Unlocking Educational Outcomes with Behavioral Insights

0 min read

Inequality has always been present in the U.S. education system. Though progress has been made over the past few decades, achievement gaps persist in American classrooms. Time and time again, research shows that racialized students, low-income students, and students who speak English as a second language tend to have worse learning outcomes.

One major contributor to these achievement gaps is unequal access to high quality learning materials, such as textbooks and educational technology (EdTech). Quality materials are a key contributor to both college and career readiness, even when other factors such as teacher quality are controlled for. But the quality of the curricula that schools use in their classrooms varies widely from district to district, with Black, Latino, and low-income students bearing the brunt of these disparities.

In large part, this problem comes down to decision-making. School district leaders who are responsible for making decisions about which materials to purchase often fail to differentiate between options that are best suited to their students and those that aren’t. This is largely due to the noisy choice environment for instructional materials. School districts are faced with a vast number of different learning materials to choose from – and there aren’t always clear markers of quality. Many districts may simply choose the instructional materials that are the most convenient, or materials that were recommended to them by a friend.

Designing better evidence

In an effort to create an informational environment conducive to evidenced-based purchases, a vast ecosystem of resources has been developed by researchers, educational non-profits, and others to help school district purchasers sift through all the noise. But historically, evidence creators haven’t fully accounted for decision-making contexts, or the biases and heuristics that inform ultimate evidence use. As a result, the information they’re trying to convey isn’t always laid out in a way that’s easily understood by purchasers.

On the other side, decision-makers who engage with this evidence have been influenced by negative instances of evidence “overselling” results or being inapplicable to their district contexts.

In short, the available evidence on learning material quality isn’t as impactful as it could be. This means that students in priority districts are still less likely to have high-quality, standards-aligned learning materials, despite an abundance of resources that could help their district officials close those gaps.

Charting a way forward

In a previous project with The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, TDL became the first research organization to map out the purchasing journeys for instructional materials. Now we wanted to know more about how those stakeholders were — or weren’t — using the evidence available to them in order to make those decisions.

With support from The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, TDL partnered with EdReports and the International Society Technology in Education (ISTE), two leading voices on instructional material quality: The key goal was to study how districts are engaging with evidence with making purchasing decisions in order to provide evidence aligned with their needs. Key research questions included: How do districts incorporate evidence into their decisions? Which types of information are most readily used? And how can evidence creators optimize their information to maximize the educational outcomes for students? We wanted to make evidence more usable and actionable, to promote high-quality purchasing decisions across districts.

Diagnosing the problem

In our research, we worked with more than 500 core and supplemental instructional materials district purchasers. We began by conducting extensive user research on instructional material purchasing on both the demand (district) and supply (edtech vendor) sides. We engaged EdTech vendors in order to map the EdTech development process and assess how they engage with evidence. To study demand-side dynamics of EdTech and curriculum, we recruited K-12 purchasers, collecting hundreds of interviews and surveys.

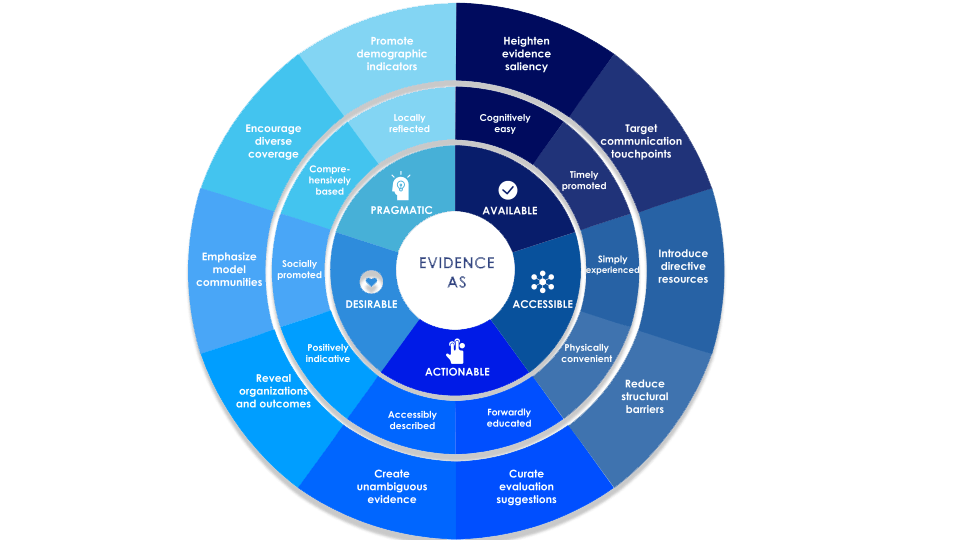

Our research revealed 5 key drivers to evidence uptake amongst district purchasers:

- Availability: Information should be intuitive to find.

- Accessibility: Information should be frictionless to obtain.

- Actionability: Information should be presented with implementation in mind.

- Desirability: Information should be framed as a useful and rewarding source to leverage.

- Pragmatism: Information should speak to real users and real outcomes.

These findings, in conjunction with relevant behavioral levers and frameworks, became the foundation of the Evidence Uptake Framework.

This model is designed to work as a guide for evidence creators (meaning anybody producing resources to help guide purchasing decisions). It lays out the 5 key drivers and breaks them down into specific recommendations that creators can use to boost the impact of their work.

Going public

But our project didn’t end with the evidence uptake framework. We’re still in the process of building this toolkit out into a publicly accessible online platform. When it’s launched, this tool will act as a behavioral change hub for evidence creators: with a few clicks, users can find evidence-based strategies for crafting resources that resonate with school decision-makers. They can also filter depending on their specific goals and primary audiences, from curriculum school staff and district administrators to EdTech vendors.

Equitable learning for all

The purchasing experience can be complex and confusing for district purchasers — but students shouldn’t be the ones caught in the crosshairs. Our work with EdReports and ISTE will help to ensure that every student has the opportunity to learn from the best educational materials available.