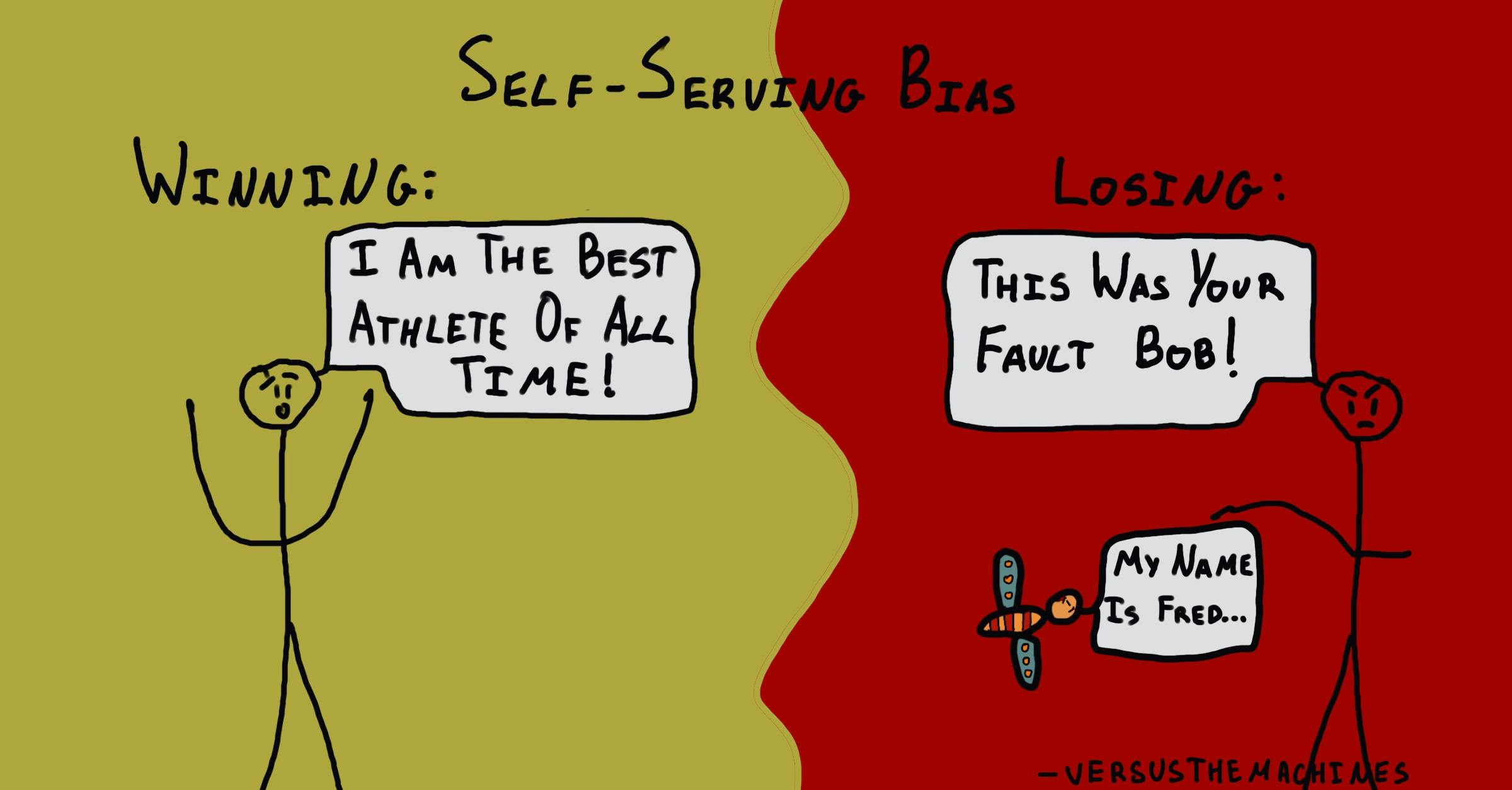

Self-serving Bias

, explained.What is the Self-Serving Bias?

The self-serving bias describes when we attribute positive events and successes to our own character or actions but blame negative results on external factors unrelated to our character. The self-serving bias is a common cognitive bias that is often compared to the fundamental attribution error.1

Where this bias occurs

Many of us will remember the feelings associated with getting a good grade versus a bad grade in school. Particularly as younger students, we can remember being proud of ourselves for getting good grades. Attributing our success to our own skills and hard work. On the other hand, if we were to receive a poor grade, we may attribute the result to external factors. These external factors could range from things such as a professor’s inability to teach the subject, the difficulty of the topic, or our group members.

This process is common among many of us, as our initial reaction is to praise ourselves when we achieve success and blame external factors for our shortcomings. This seemingly harmless habit can have significant implications on our life as we age, hence the importance of identifying and curtailing behavior related to it.

Debias Your Organization

Most of us work & live in environments that aren’t optimized for solid decision-making. We work with organizations of all kinds to identify sources of cognitive bias & develop tailored solutions.

Related Biases

Individual effects

Being aware of the self-serving bias and its impact on our lives is essential because it changes how we learn from our mistakes, and it can affect our decision-making. Overall, the self-serving bias is problematic: If we do not attribute our failures to our own errors, we are unlikely to learn from them in the future. Furthermore, refusing to acknowledge our mistakes makes us susceptible to repeating them down the line. Failing and learning from our failures is essential to becoming successful, achieving our goals and fulfilling our ambitions. If an individual cannot attribute their failures to mistakes they made themselves, then improvement is a difficult and unlikely process.

Systemic effects

The self-serving bias has a cumulative effect when looking at societies and nations as a whole. Take climate change as an example: a study conducted by researchers at Carnegie Mellon University looked at climate policy and citizens’ perceptions on which country should make an effort to lower its emissions. By conducting surveys among college students in both China and the United States, the researchers noted that each group of students held self-serving biases in regard to the economic burdens that would result from mitigating climate change and reducing greenhouse gas emissions in their own country.2

Their research confirms that the self-serving bias does, in fact, play a role in explaining why it is difficult for various nations to come to an agreement on their responsibility in emission reduction strategies. Researchers noted that interventions that aim to mitigate self-serving biases may facilitate agreement in environmental policy discussions, both at the national and international levels.2 The self-serving bias can influence other policy decisions at all levels of government. Reducing cognitive biases in policymakers and government officials is necessary to ensure policy decisions are based on facts and better improve the populations they serve.

How it affects product

The self-serving bias can lead to both poorly planned products and slow, unhelpful customer service.

If a product doesn't perform well on the market, teams might blame it on external factors such as market conditions, competitors, or even the marketing team rather than accept that the product itself has shortcomings. This can lead to a waste of time and money. It can also impact how well the team works together.

Not only does the self-serving bias make us resistant to negative feedback, but it leads us to be defensive when we receive criticism. In the event that a customer is displeased with a product, a primary instinct may be to defend the project or pin the blame on the user for incorrect use. However, this can translate to further customer dissatisfaction and a missed opportunity for redemption.

The self-serving bias and AI

While the integration of AI has sped up the process of innovation, we often lack accountability systems for when AI fails. If a system fails or produces incorrect outputs, those involved might be quick to blame external factors, such as insufficient data or unpredictable market conditions, rather than acknowledging that the AI system (or their use of it) might have had inherent flaws.

Why it happens

The self-serving bias is a common fallacy and is described as a distorted perceptual process.3 Researchers have identified several different reasons why the self-serving bias occurs so frequently among individuals.

Self-Esteem

The self-serving bias serves as a maintenance or enhancement mechanism for our self-esteem.3 By attributing our successes to our own characteristics and our failures to external circumstances, we spare ourselves any real opportunity for criticism. The self-serving bias skews our perception of ourselves and our reality, improving and preserving our self-esteem.

Self-Presentation

Self-presentation describes how an individual conveys information about themselves to others. Self-presentation can be used to match an individual’s self-image to others or try to match audience expectations and preferences.4

Self-presentation aids individuals in maintaining their self-esteem, as they are affected by how others perceive them. To continue to enhance their self-esteem, an individual actively portrays favorable impressions of themselves to others.5

Natural Optimism

Another reason that this cognitive bias is particularly common is due to the fact that humans are inherently optimistic. Negative outcomes tend to surprise people, and thus, we are more likely to attribute negative results or outcomes to situational and external factors rather than personal reasons. Along with our gravitation to optimism, humans consistently make fundamental attribution errors. The fundamental attribution error describes how when others around us make mistakes, we blame the individual who makes the error, but when we make mistakes ourselves, we blame circumstances for our failures.6

Age & Culture

The Self-serving bias does vary when looking at different age groups and cultures. Researchers have confirmed that self-serving bias is most prevalent among young children and older adults. From a cultural perspective, there is no official consensus regarding self-serving biases and cross-culture influences. However, researchers globally are now further investigating the cultural implications of self-serving bias, specifically in regard to differences demonstrated in Western and Eastern cultures.7

Why it is important

The self-serving bias can affect many important aspects of our life. Commonly, self-serving bias can affect our performance throughout school, in our careers, in sports, and impacts our interpersonal relationships. Being aware of what causes the successes and failures in our lives, both personal and professional, can provide us with learning opportunities to improve. Understanding the self-serving bias, how it appears in our life, and how we can avoid it to make better choices and decisions is essential to continue improving ourselves and our situations.

How to avoid it

Though self-serving bias is common, there are many ways to avoid it and prevent it from impairing our day-to-day decisions. Mindful awareness helps us first recognize our susceptibility to self-serving bias when it occurs. When an individual learns about common cognitive biases, they can begin to notice them, specifically in their lives, providing an opportunity to self-correct.

Our ability to be self-compassionate is another way to help mitigate self-serving bias. When we are self-compassionate, we can reduce our defensiveness and better take criticism when looking to self-improve. Self-compassion is an individual’s ability to recognize distress and commit to alleviating that distress. Self-compassion involves the following components.8

- An individual’s ability to demonstrate self-kindness, especially when experiencing a sort of personal failure.

- An individual’s ability to understand their common humanity, or rather, that they are human and that other humans experience the same sort of experiences and failures.

- Finally, an individual’s mindfulness and being able to identify uncomfortable thoughts without judging them.

Being less critical, and more open to improvement through self-compassion is especially helpful for athletes. In sports, self-compassion has correlated with having fewer negative thoughts and feelings9 and aiding athletes in reducing self-criticism and negative thoughts after making mistakes.10

Additionally, athletes who are self-compassionate can better improve and take constructive criticism, as self-compassion provides them with the ability to create realistic self-evaluations about their performance without the fear of recognizing their weaknesses, and lowering their self-esteem.8

How it all started

The self-serving bias first became a notable phenomenon by the end of the 1960s. The theory was first developed through research conducted in parallel to the attribution bias, a cognitive bias that refers to the many systematic errors people make when evaluating reasons for others and their behavior.11 During this research, an Austrian psychologist named Fritz Heider found that in ambiguous scenarios, people tend to make attributions based on their own needs in order to maintain a higher level of self-esteem for themselves, defining it as the self-serving bias.

Today, the self-serving bias is researched in several capacities. Laboratory testing, neural experimentation, and naturalistic investigation are all used to investigate this cognitive bias, its relation to different fields, and ways to mitigate it. Modern research regarding the self-serving bias has begun focusing on physiological manipulations in order to better understand the biological mechanism that contributes to the self-serving bias.12,13

Additionally, substantial research has been conducted to study depression and self-serving bias. Clinically depressed individuals show less self-serving bias than the average person. People diagnosed with depression are more likely to attribute negative outcomes to their internal faults and characteristics while attributing successes to external factors and luck.4 Research in self-serving bias has aided in identifying negative emotions in clinically depressed individuals alongside their self-focused attention, which leads to their lack of exhibiting self-serving bias.14

Example 1 - Self-serving bias in the workplace

The workplace provides many examples of self-serving bias. Specifically, research on work-related self-serving bias identified that the effect was most present in relation to negative outcomes and that the more distant the relationship between employees and their colleagues was, the more coworkers blamed each other for failure in the workplace.16

Self-serving bias is also commonly found in relation to explaining both employment and termination of one’s job. People were found to typically attribute their personal characteristics to the reasons that they were hired and blamed external factors for their own termination from their jobs.17

Example 2 - Self-serving bias in sports

Examples of self-serving bias are also particularly common in regard to sports, such as when athletes evaluate the outcomes of sporting events. Individual sports especially tend to showcase self-serving bias, likely because one-on-one sports have clearly defined winners, and the results of a match can be more easily attributed to one’s action than a team sport, where the entire group is recognized.18

A study conducted on Division I collegiate wrestlers tested the self-serving bias. The wrestlers were asked to self-report their performance from their preseason matches and the results of these matches. It was found that wrestlers who won were more likely to attribute their success to internal and personal causes than those who lost.18

Another study in 1987 looked to compare self-serving biases between individual sports athletes and team sports athletes. The study gathered 549 statements from athletes who played tennis, golf, baseball, football and basketball and concluded that individual sport athletes made more self-serving attributions than sports team athletes.19 This research concludes that individual sports athletes and their performance during sporting games significantly affected their self-esteem, thus using the self-serving bias to increase their confidence.19

Summary

What it is

The self-serving bias refers to an individual’s tendency to attribute positive events to their character, but attribute negative results or events to external factors unrelated to themselves and their faults.

Why it happens

The self-serving bias is a distorted cognitive process and is typical for a multitude of reasons. Several reasons that one may be susceptible to the self-serving bias include an individual’s need to improve their self-esteem, the natural optimism humans possess, or an individual’s age or cultural background.

Example #1 – Self-serving bias in the workplace

Examples of the self-serving bias are commonly found in the workforce, with instances of self-serving biases being seen in one’s perception of why they were hired, fired, received a bonus, or performed poorly. People were found to typically attribute their personal characteristics to reasons that they were hired and blamed external factors for their own termination from their job.

Example #2 – Self-serving bias in sports

Sports players are commonly cited when looking at examples of self-serving biases, especially those who compete in individual sports. Studies conducted on high-level wrestlers found that those who won attributed their wins to internal characteristics, while those who lost typically attributed their wins to external factors.

How to avoid it

The best way to avoid the self-serving bias is to be aware of what the self-serving bias is, and identify how you could possibly be using it in your own life. Mindfulness provides an opportunity to find solutions to overcome this bias. Additionally, being open to criticism and being self-compassionate is a potential way to avoid the self-serving bias.